Compact Muon Solenoid

LHC, CERN

| CMS-EXO-23-016 ; CERN-EP-2025-282 | ||

| Strategy and performance of the CMS long-lived particle trigger program in proton-proton collisions at $ \sqrt{s}= $ 13.6 TeV | ||

| CMS Collaboration | ||

| 24 January 2026 | ||

| Submitted to Physics Reports | ||

| Abstract: In the physics program of the CMS experiment during the CERN LHC Run 3, which started in 2022, the long-lived particle triggers have been improved and extended to expand the scope of the corresponding searches. These dedicated triggers and their performance are described in this paper, using several theoretical benchmark models that extend the standard model of particle physics. The results are based on proton-proton collision data collected with the CMS detector during 2022--2024 at a center-of-mass energy of 13.6 TeV, corresponding to integrated luminosities of up to 123 fb$ ^{-1} $. | ||

| Links: e-print arXiv:2601.17544 [hep-ex] (PDF) ; CDS record ; inSPIRE record ; CADI line (restricted) ; | ||

| Figures | |

png pdf |

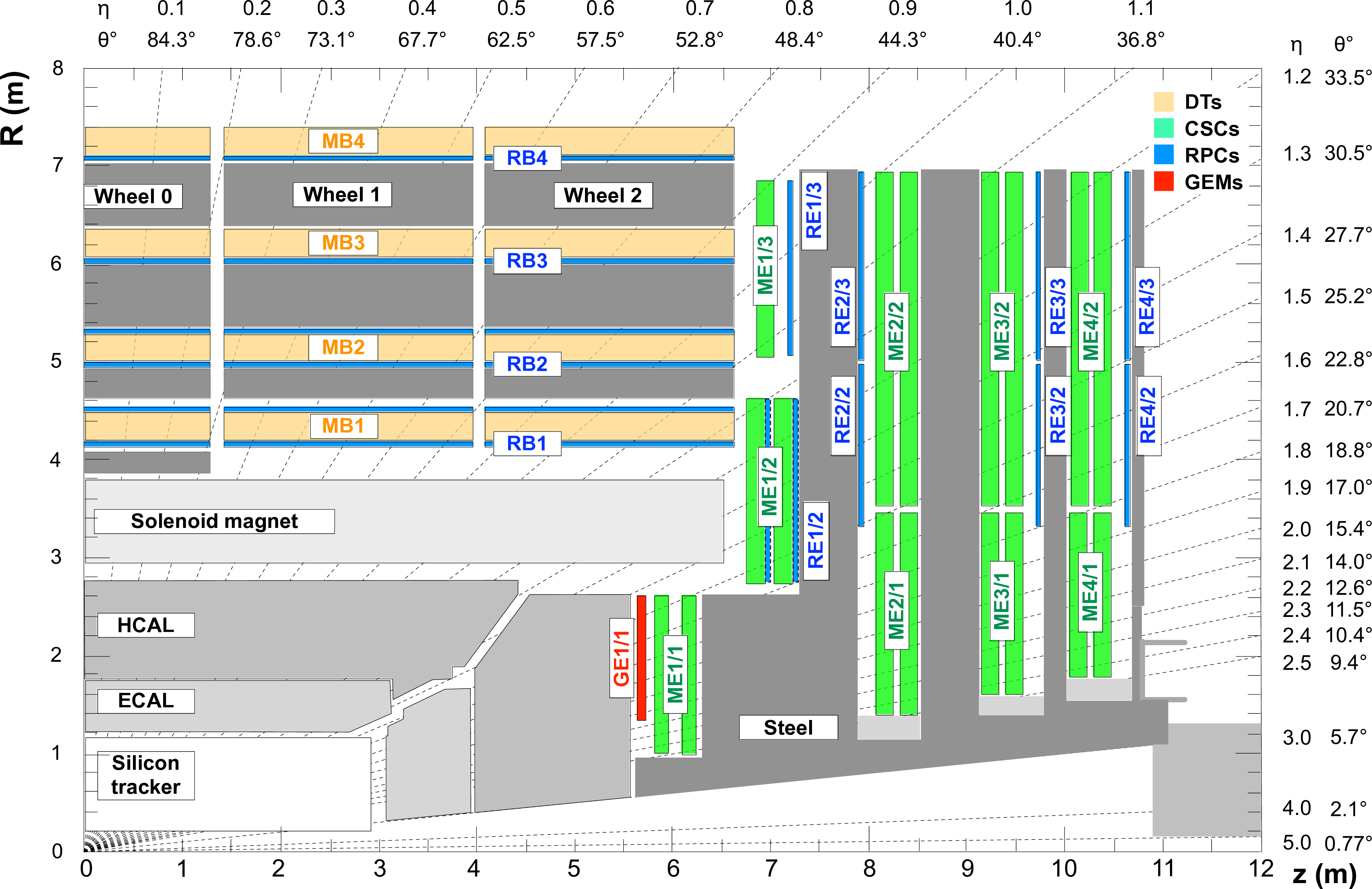

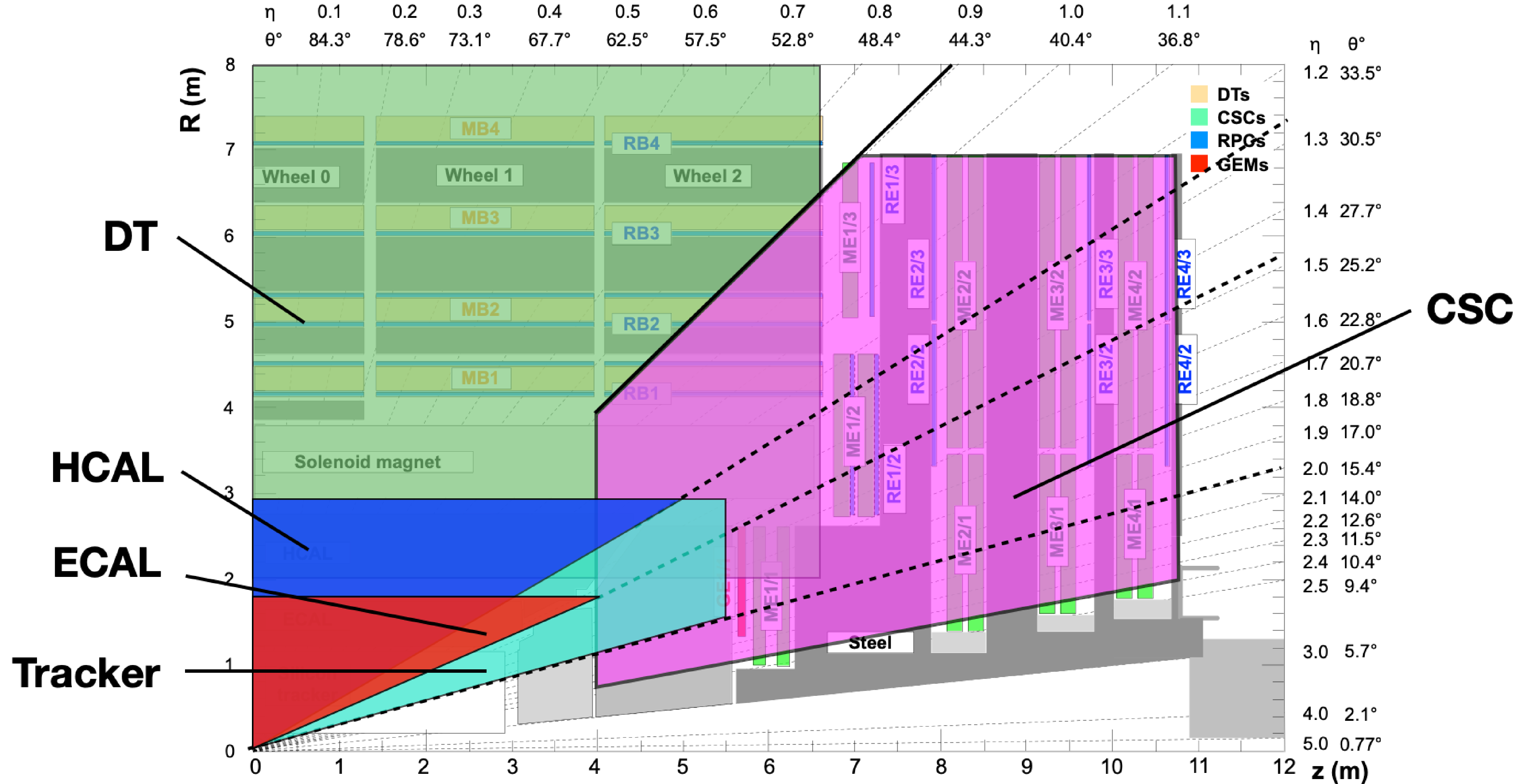

Figure 1:

Schematic view in the $ R-z $ plane of a CMS detector quadrant at the start of Run 3, with the axis parallel to the beam ($ z $) running horizontally and the radius ($ R $) increasing upward. The nominal interaction point (IP) is in the lower left corner. The locations of the various muon detectors and the steel flux-return yoke (dark areas) are shown, along with the silicon tracker, the electromagnetic calorimeter (ECAL), and the hadronic calorimeter (HCAL). The locations of the various muon detectors are shown in color: drift tubes (DTs) with labels MB, cathode strip chambers (CSCs) with labels ME, resistive plate chambers (RPCs) with labels RB and RE, and gas electron multipliers (GEMs) with labels GE. The M denotes muon, B stands for barrel, and E for endcap. Figure taken from Ref. [24]. |

png pdf |

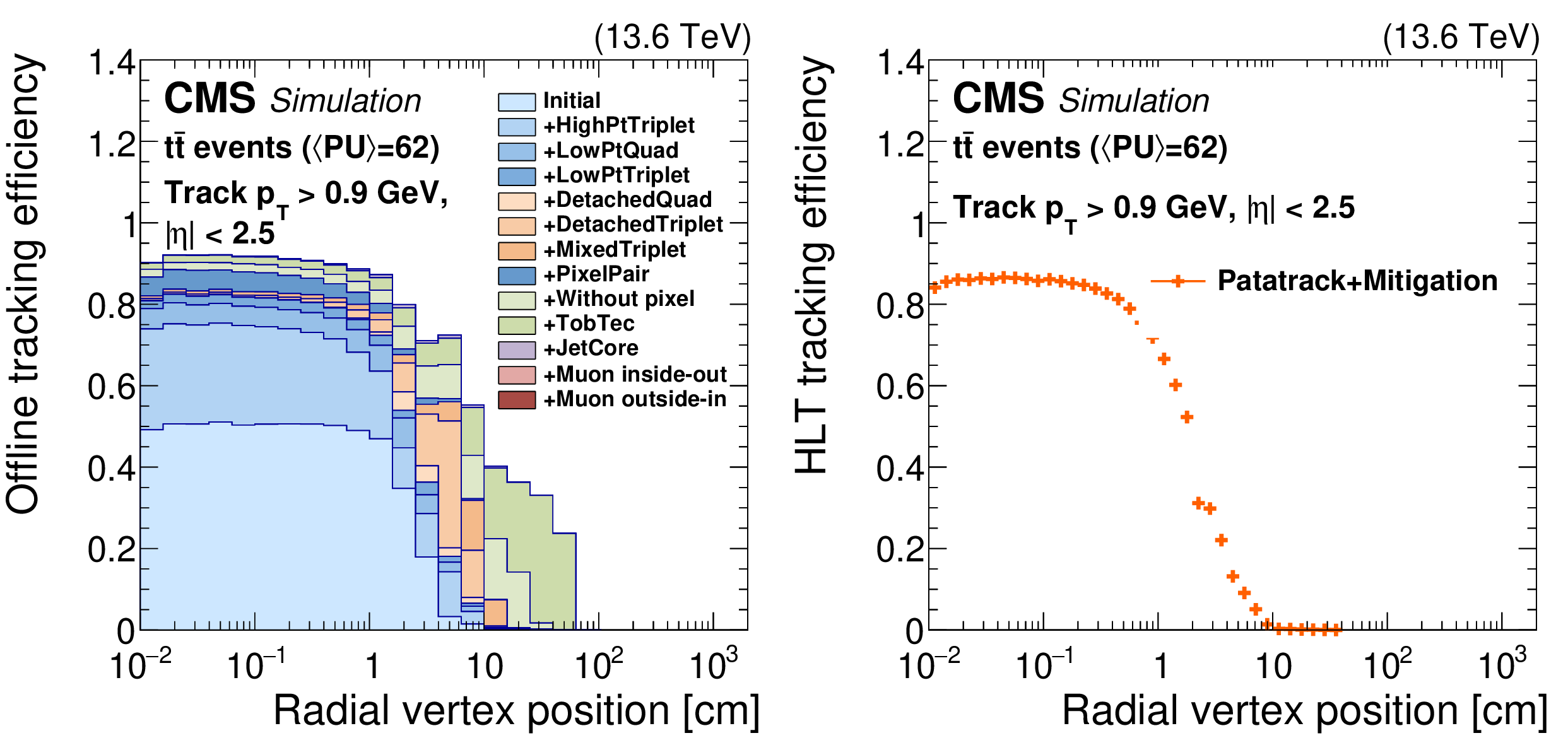

Figure 2:

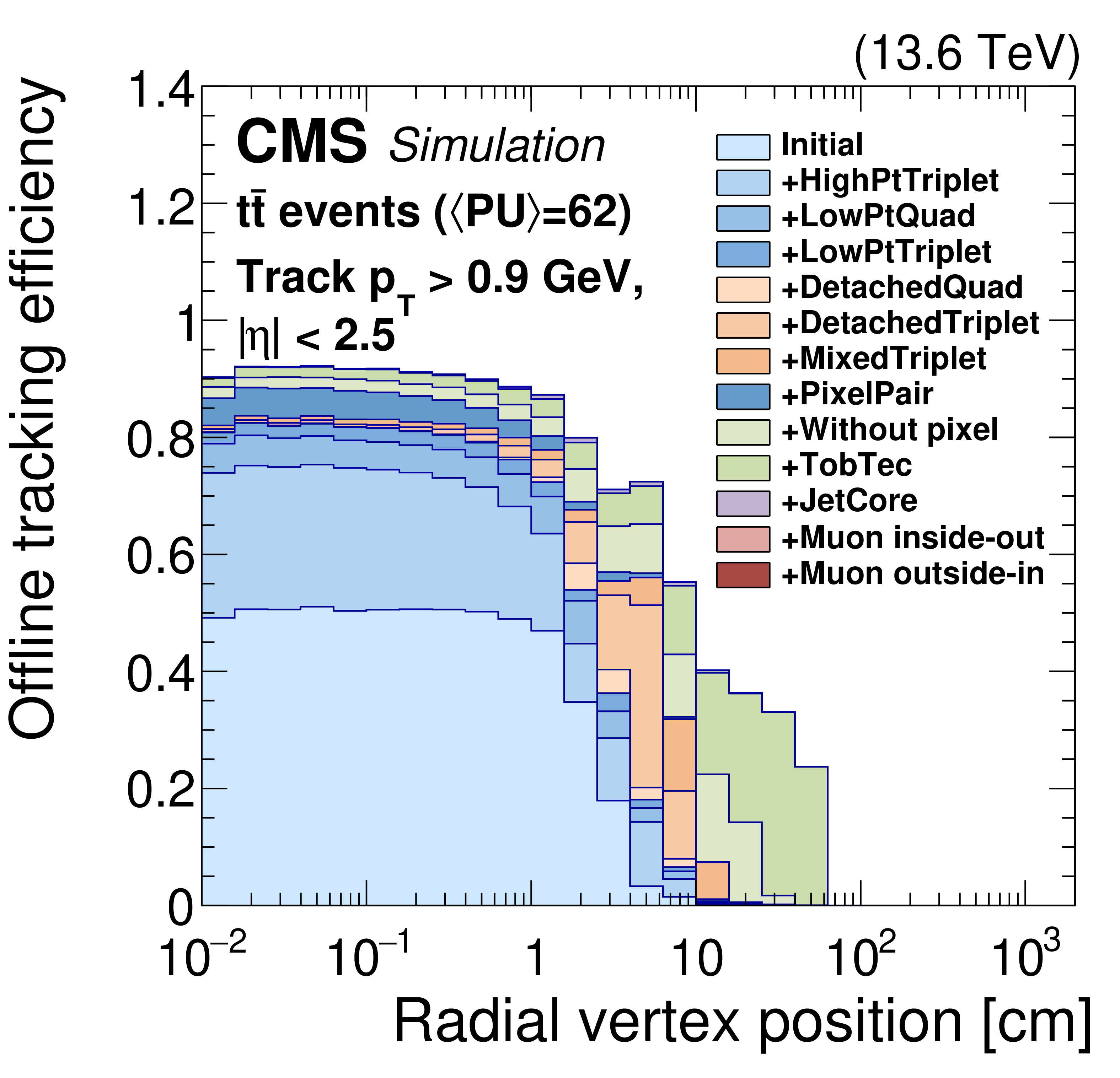

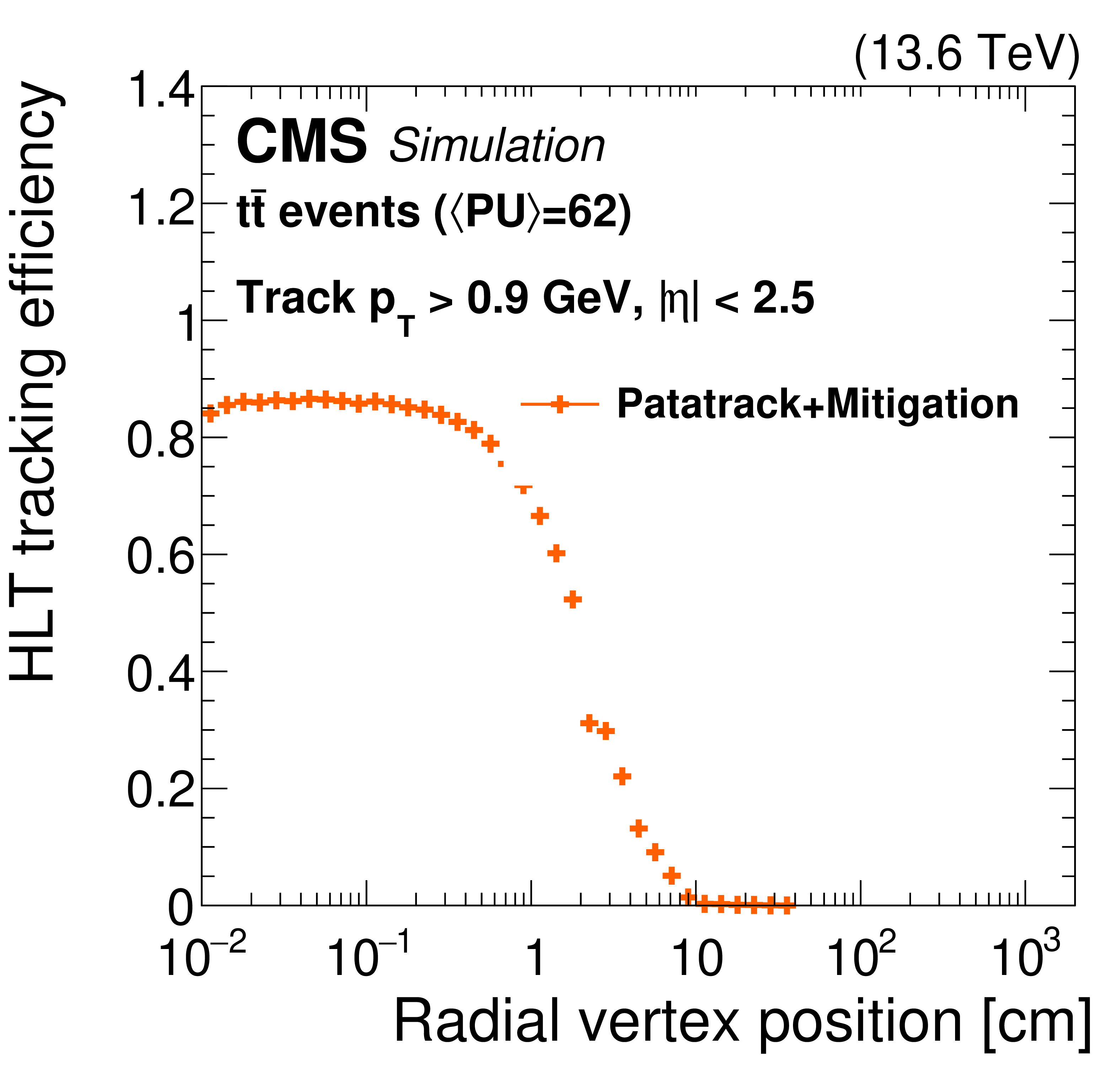

The offline standard tracking efficiency during Run 3 (left) for different tracking iterations, as a function of simulated radial position of the track production vertex. The overall standard tracking efficiency at the HLT during Run 3 (right), as a function of the simulated radial position of the track production vertex. The standard tracking at the HLT includes the nominal PATATRACK global iteration plus the additional iteration that mitigates the pixel detector issues. For both plots, a $ \mathrm{t} \overline{\mathrm{t}} $ simulation under 2025 conditions with an average PU of 62 is used, and the tracks are required to have $ p_{\mathrm{T}} > $ 0.9 GeV and $ |\eta| < $ 2.5. The tracking efficiency is defined as the number of simulated tracks (with the aforementioned selection requirements) geometrically matched to a reconstructed track, divided by the total simulated tracks passing the selections. |

png pdf |

Figure 2-a:

The offline standard tracking efficiency during Run 3 (left) for different tracking iterations, as a function of simulated radial position of the track production vertex. The overall standard tracking efficiency at the HLT during Run 3 (right), as a function of the simulated radial position of the track production vertex. The standard tracking at the HLT includes the nominal PATATRACK global iteration plus the additional iteration that mitigates the pixel detector issues. For both plots, a $ \mathrm{t} \overline{\mathrm{t}} $ simulation under 2025 conditions with an average PU of 62 is used, and the tracks are required to have $ p_{\mathrm{T}} > $ 0.9 GeV and $ |\eta| < $ 2.5. The tracking efficiency is defined as the number of simulated tracks (with the aforementioned selection requirements) geometrically matched to a reconstructed track, divided by the total simulated tracks passing the selections. |

png pdf |

Figure 2-b:

The offline standard tracking efficiency during Run 3 (left) for different tracking iterations, as a function of simulated radial position of the track production vertex. The overall standard tracking efficiency at the HLT during Run 3 (right), as a function of the simulated radial position of the track production vertex. The standard tracking at the HLT includes the nominal PATATRACK global iteration plus the additional iteration that mitigates the pixel detector issues. For both plots, a $ \mathrm{t} \overline{\mathrm{t}} $ simulation under 2025 conditions with an average PU of 62 is used, and the tracks are required to have $ p_{\mathrm{T}} > $ 0.9 GeV and $ |\eta| < $ 2.5. The tracking efficiency is defined as the number of simulated tracks (with the aforementioned selection requirements) geometrically matched to a reconstructed track, divided by the total simulated tracks passing the selections. |

png pdf |

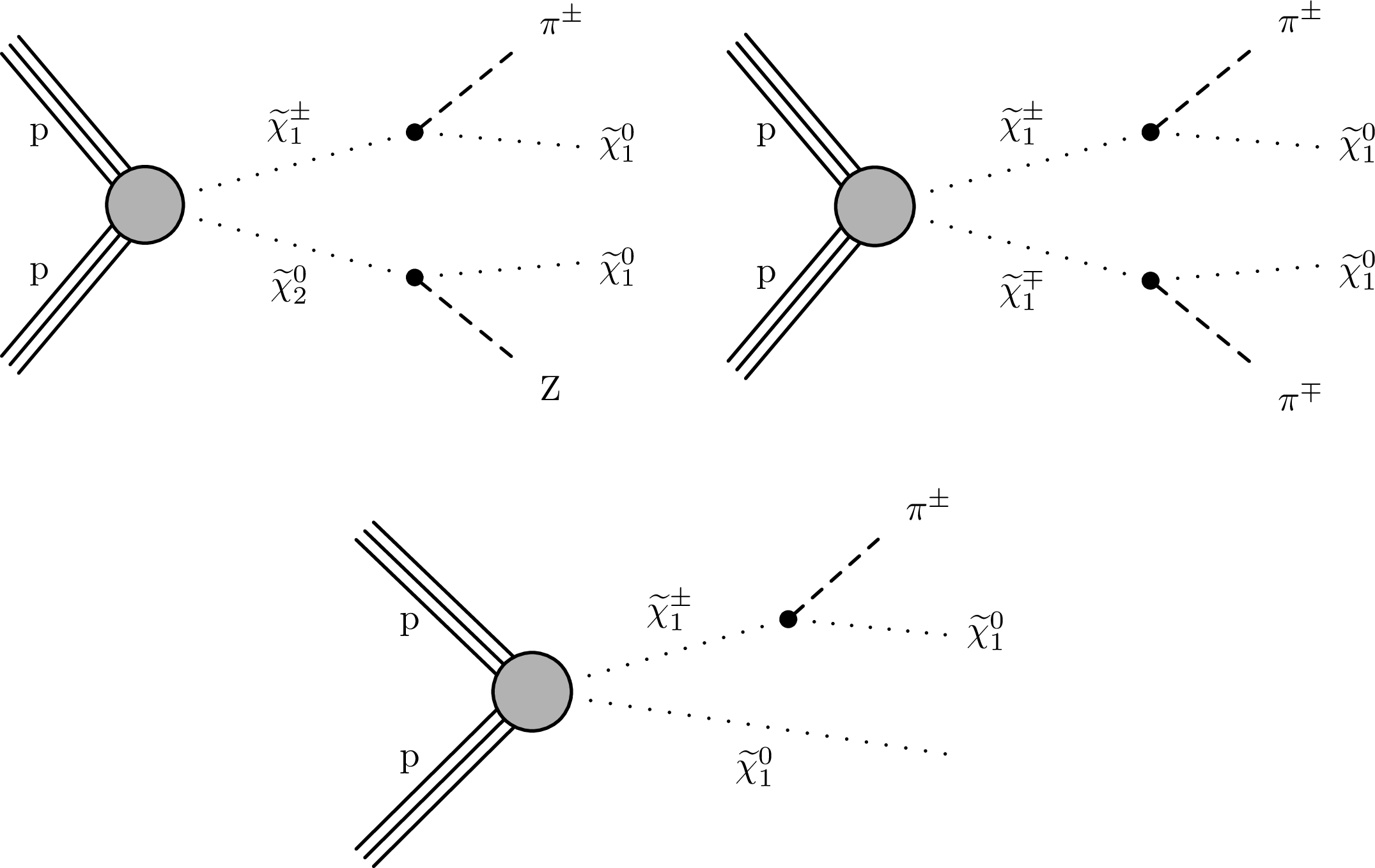

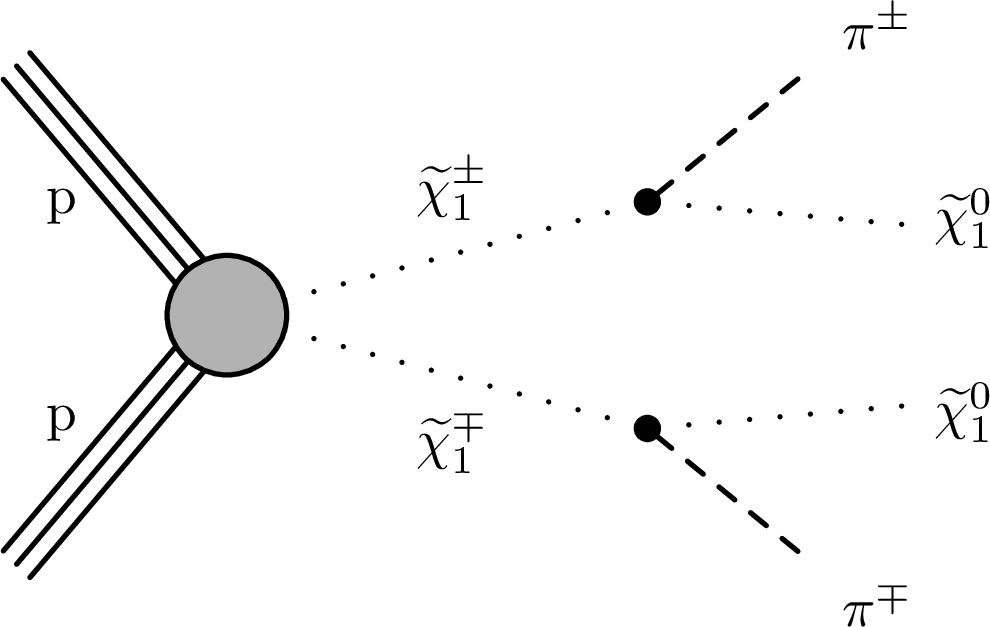

Figure 3:

Diagrams for the AMSB $ \tilde{\chi}_{1}^{\pm} \to \tilde{\chi}_{1}^{0}+\mathrm{X} $ process. The $ \mathrm{X} $ particle is shown here as a charged pion $ \pi^{\pm} $, but $ \mathrm{X} $ can also be an electron or a muon, depending on the type of neutralino $ \tilde{\chi}_{1}^{0} $. |

png pdf |

Figure 3-a:

Diagrams for the AMSB $ \tilde{\chi}_{1}^{\pm} \to \tilde{\chi}_{1}^{0}+\mathrm{X} $ process. The $ \mathrm{X} $ particle is shown here as a charged pion $ \pi^{\pm} $, but $ \mathrm{X} $ can also be an electron or a muon, depending on the type of neutralino $ \tilde{\chi}_{1}^{0} $. |

png pdf |

Figure 3-b:

Diagrams for the AMSB $ \tilde{\chi}_{1}^{\pm} \to \tilde{\chi}_{1}^{0}+\mathrm{X} $ process. The $ \mathrm{X} $ particle is shown here as a charged pion $ \pi^{\pm} $, but $ \mathrm{X} $ can also be an electron or a muon, depending on the type of neutralino $ \tilde{\chi}_{1}^{0} $. |

png pdf |

Figure 3-c:

Diagrams for the AMSB $ \tilde{\chi}_{1}^{\pm} \to \tilde{\chi}_{1}^{0}+\mathrm{X} $ process. The $ \mathrm{X} $ particle is shown here as a charged pion $ \pi^{\pm} $, but $ \mathrm{X} $ can also be an electron or a muon, depending on the type of neutralino $ \tilde{\chi}_{1}^{0} $. |

png pdf |

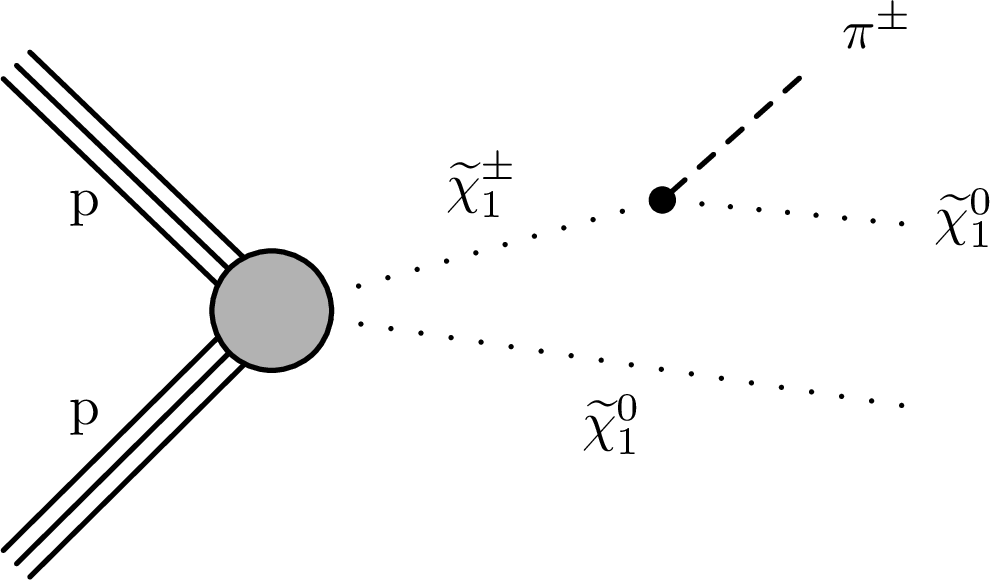

Figure 4:

Diagram for the $ \mathrm{H} \to \mathrm{X}\mathrm{X} $ or $ \mathrm{H} \to \text{S}\text{S} $ process. |

png pdf |

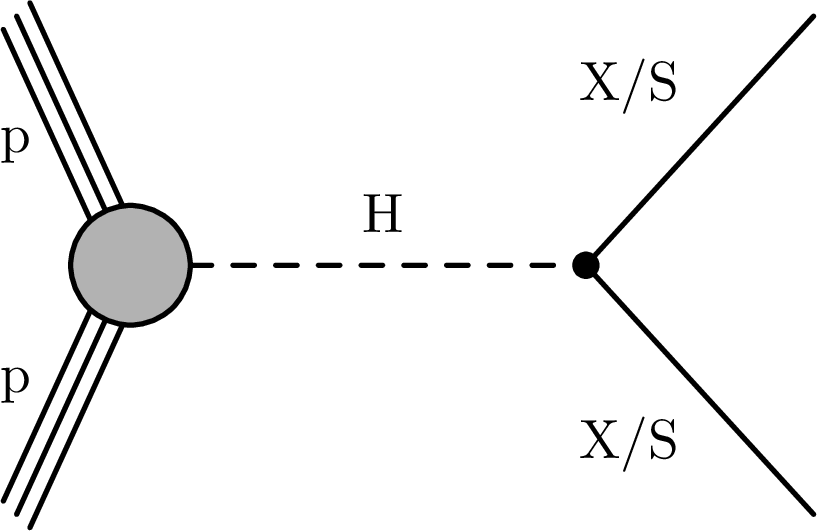

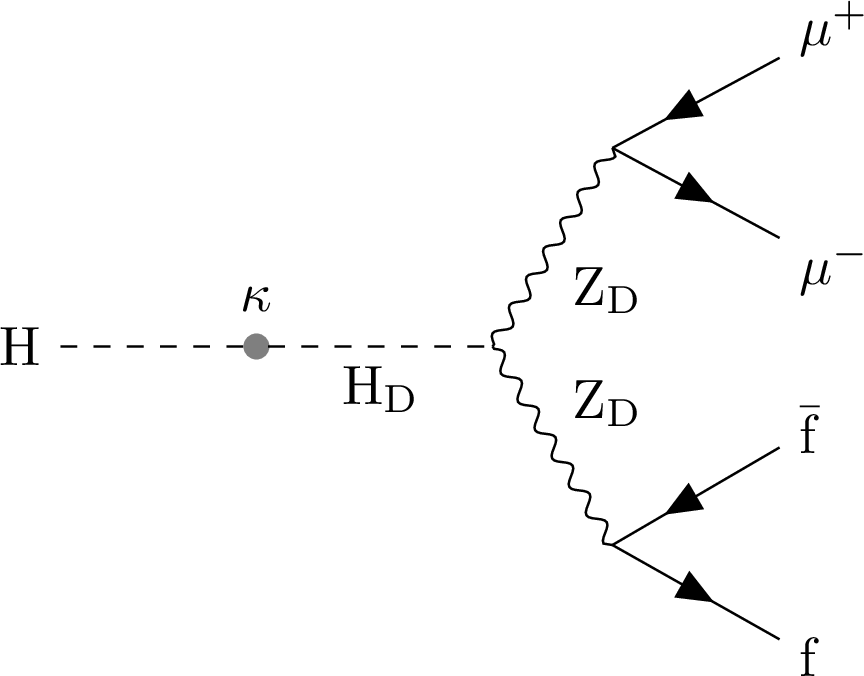

Figure 5:

Diagram for the $ \mathrm{H} \to \mathrm{Z}_\text{D}\mathrm{Z}_\text{D} $ process. |

png pdf |

Figure 6:

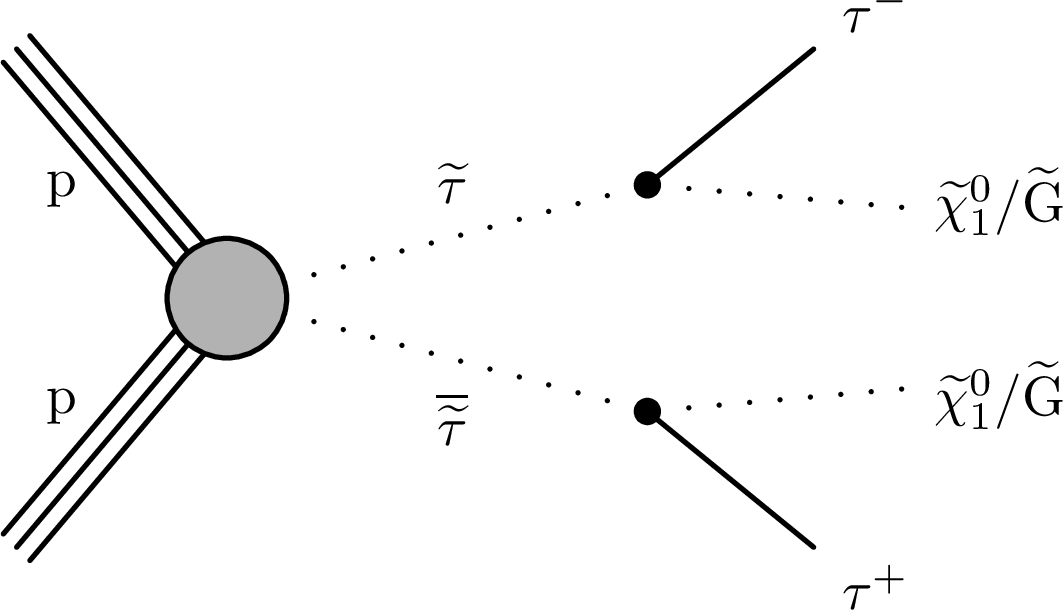

Diagram for the direct $ \tilde{\tau} $ pair production process, with each $ \tilde{\tau} $ decaying to a $ \tau $ lepton and a neutralino $ \tilde{\chi}_{1}^{0} $ (or a gravitino $ \tilde{\mathrm{G}} $). |

png pdf |

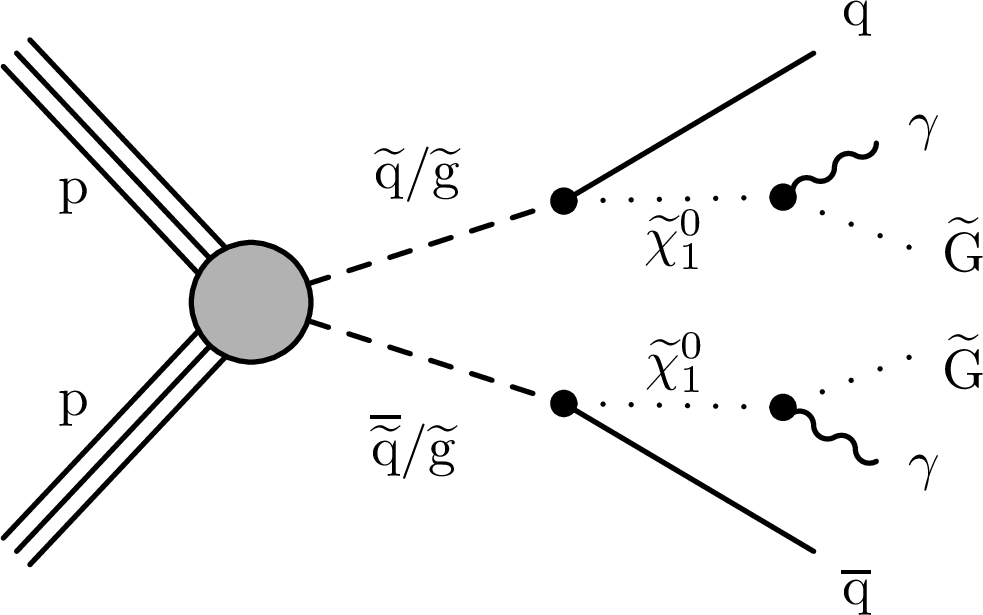

Figure 7:

Diagram for the GMSB SPS8 benchmark model, where pair-produced squarks $ \tilde{\mathrm{q}} $ and gluinos $ \mathrm{\widetilde{g}} $ undergo cascade decays and eventually produce a gravitino $ \tilde{\mathrm{G}} $. |

png pdf |

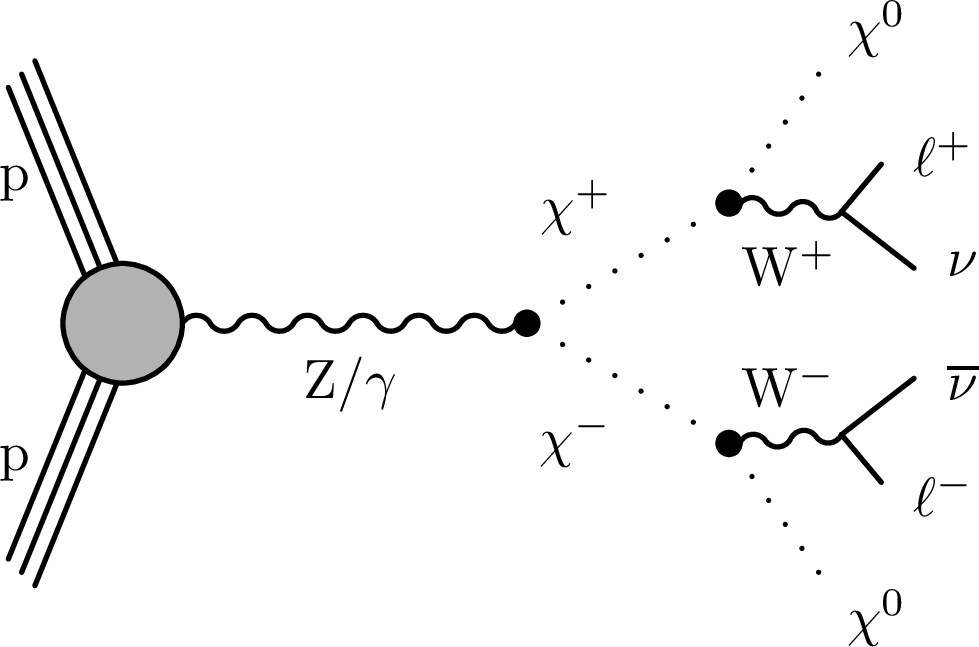

Figure 8:

Diagram for the singlet-triplet Higgs portal dark matter benchmark model, where a charged dark partner particle $ \chi^{\pm} $ in a compressed dark sector decays via an off-shell W boson and produces a stable neutral dark matter candidate $ \chi^{0} $. |

png pdf |

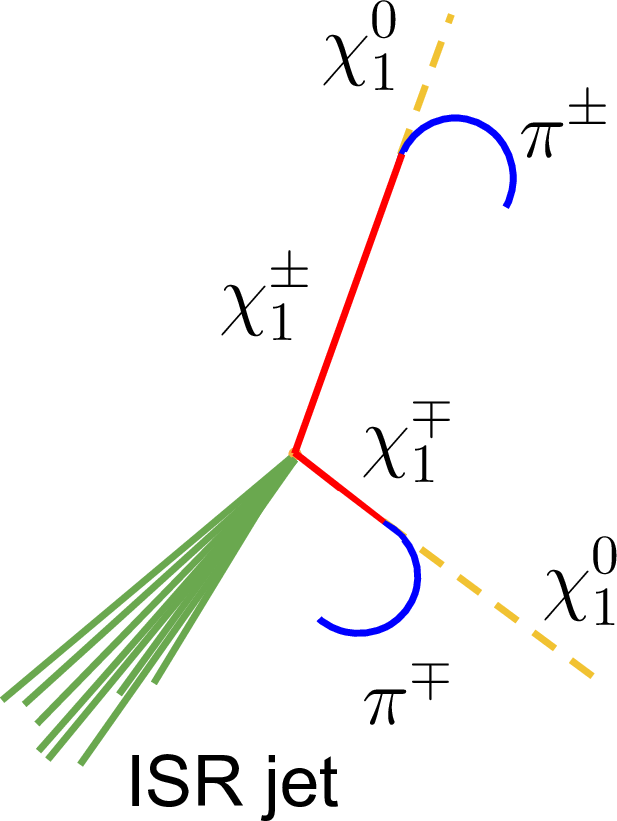

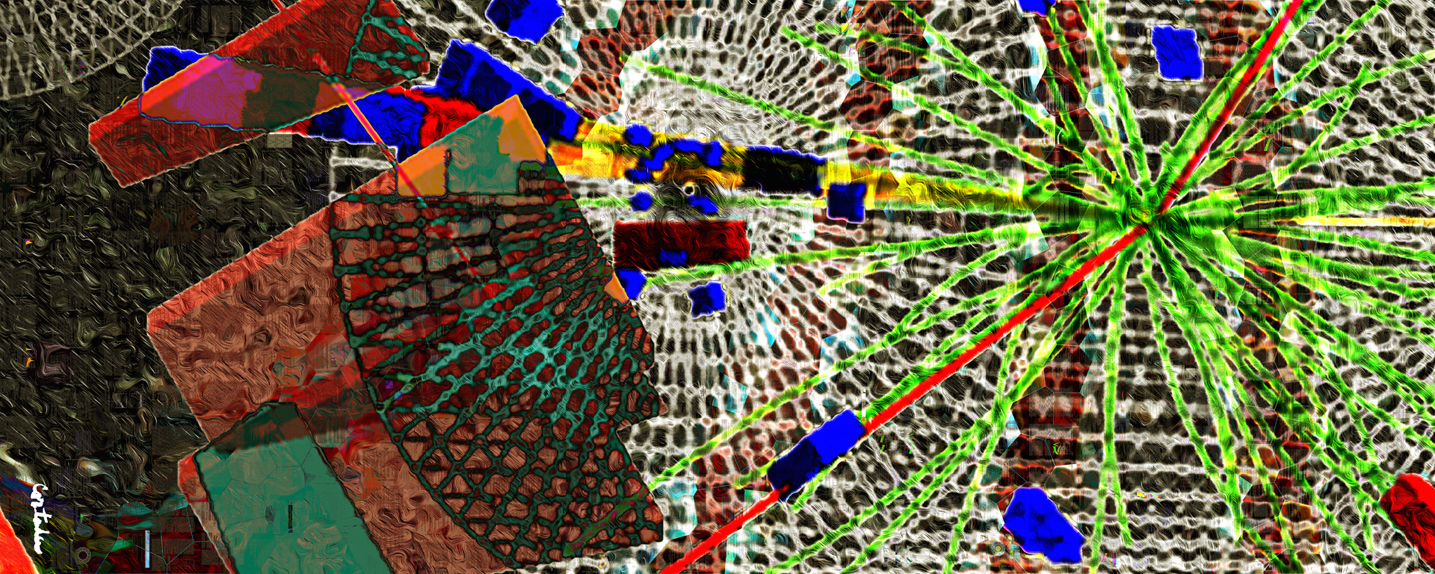

Figure 9:

Diagram of a disappearing-track event. Each $ \tilde{\chi}_{1}^{\pm} $ (solid red lines) is an LLP that decays in the tracker and recoils off an ISR jet (multiple solid green lines), while the $ \tilde{\chi}_{1}^{0} $ (dashed yellow line) is undetected, and the $ \pi^{\pm} $ (blue curve) is not reconstructed because of its low $ p_{\mathrm{T}} $. The recoil of the disappearing track against the ISR jet produces measurable calorimeter and PF $ p_{\mathrm{T}}^\text{miss} $. |

png pdf |

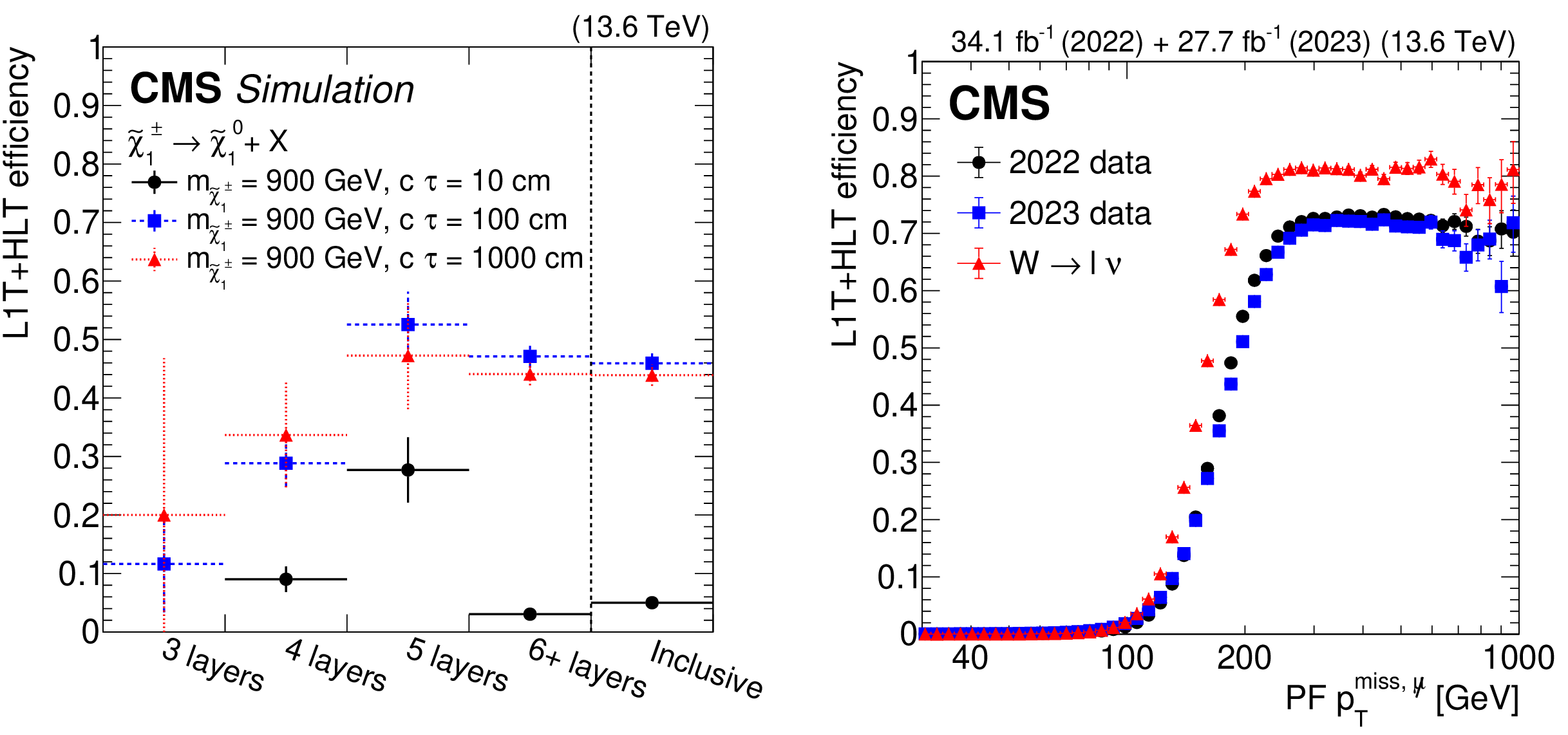

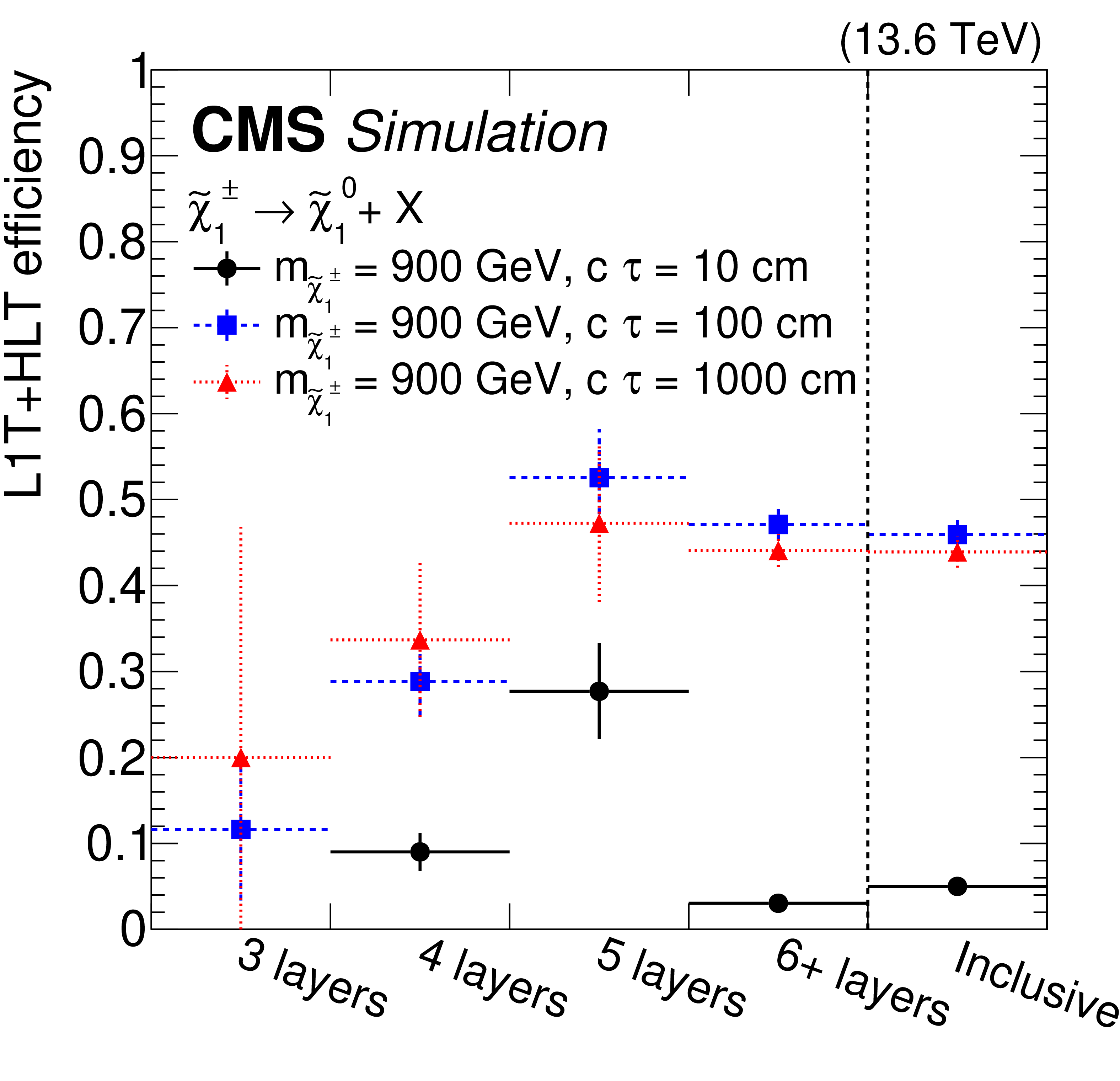

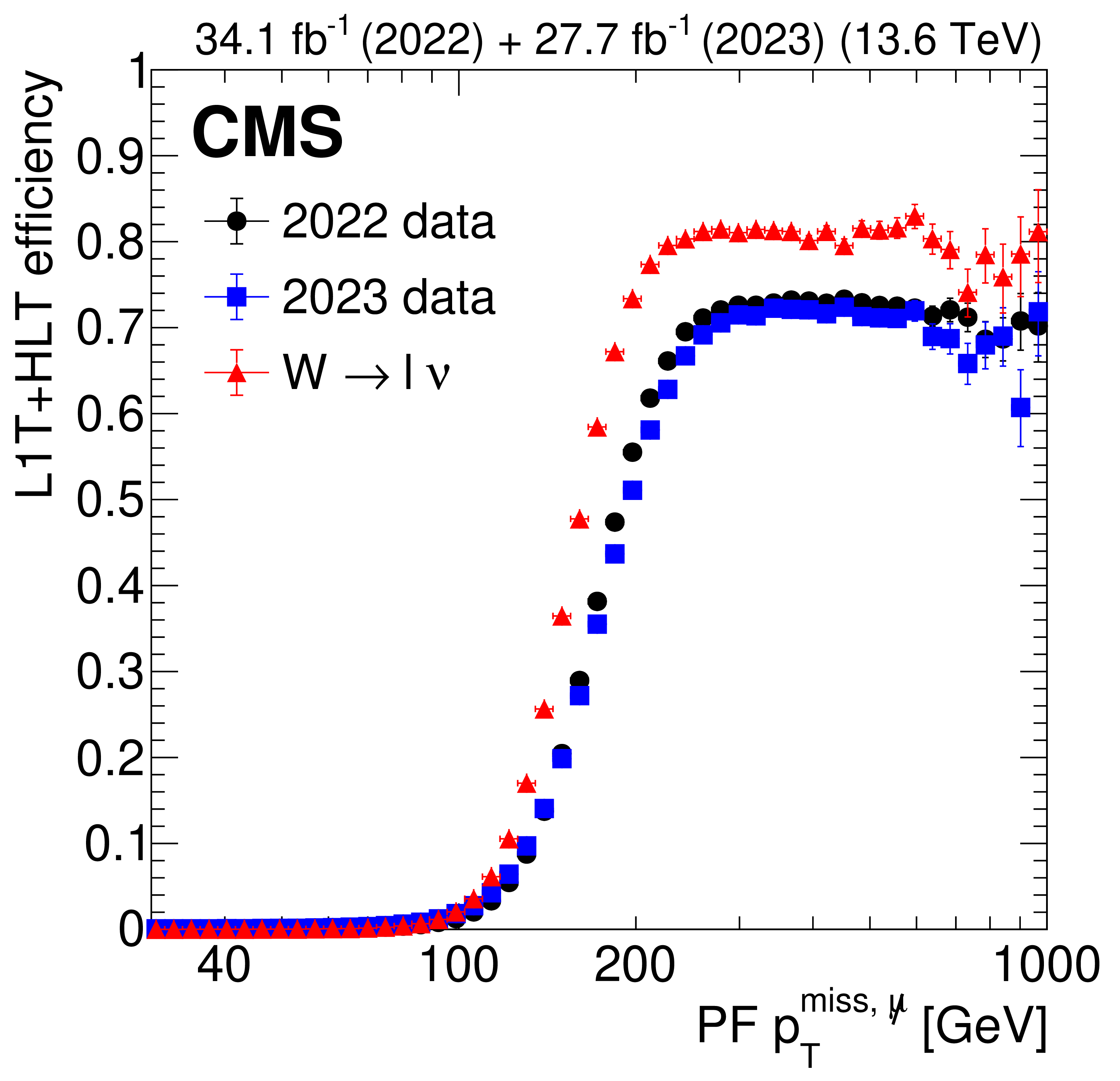

Figure 10:

The L1T+HLT efficiency of the disappearing-track trigger: Efficiency as a function of the number of tracker layers with valid measurements for tracks that pass the offline requirements described in Table 3, in $ \tilde{\chi}_{1}^{\pm} \to \tilde{\chi}_{1}^{0}+\mathrm{X} $ simulated events for 2022 conditions, where $ m_{\tilde{\chi}_{1}^{\pm}}= $ 900 GeV and $ \tilde{\chi}_{1}^{0} $ is nearly mass-degenerate with $ \tilde{\chi}_{1}^{\pm} $ (left). The efficiency is shown for LLPs with $ c\tau= $ 10, 100, and 1000$ \text{cm} $ in black circles, blue squares, and red triangles, respectively. Comparison of efficiencies calculated with 2022 data (black circles), 2023 data (blue squares), and $ \mathrm{W} \to \ell\nu $ simulation (red triangles), as a function of offline reconstructed PF $ p_{\mathrm{T}}^{\text{miss}, \not{\mu}} $ (right). The efficiency rises to a plateau of less than 100% because of the isolated track leg of the algorithm. |

png pdf |

Figure 10-a:

The L1T+HLT efficiency of the disappearing-track trigger: Efficiency as a function of the number of tracker layers with valid measurements for tracks that pass the offline requirements described in Table 3, in $ \tilde{\chi}_{1}^{\pm} \to \tilde{\chi}_{1}^{0}+\mathrm{X} $ simulated events for 2022 conditions, where $ m_{\tilde{\chi}_{1}^{\pm}}= $ 900 GeV and $ \tilde{\chi}_{1}^{0} $ is nearly mass-degenerate with $ \tilde{\chi}_{1}^{\pm} $ (left). The efficiency is shown for LLPs with $ c\tau= $ 10, 100, and 1000$ \text{cm} $ in black circles, blue squares, and red triangles, respectively. Comparison of efficiencies calculated with 2022 data (black circles), 2023 data (blue squares), and $ \mathrm{W} \to \ell\nu $ simulation (red triangles), as a function of offline reconstructed PF $ p_{\mathrm{T}}^{\text{miss}, \not{\mu}} $ (right). The efficiency rises to a plateau of less than 100% because of the isolated track leg of the algorithm. |

png pdf |

Figure 10-b:

The L1T+HLT efficiency of the disappearing-track trigger: Efficiency as a function of the number of tracker layers with valid measurements for tracks that pass the offline requirements described in Table 3, in $ \tilde{\chi}_{1}^{\pm} \to \tilde{\chi}_{1}^{0}+\mathrm{X} $ simulated events for 2022 conditions, where $ m_{\tilde{\chi}_{1}^{\pm}}= $ 900 GeV and $ \tilde{\chi}_{1}^{0} $ is nearly mass-degenerate with $ \tilde{\chi}_{1}^{\pm} $ (left). The efficiency is shown for LLPs with $ c\tau= $ 10, 100, and 1000$ \text{cm} $ in black circles, blue squares, and red triangles, respectively. Comparison of efficiencies calculated with 2022 data (black circles), 2023 data (blue squares), and $ \mathrm{W} \to \ell\nu $ simulation (red triangles), as a function of offline reconstructed PF $ p_{\mathrm{T}}^{\text{miss}, \not{\mu}} $ (right). The efficiency rises to a plateau of less than 100% because of the isolated track leg of the algorithm. |

png pdf |

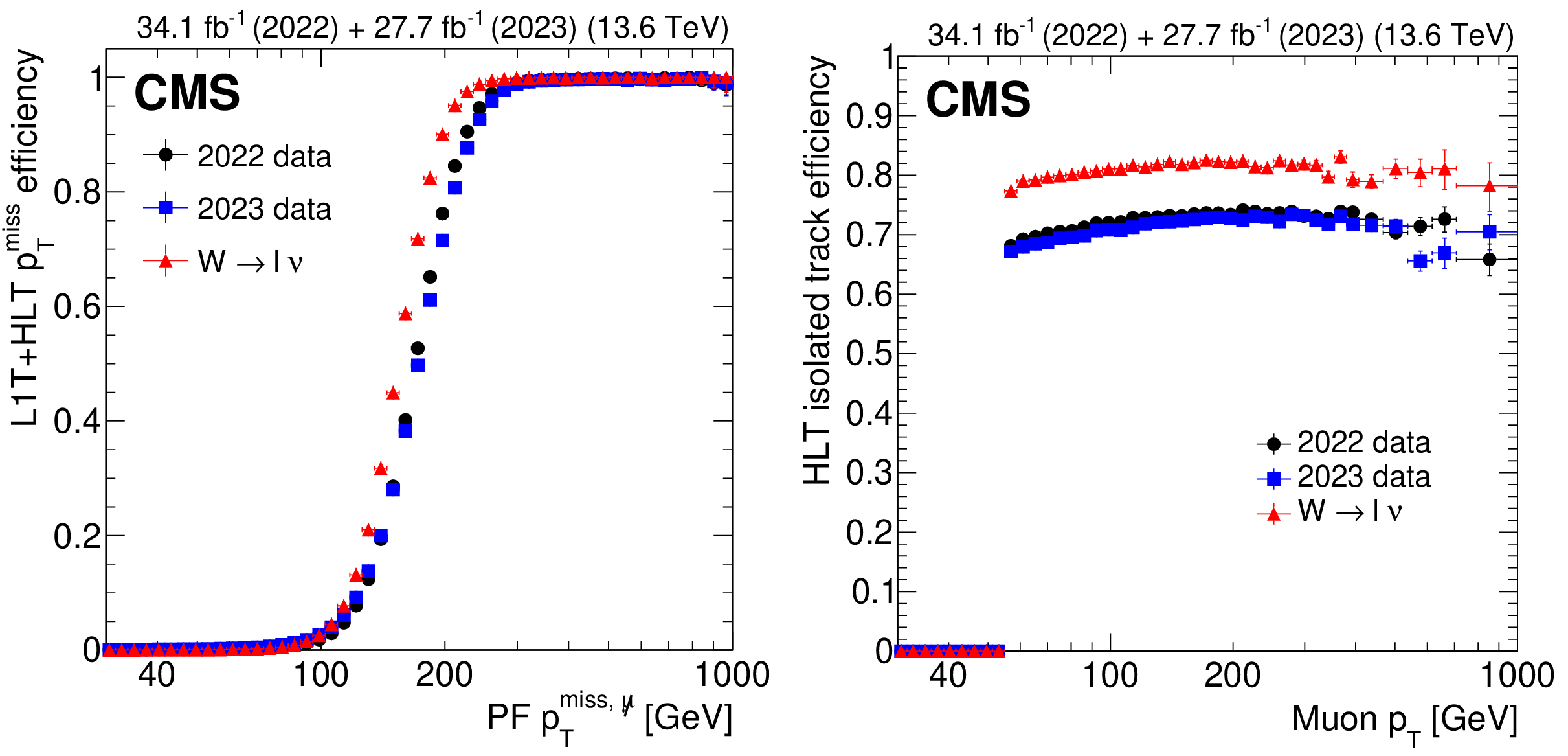

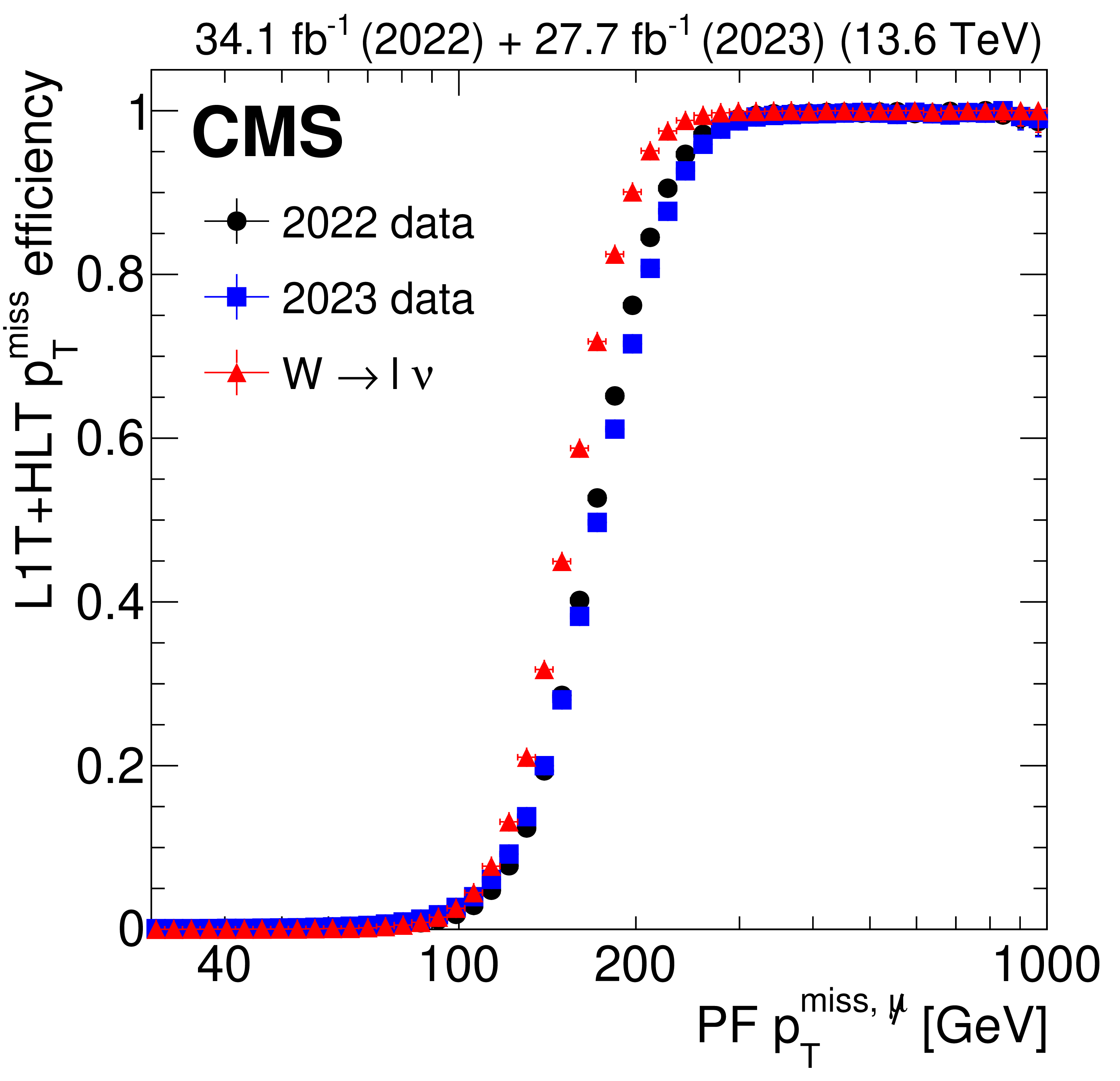

Figure 11:

The L1T+HLT efficiency of each leg of the disappearing-track trigger in 2022 data (black circles), 2023 data (blue squares), and $ \mathrm{W} \to \ell\nu $ simulation (red triangles). Efficiency of the L1T+HLT $ p_{\mathrm{T}}^\text{miss} $ leg as a function of offline reconstructed PF $ p_{\mathrm{T}}^{\text{miss}, \not{\mu}} $ (left). Efficiency of the full HLT path, taking into account only events that already passed through the $ p_{\mathrm{T}}^\text{miss} $ leg, as a function of the selected muon $ p_{\mathrm{T}} $ (right). |

png pdf |

Figure 11-a:

The L1T+HLT efficiency of each leg of the disappearing-track trigger in 2022 data (black circles), 2023 data (blue squares), and $ \mathrm{W} \to \ell\nu $ simulation (red triangles). Efficiency of the L1T+HLT $ p_{\mathrm{T}}^\text{miss} $ leg as a function of offline reconstructed PF $ p_{\mathrm{T}}^{\text{miss}, \not{\mu}} $ (left). Efficiency of the full HLT path, taking into account only events that already passed through the $ p_{\mathrm{T}}^\text{miss} $ leg, as a function of the selected muon $ p_{\mathrm{T}} $ (right). |

png pdf |

Figure 11-b:

The L1T+HLT efficiency of each leg of the disappearing-track trigger in 2022 data (black circles), 2023 data (blue squares), and $ \mathrm{W} \to \ell\nu $ simulation (red triangles). Efficiency of the L1T+HLT $ p_{\mathrm{T}}^\text{miss} $ leg as a function of offline reconstructed PF $ p_{\mathrm{T}}^{\text{miss}, \not{\mu}} $ (left). Efficiency of the full HLT path, taking into account only events that already passed through the $ p_{\mathrm{T}}^\text{miss} $ leg, as a function of the selected muon $ p_{\mathrm{T}} $ (right). |

png pdf |

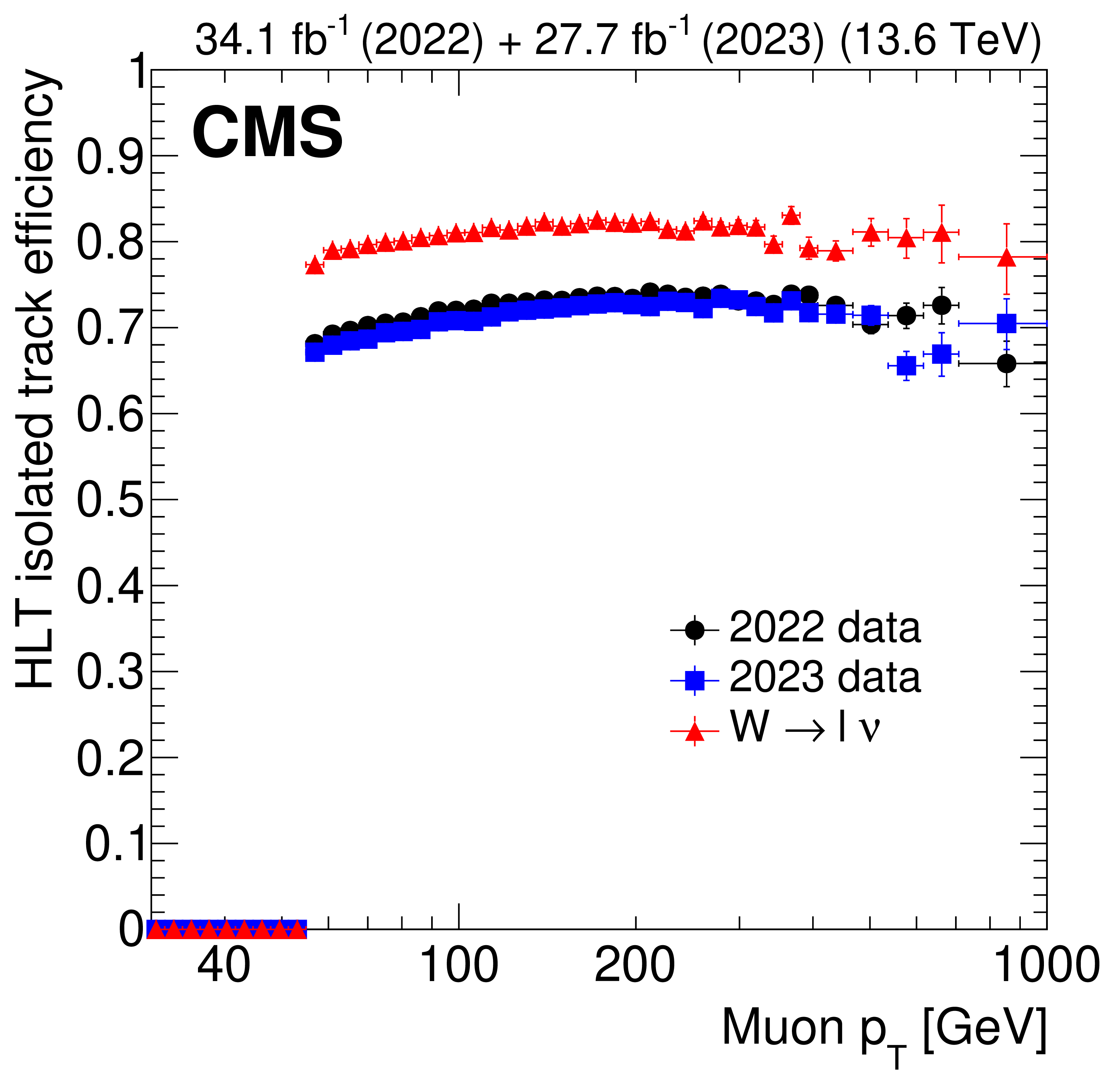

Figure 12:

Event display of simulated $ \tilde{\tau} $ pair production in a GMSB benchmark model, followed by the decay of each $ \tilde{\tau} $ to a $ \tau $ lepton and a neutralino $ \tilde{\chi}_{1}^{0} $, with the $ \tau $ leptons decaying hadronically. The magenta lines indicate the $ \tilde{\tau} $ particles, the light blue lines indicate the neutralinos, and the red lines indicate the $ \tau $ leptons decaying hadronically. The shaded dark yellow cones show the two reconstructed jets, and the orange lines inside the jets are the hadrons from the $ \tau $ decay. |

png pdf |

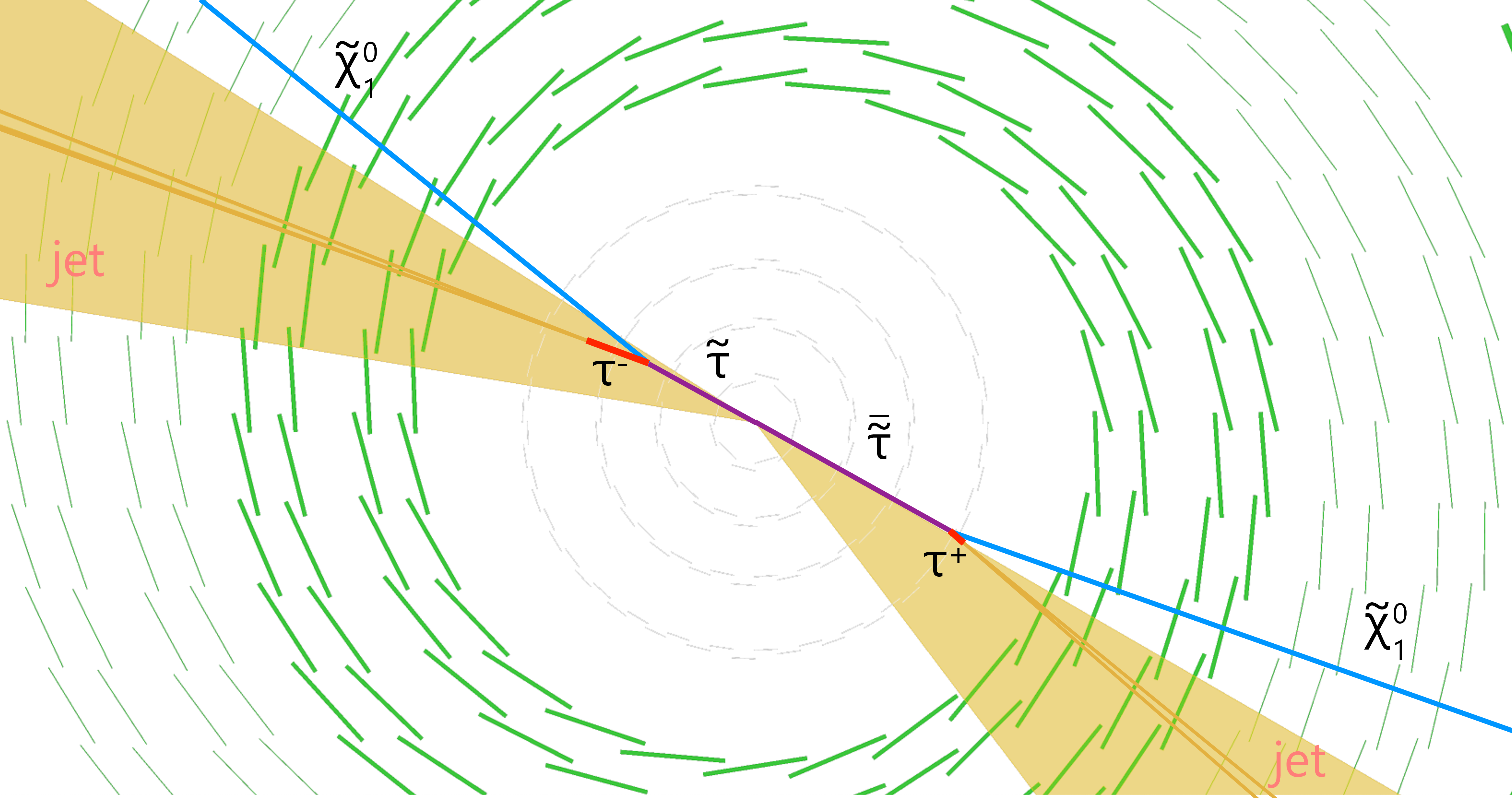

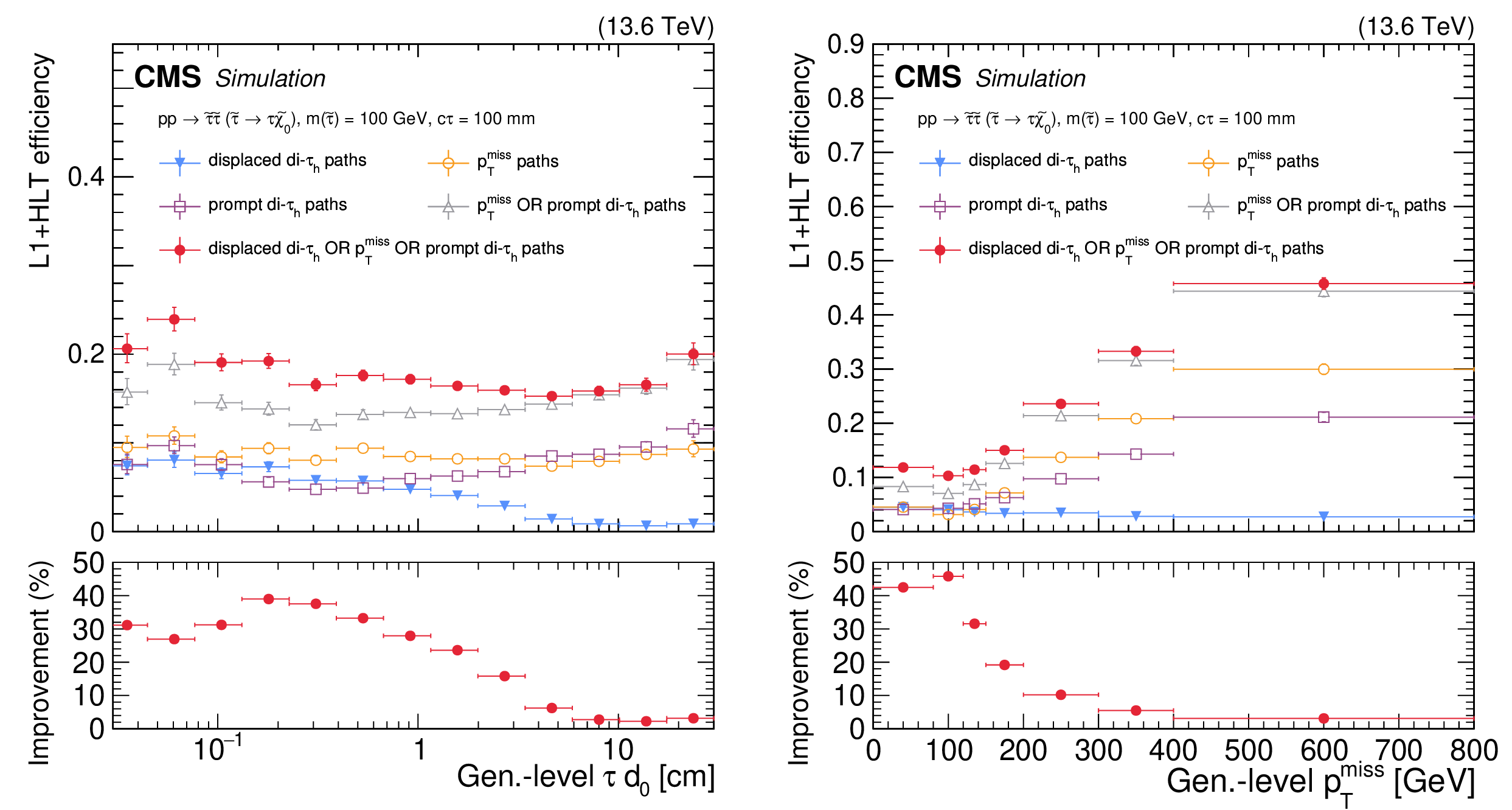

Figure 13:

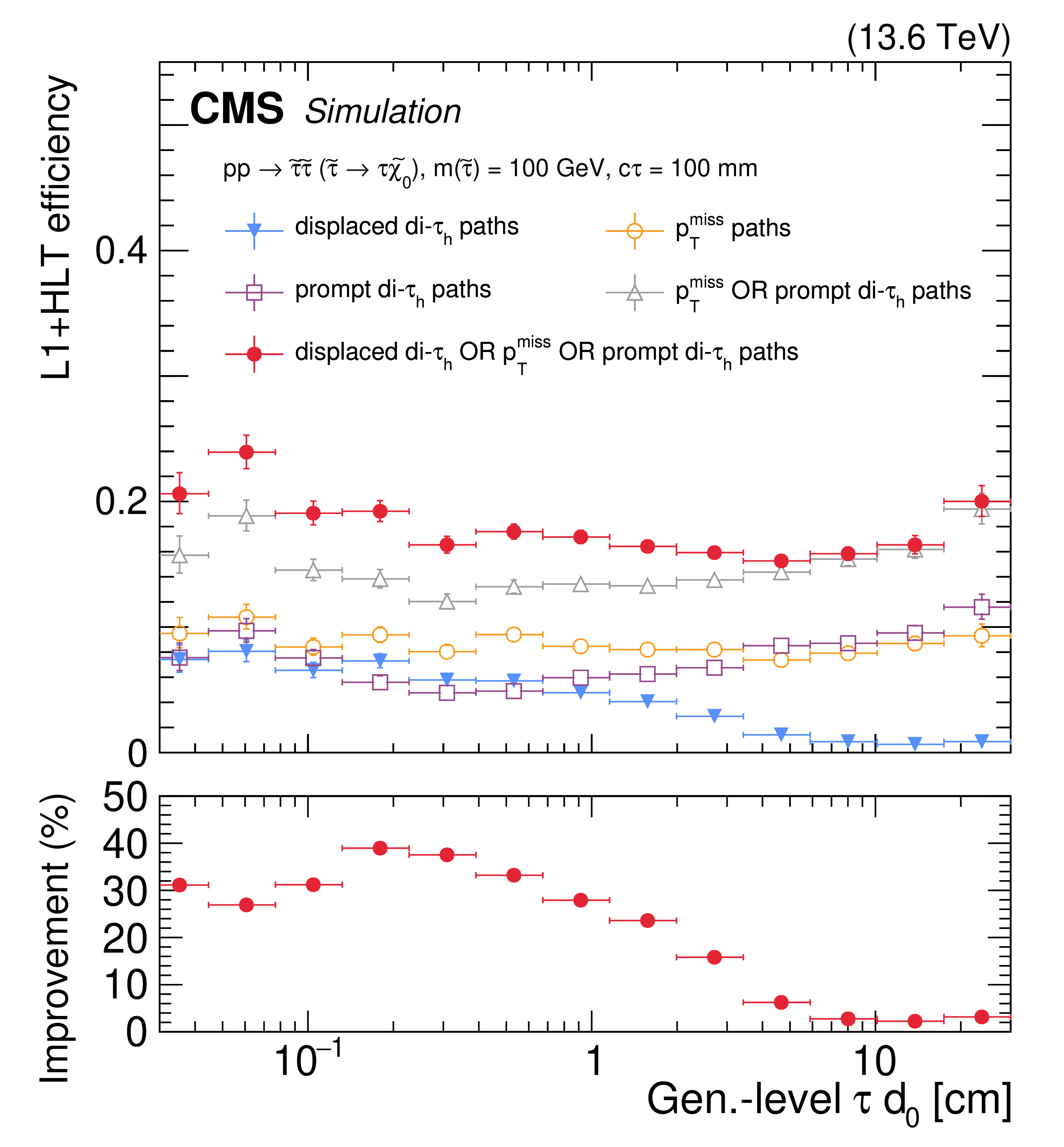

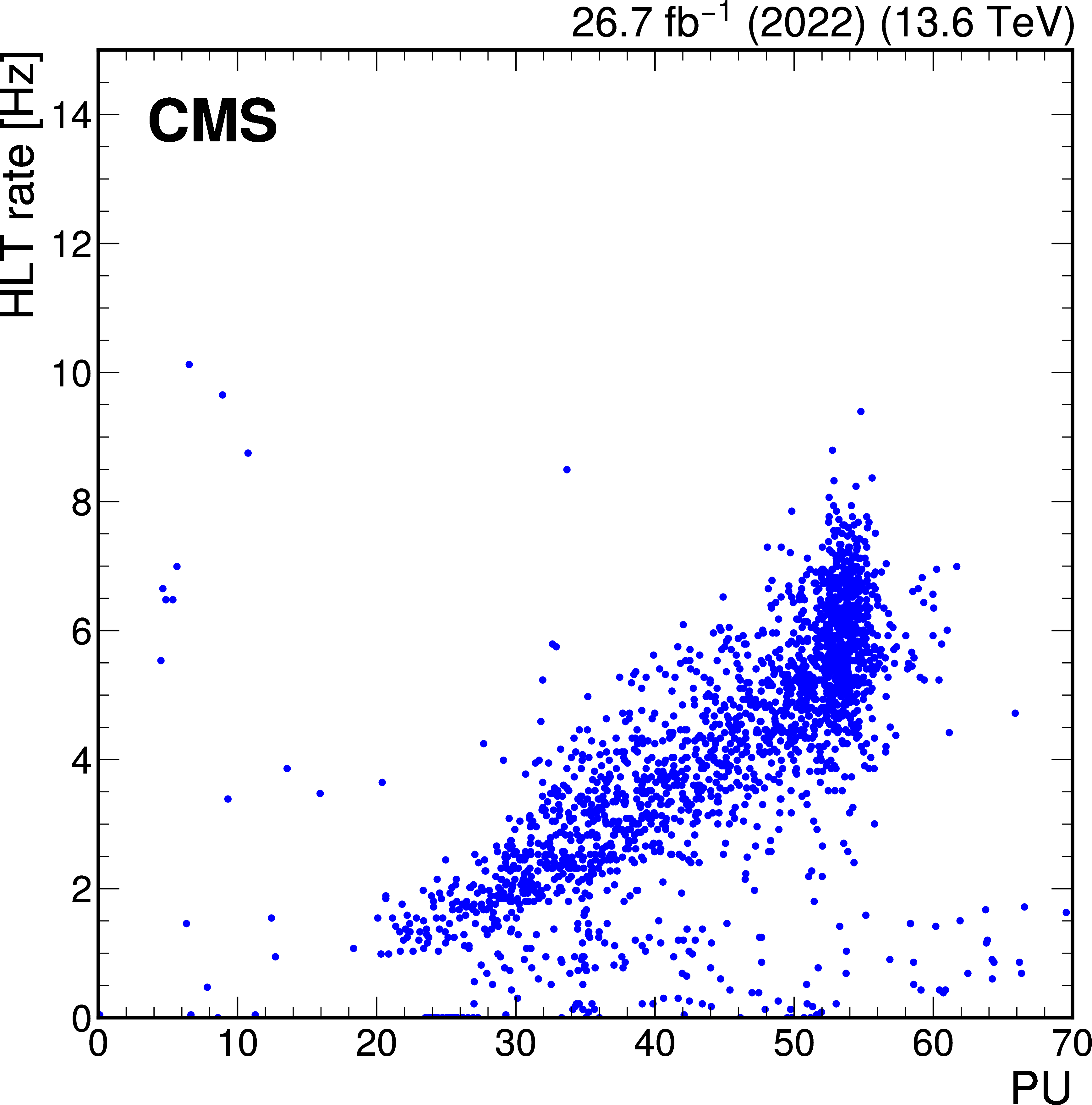

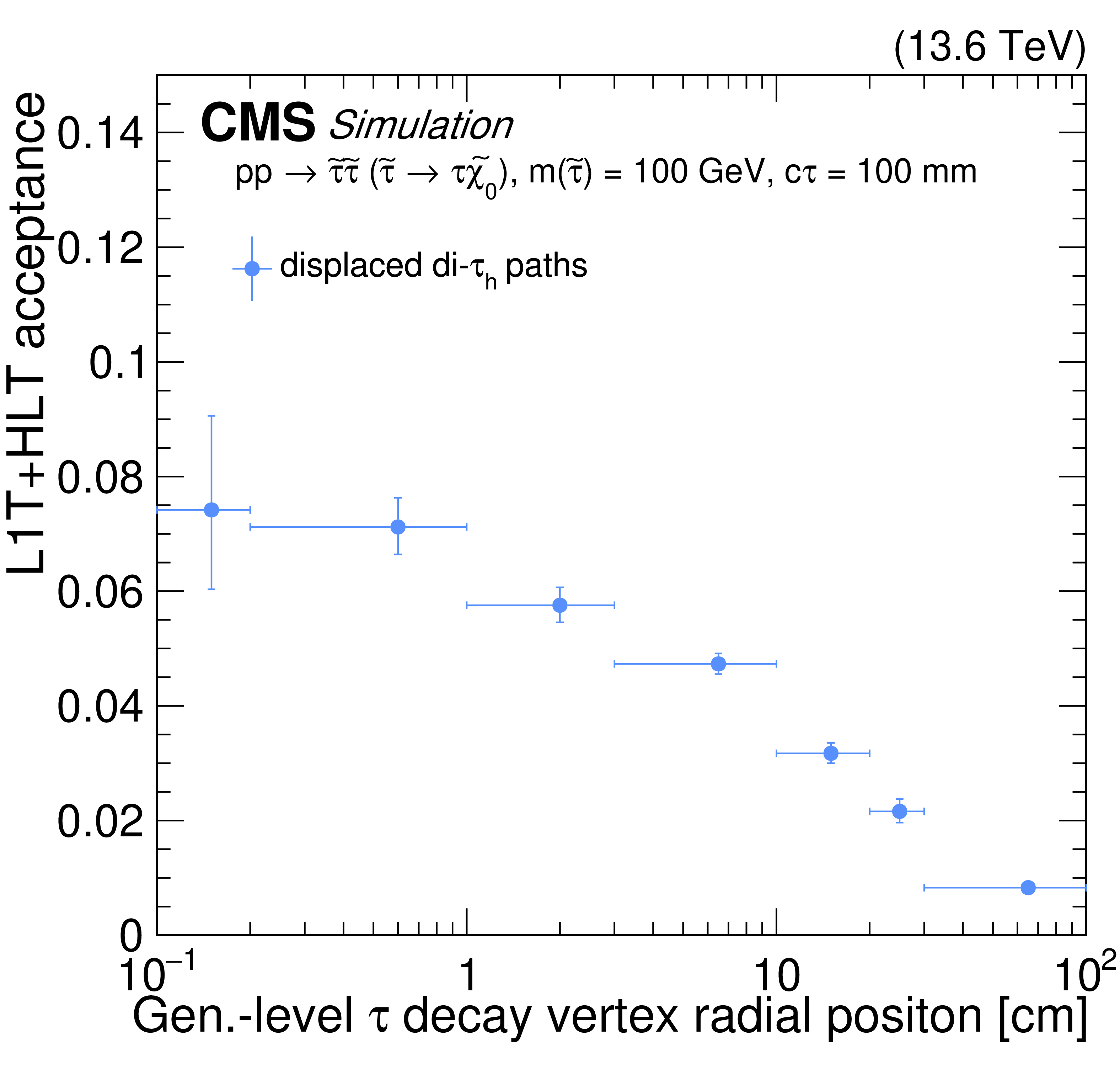

The L1T+HLT efficiency of the displaced $ \tau_\mathrm{h} $ trigger, for simulated $ \mathrm{p}\mathrm{p} \to \tilde{\tau}\tilde{\tau} (\tilde{\tau} \to \tau\tilde{\chi}_{1}^{0}) $ events, where the $ \tilde{\tau} $ has $ c\tau = 10 \text{cm} $ and each $ \tau $ decays hadronically. The efficiency is shown as a function of the $ d_{\text{0}} $ of the highest $ p_{\mathrm{T}} \tau $ lepton in the event (left) and as a function of $ p_{\mathrm{T}}^\text{miss} $ (right). The efficiency is shown for the displaced di-$ \tau_\mathrm{h} $ trigger path (blue filled triangles), the previously available $ p_{\mathrm{T}}^\text{miss} $-based paths (orange open circles), the previously available prompt di-$ \tau_\mathrm{h} $ paths (purple open squares), the combination of the $ p_{\mathrm{T}}^\text{miss} $-based and prompt di-$ \tau_\mathrm{h} $ paths (gray open triangles), and the combination of the $ p_{\mathrm{T}}^\text{miss} $-based, prompt di-$ \tau_\mathrm{h} $, and displaced di-$ \tau_\mathrm{h} $ paths (red filled circles), using 2022 data-taking conditions. The efficiency is evaluated with respect to events that contain at least two generator-level $ \tau $ leptons, where the visible component of the $ \tau $ lepton $ p_{\mathrm{T}} $ is greater than 30 GeV and $ |\eta| < $ 2.1. The lower panels show the ratio (improvement in %) of the trigger efficiency given by the combination of the displaced di-$ \tau_\mathrm{h} $ trigger path with the $ p_{\mathrm{T}}^\text{miss} $-based and prompt di-$ \tau_\mathrm{h} $ paths to that of the combination of the previously available $ p_{\mathrm{T}}^\text{miss} $-based and prompt di-$ \tau_\mathrm{h} $ paths. |

png pdf |

Figure 13-a:

The L1T+HLT efficiency of the displaced $ \tau_\mathrm{h} $ trigger, for simulated $ \mathrm{p}\mathrm{p} \to \tilde{\tau}\tilde{\tau} (\tilde{\tau} \to \tau\tilde{\chi}_{1}^{0}) $ events, where the $ \tilde{\tau} $ has $ c\tau = 10 \text{cm} $ and each $ \tau $ decays hadronically. The efficiency is shown as a function of the $ d_{\text{0}} $ of the highest $ p_{\mathrm{T}} \tau $ lepton in the event (left) and as a function of $ p_{\mathrm{T}}^\text{miss} $ (right). The efficiency is shown for the displaced di-$ \tau_\mathrm{h} $ trigger path (blue filled triangles), the previously available $ p_{\mathrm{T}}^\text{miss} $-based paths (orange open circles), the previously available prompt di-$ \tau_\mathrm{h} $ paths (purple open squares), the combination of the $ p_{\mathrm{T}}^\text{miss} $-based and prompt di-$ \tau_\mathrm{h} $ paths (gray open triangles), and the combination of the $ p_{\mathrm{T}}^\text{miss} $-based, prompt di-$ \tau_\mathrm{h} $, and displaced di-$ \tau_\mathrm{h} $ paths (red filled circles), using 2022 data-taking conditions. The efficiency is evaluated with respect to events that contain at least two generator-level $ \tau $ leptons, where the visible component of the $ \tau $ lepton $ p_{\mathrm{T}} $ is greater than 30 GeV and $ |\eta| < $ 2.1. The lower panels show the ratio (improvement in %) of the trigger efficiency given by the combination of the displaced di-$ \tau_\mathrm{h} $ trigger path with the $ p_{\mathrm{T}}^\text{miss} $-based and prompt di-$ \tau_\mathrm{h} $ paths to that of the combination of the previously available $ p_{\mathrm{T}}^\text{miss} $-based and prompt di-$ \tau_\mathrm{h} $ paths. |

png pdf |

Figure 13-b:

The L1T+HLT efficiency of the displaced $ \tau_\mathrm{h} $ trigger, for simulated $ \mathrm{p}\mathrm{p} \to \tilde{\tau}\tilde{\tau} (\tilde{\tau} \to \tau\tilde{\chi}_{1}^{0}) $ events, where the $ \tilde{\tau} $ has $ c\tau = 10 \text{cm} $ and each $ \tau $ decays hadronically. The efficiency is shown as a function of the $ d_{\text{0}} $ of the highest $ p_{\mathrm{T}} \tau $ lepton in the event (left) and as a function of $ p_{\mathrm{T}}^\text{miss} $ (right). The efficiency is shown for the displaced di-$ \tau_\mathrm{h} $ trigger path (blue filled triangles), the previously available $ p_{\mathrm{T}}^\text{miss} $-based paths (orange open circles), the previously available prompt di-$ \tau_\mathrm{h} $ paths (purple open squares), the combination of the $ p_{\mathrm{T}}^\text{miss} $-based and prompt di-$ \tau_\mathrm{h} $ paths (gray open triangles), and the combination of the $ p_{\mathrm{T}}^\text{miss} $-based, prompt di-$ \tau_\mathrm{h} $, and displaced di-$ \tau_\mathrm{h} $ paths (red filled circles), using 2022 data-taking conditions. The efficiency is evaluated with respect to events that contain at least two generator-level $ \tau $ leptons, where the visible component of the $ \tau $ lepton $ p_{\mathrm{T}} $ is greater than 30 GeV and $ |\eta| < $ 2.1. The lower panels show the ratio (improvement in %) of the trigger efficiency given by the combination of the displaced di-$ \tau_\mathrm{h} $ trigger path with the $ p_{\mathrm{T}}^\text{miss} $-based and prompt di-$ \tau_\mathrm{h} $ paths to that of the combination of the previously available $ p_{\mathrm{T}}^\text{miss} $-based and prompt di-$ \tau_\mathrm{h} $ paths. |

png pdf |

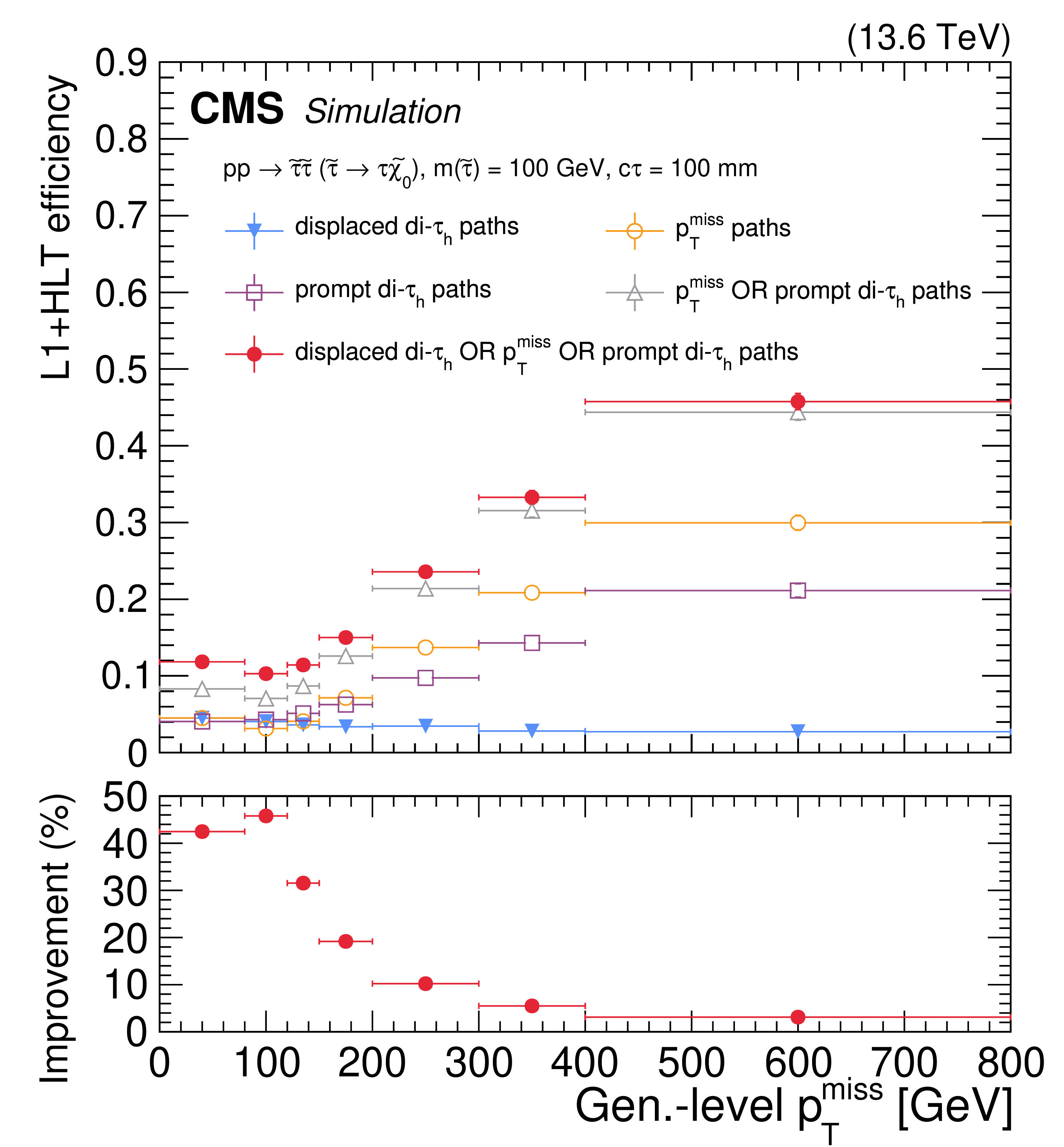

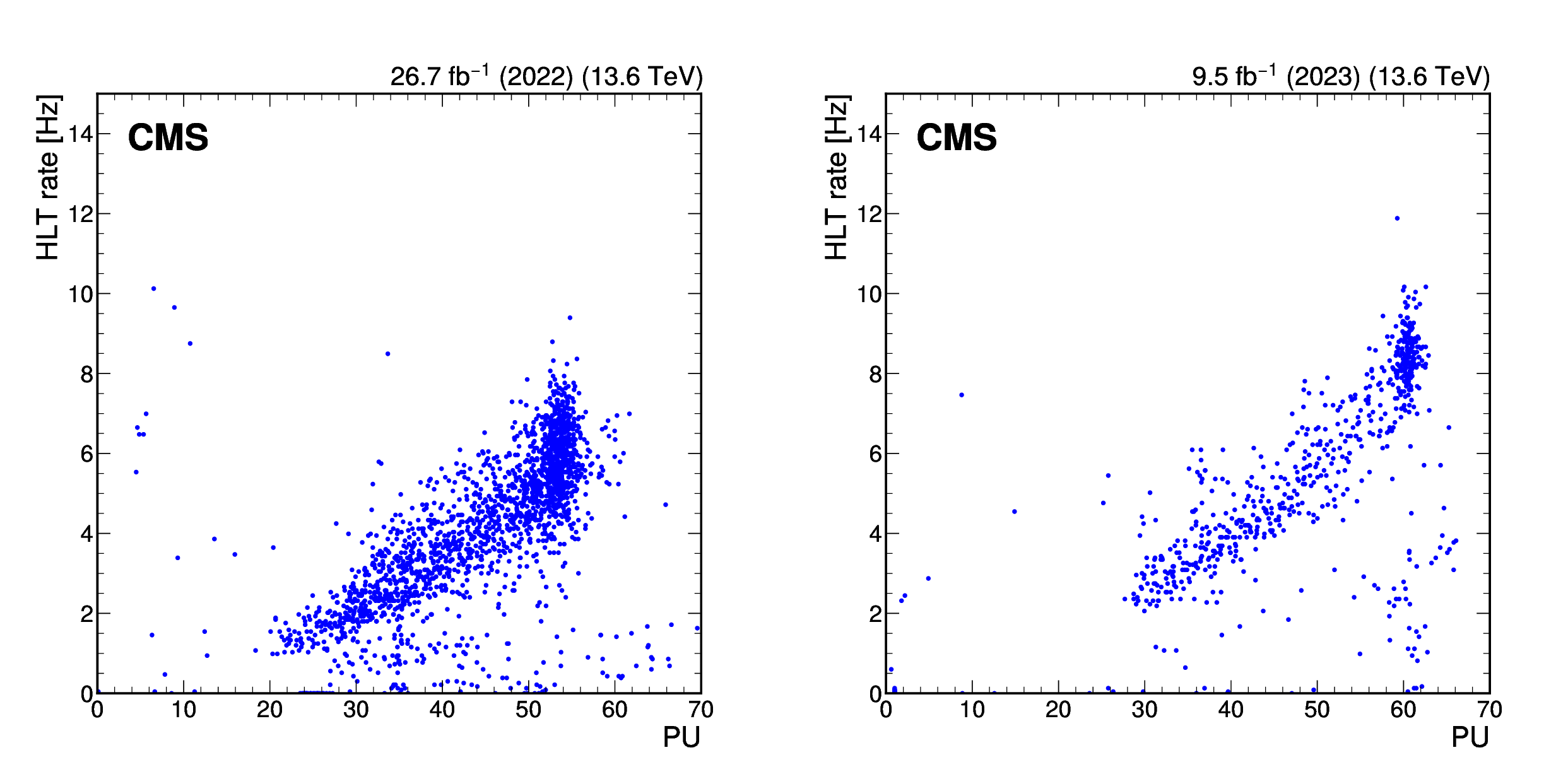

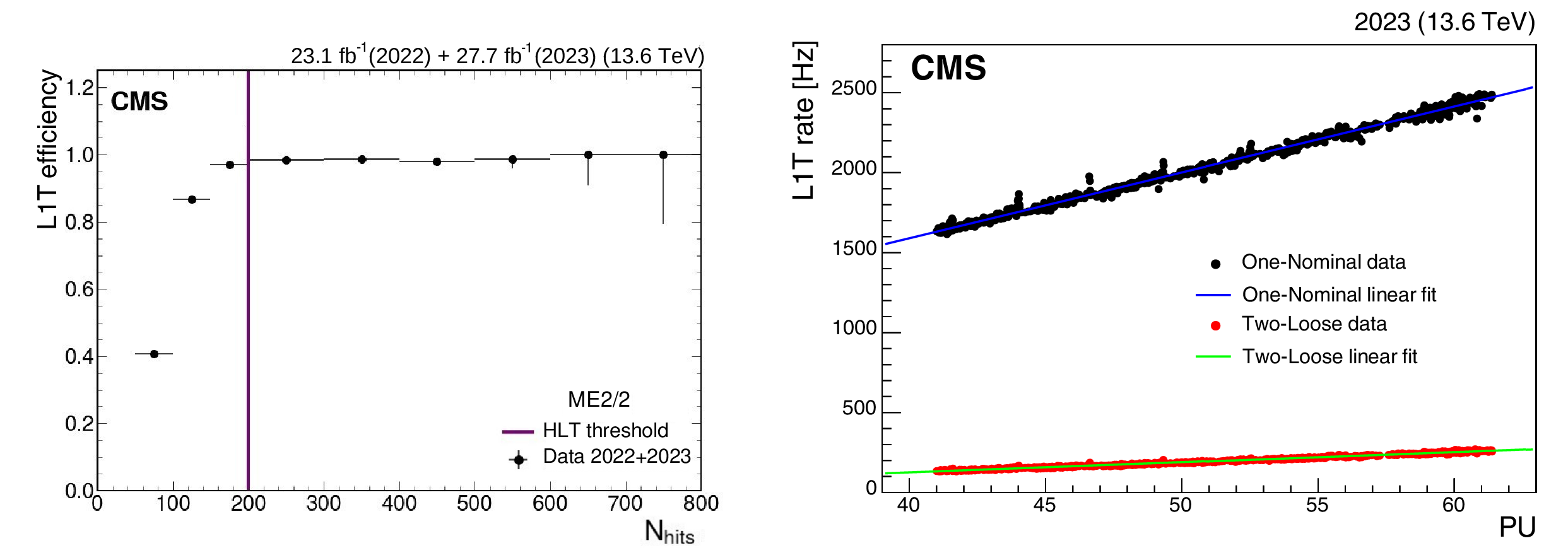

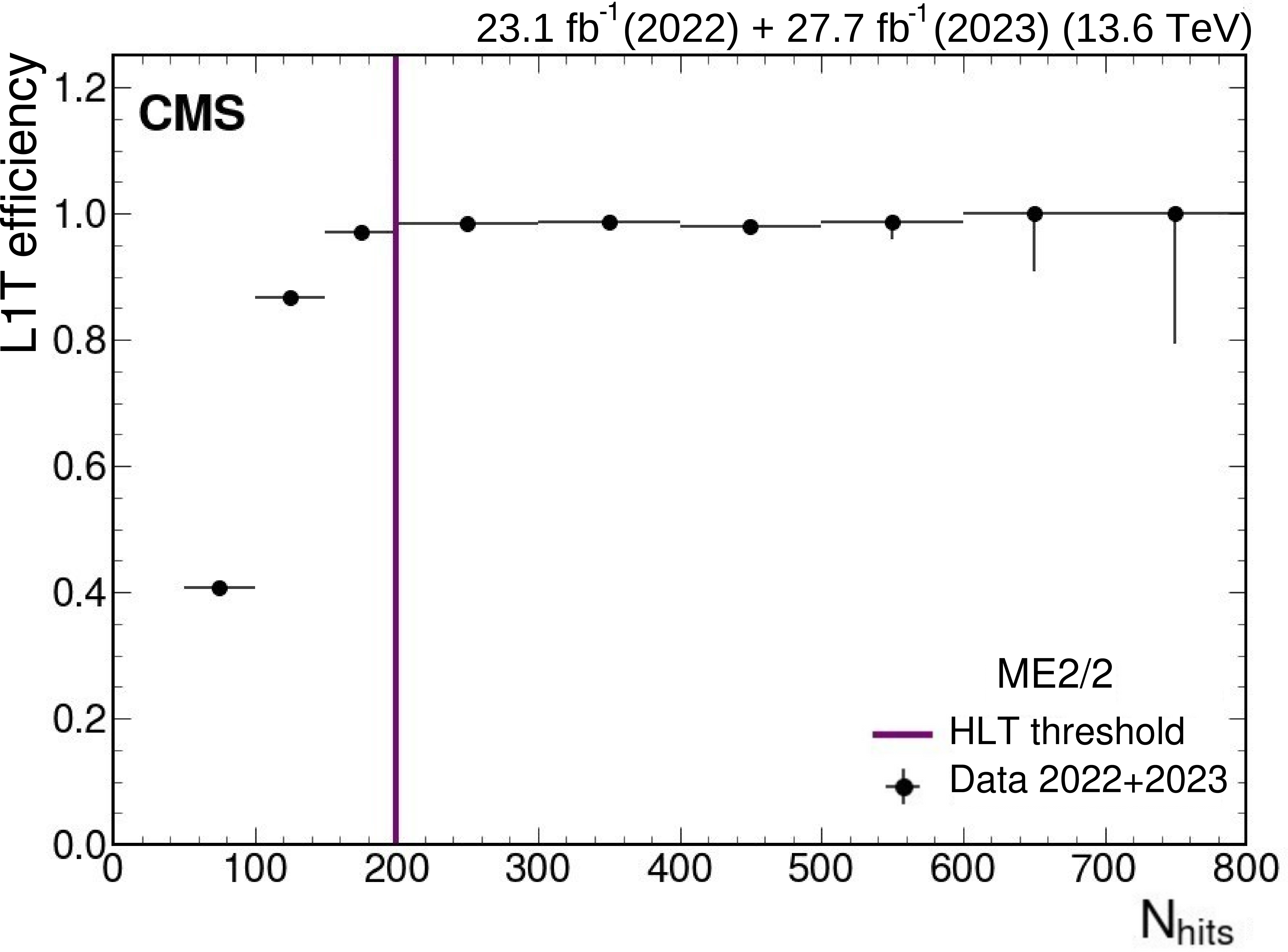

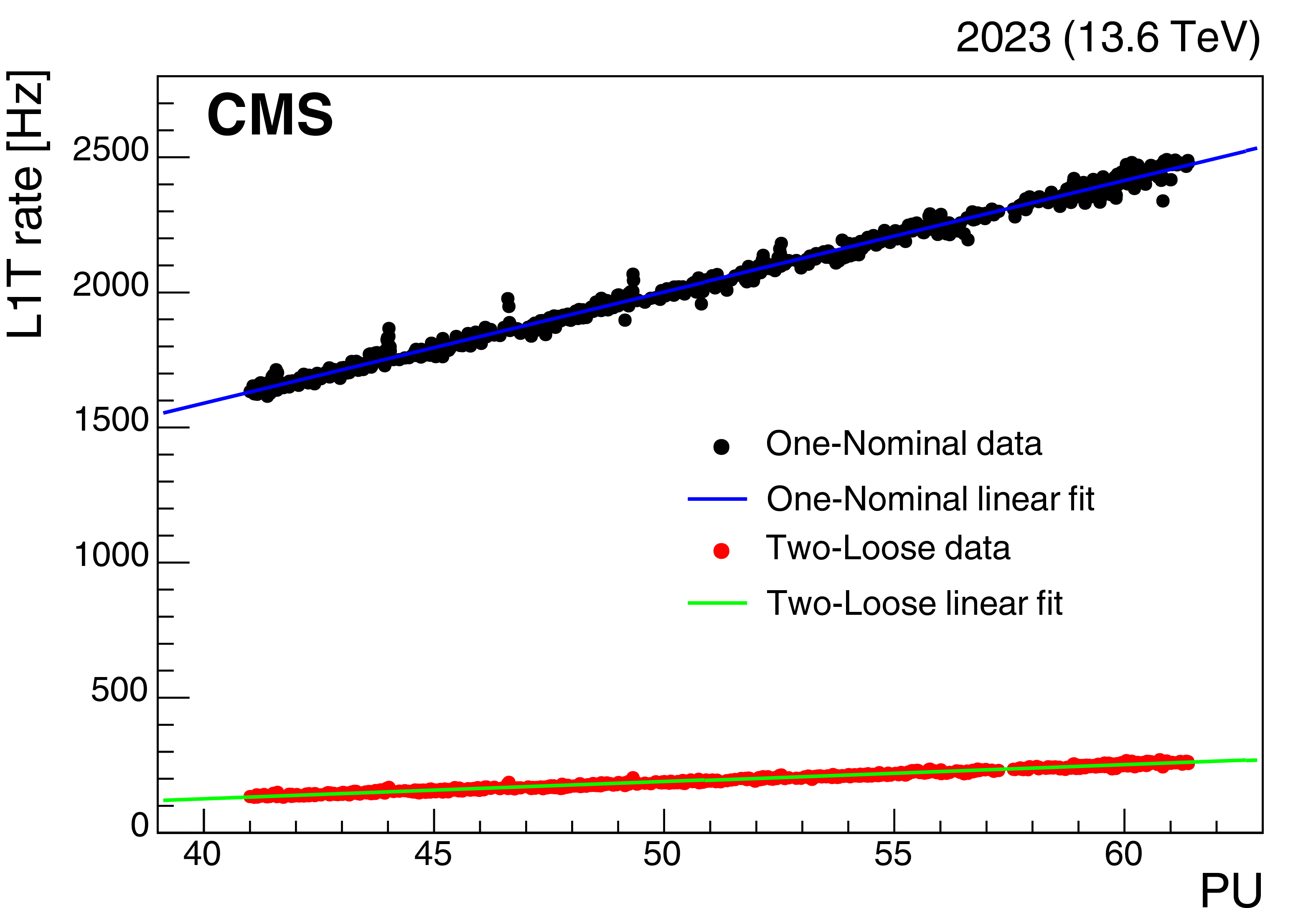

Figure 14:

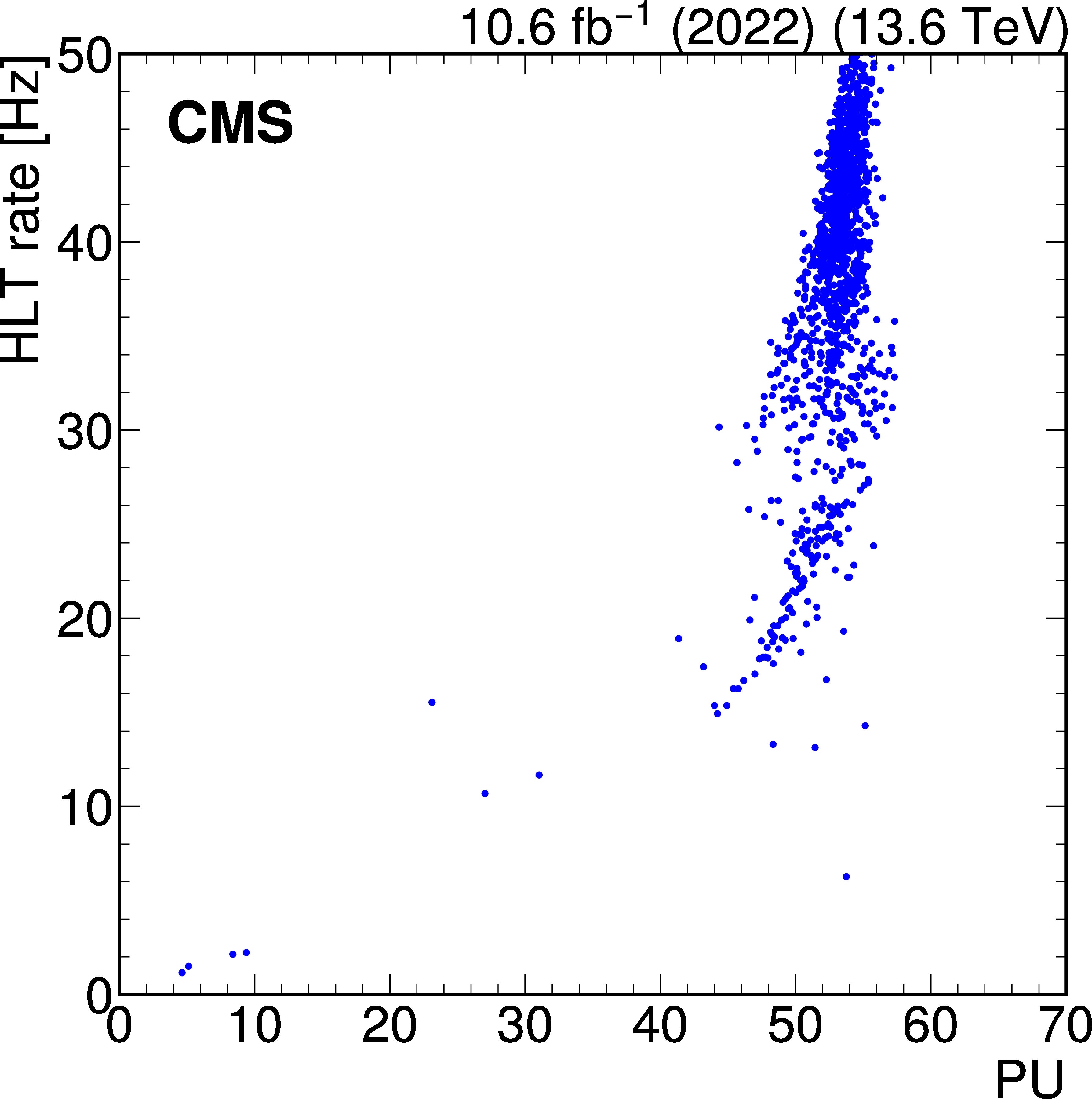

Total rate of the displaced $ \tau_\mathrm{h} $ trigger for a few representative runs in 2022 (left) and 2023 (right) data, as a function of PU. |

png pdf |

Figure 14-a:

Total rate of the displaced $ \tau_\mathrm{h} $ trigger for a few representative runs in 2022 (left) and 2023 (right) data, as a function of PU. |

png pdf |

Figure 14-b:

Total rate of the displaced $ \tau_\mathrm{h} $ trigger for a few representative runs in 2022 (left) and 2023 (right) data, as a function of PU. |

png pdf |

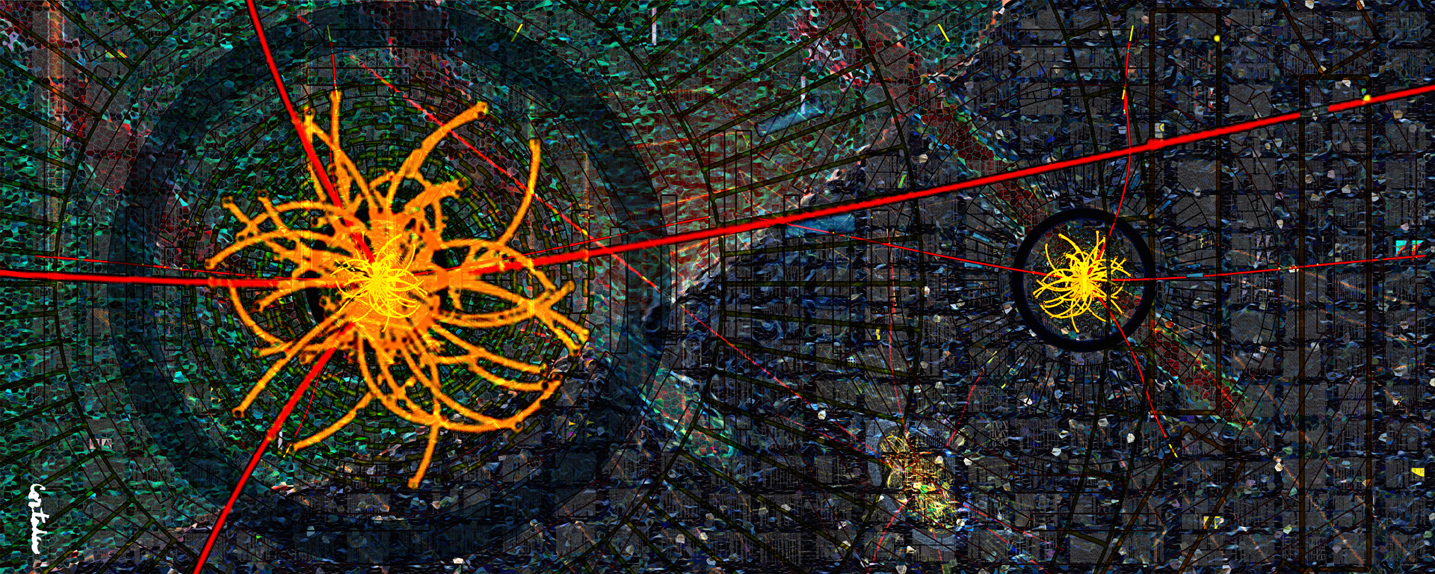

Figure 15:

Event display of a simulated pair of displaced jets arising from an LLP decay, producing displaced vertices and tracks. The simulated process is $ \mathrm{H} \to \text{S}\text{S} \to \mathrm{q}\overline{\mathrm{q}}\mathrm{q}\overline{\mathrm{q}} $. The blue curves indicate the reconstructed tracks. The yellow cones indicate two reconstructed jets, with a number of associated displaced tracks. The jets are reconstructed using the standard algorithms described in Section 4.5, which assume they originate from the PV. The blue point indicates the displaced vertex induced by the LLP decay. |

png pdf |

Figure 16:

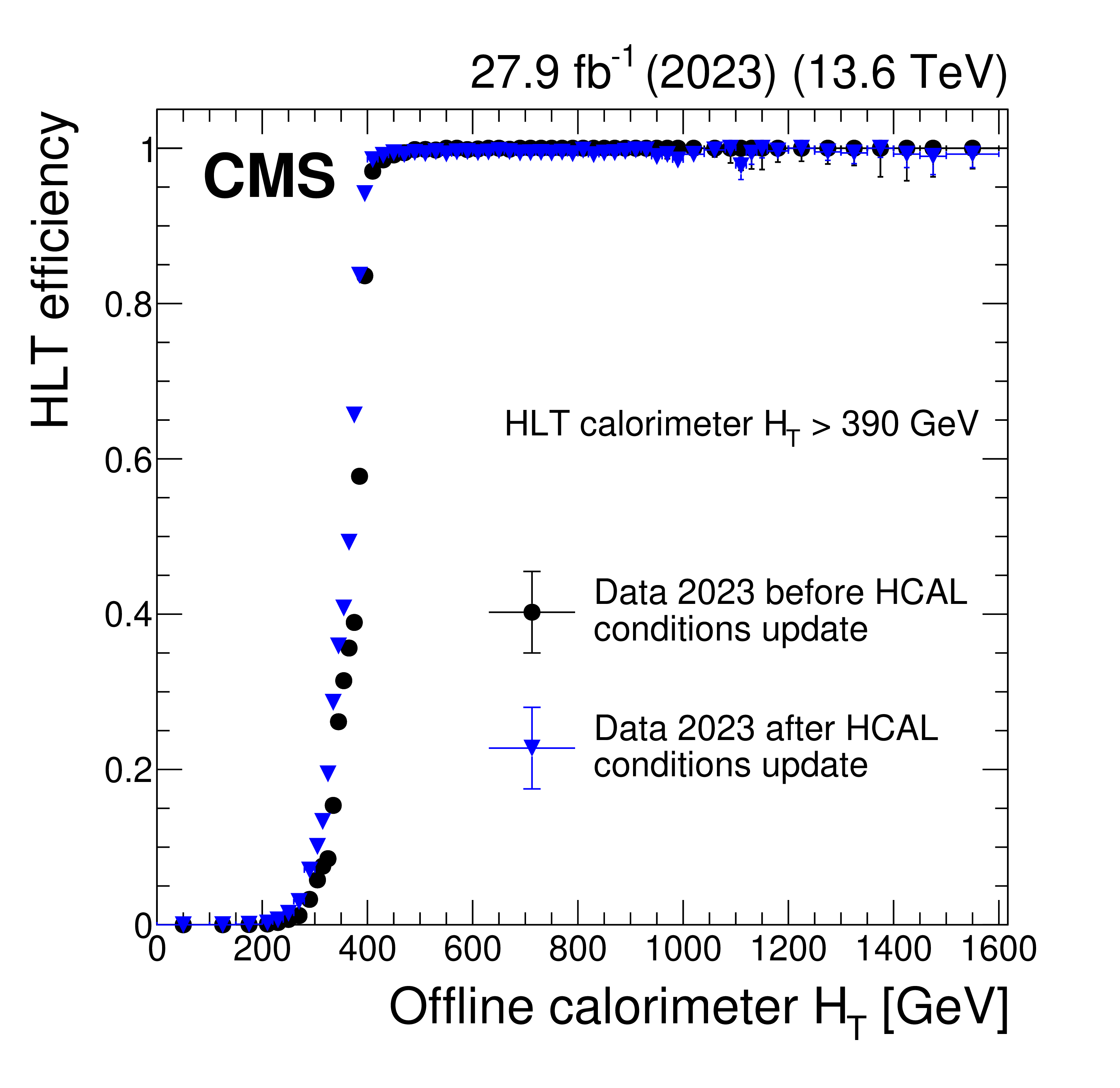

The HLT efficiency for a given event passing the main displaced-jet trigger to satisfy HLT calorimeter $ H_{\mathrm{T}} > $ 430 GeV (left) and $ H_{\mathrm{T}} > $ 390 GeV (right) as a function of the offline calorimeter $ H_{\mathrm{T}} $. For this trigger, the minimum calorimeter $ H_{\mathrm{T}} $ threshold was 430 $ (390) \text{Ge\hspace{-.08em}V} $ in 2022 (2023 and later). The measurements are performed with data collected in 2022 (green circles), in 2023 before an update of the HCAL gain values and energy response corrections (black squares), and in 2023 after the update (blue triangles). |

png pdf |

Figure 16-a:

The HLT efficiency for a given event passing the main displaced-jet trigger to satisfy HLT calorimeter $ H_{\mathrm{T}} > $ 430 GeV (left) and $ H_{\mathrm{T}} > $ 390 GeV (right) as a function of the offline calorimeter $ H_{\mathrm{T}} $. For this trigger, the minimum calorimeter $ H_{\mathrm{T}} $ threshold was 430 $ (390) \text{Ge\hspace{-.08em}V} $ in 2022 (2023 and later). The measurements are performed with data collected in 2022 (green circles), in 2023 before an update of the HCAL gain values and energy response corrections (black squares), and in 2023 after the update (blue triangles). |

png pdf |

Figure 16-b:

The HLT efficiency for a given event passing the main displaced-jet trigger to satisfy HLT calorimeter $ H_{\mathrm{T}} > $ 430 GeV (left) and $ H_{\mathrm{T}} > $ 390 GeV (right) as a function of the offline calorimeter $ H_{\mathrm{T}} $. For this trigger, the minimum calorimeter $ H_{\mathrm{T}} $ threshold was 430 $ (390) \text{Ge\hspace{-.08em}V} $ in 2022 (2023 and later). The measurements are performed with data collected in 2022 (green circles), in 2023 before an update of the HCAL gain values and energy response corrections (black squares), and in 2023 after the update (blue triangles). |

png pdf |

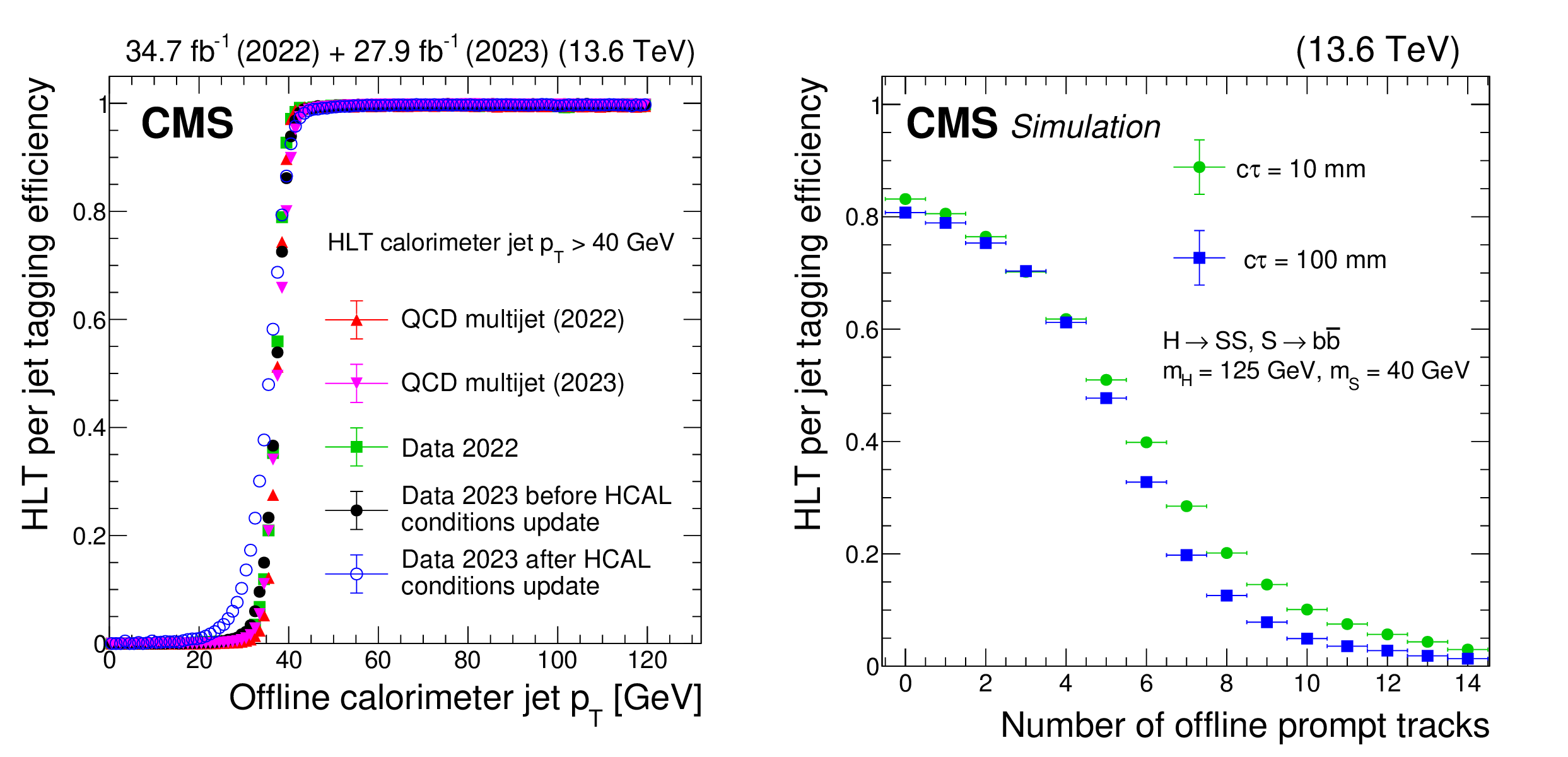

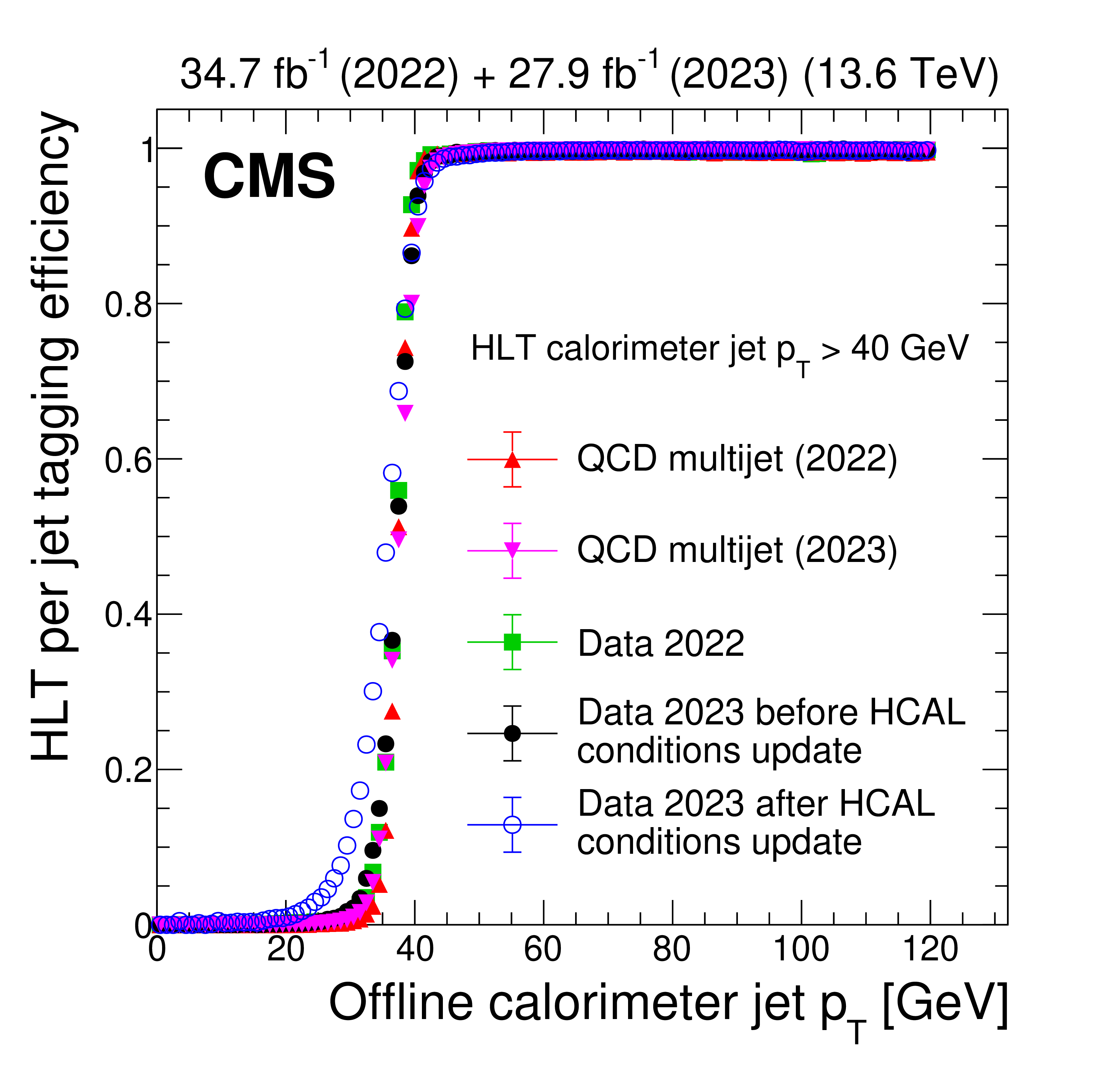

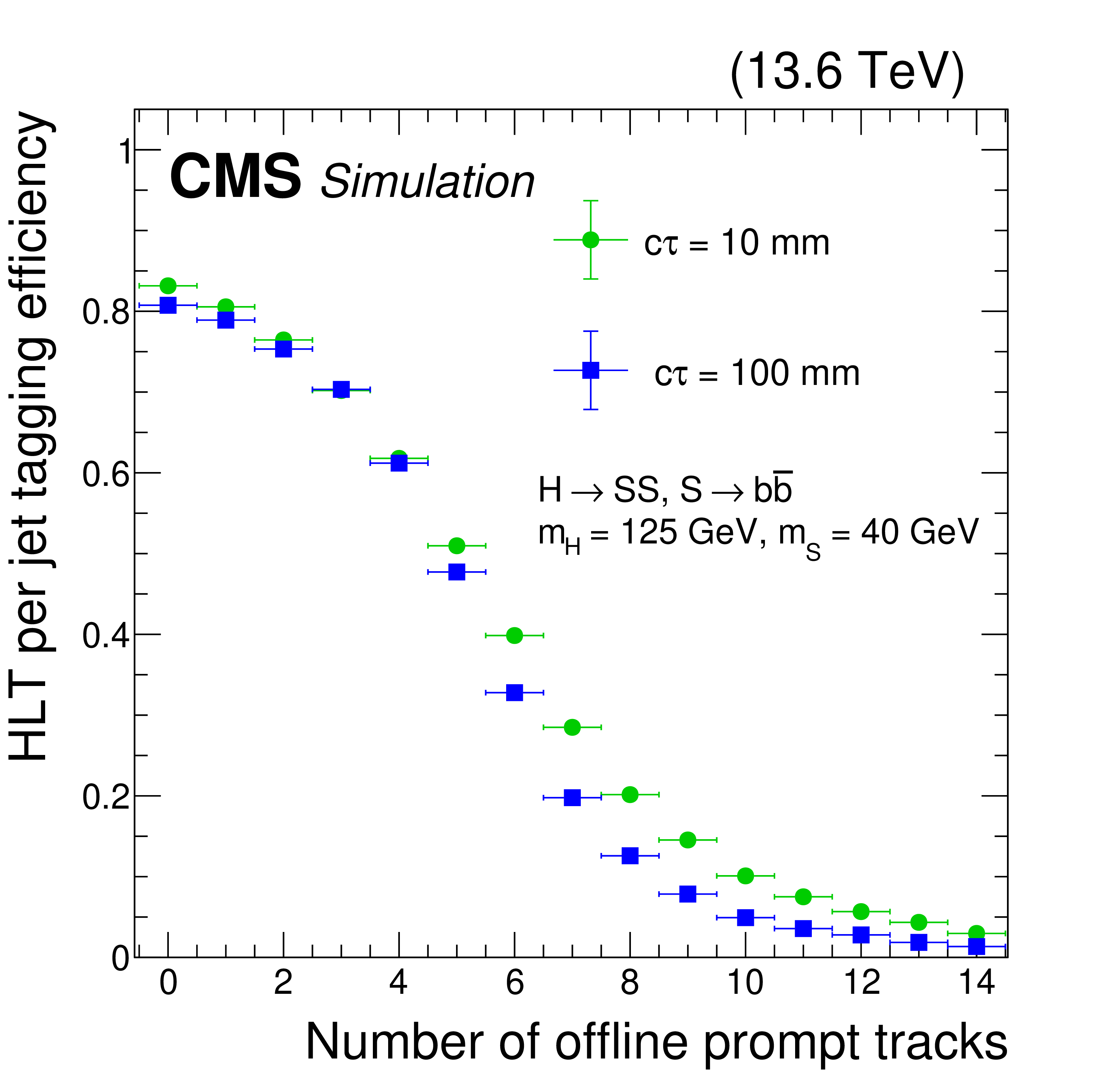

Figure 17:

The HLT efficiency of the main displaced-jet trigger: Efficiency of an offline calorimeter jet to (left) pass the online $ p_{\mathrm{T}} $ requirement in the displaced-jet triggers and (right) to have at most one HLT prompt track. In the left plot, the HLT calorimeter jets must have $ p_{\mathrm{T}} > $ 40 GeV. The efficiency is shown for data collected in 2022 (green squares), in 2023 before an update of the HCAL gains and energy response corrections (black filled circles), and in 2023 after the update (blue open circles). The efficiencies measured with QCD multijet simulations are also shown, for 2022 (red triangles) and 2023 (purple triangles) conditions. These measurements are performed using events collected with a prescaled trigger that requires $ H_{\mathrm{T}} > $ 425 GeV at the HLT. An offline $ H_{\mathrm{T}} > $ 450 GeV selection is also applied to ensure the prescaled trigger reaches its plateau. The efficiency is $ {>} 96% $ when the offline jet has $ p_{\mathrm{T}} > $ 40 GeV. The efficiency threshold is lower for the later 2023 data following updates to the HCAL energy corrections and readout gains, although the $ p_{\mathrm{T}} $ value at the start of the plateau is unchanged. The efficiency in the right plot is shown for 2022 conditions, as a function of the number of offline prompt tracks, in simulated $ \mathrm{H}\to\text{S}\text{S} $, $ \text{S}\to\mathrm{b}\overline{\mathrm{b}} $ signal events where $ m_{\mathrm{H}}= $ 125 GeV and $ m_{\text{S}}= $ 40 GeV. Two proper decay lengths of the $ \text{S} $ particle are shown: $ c\tau=10 \text{mm} $ (green circles) and $ c\tau=100 \text{mm} $ (blue squares). For jets in signal events, when the number of offline prompt tracks is $ {<} $ 4, the tagging efficiency is larger than 70%. |

png pdf |

Figure 17-a:

The HLT efficiency of the main displaced-jet trigger: Efficiency of an offline calorimeter jet to (left) pass the online $ p_{\mathrm{T}} $ requirement in the displaced-jet triggers and (right) to have at most one HLT prompt track. In the left plot, the HLT calorimeter jets must have $ p_{\mathrm{T}} > $ 40 GeV. The efficiency is shown for data collected in 2022 (green squares), in 2023 before an update of the HCAL gains and energy response corrections (black filled circles), and in 2023 after the update (blue open circles). The efficiencies measured with QCD multijet simulations are also shown, for 2022 (red triangles) and 2023 (purple triangles) conditions. These measurements are performed using events collected with a prescaled trigger that requires $ H_{\mathrm{T}} > $ 425 GeV at the HLT. An offline $ H_{\mathrm{T}} > $ 450 GeV selection is also applied to ensure the prescaled trigger reaches its plateau. The efficiency is $ {>} 96% $ when the offline jet has $ p_{\mathrm{T}} > $ 40 GeV. The efficiency threshold is lower for the later 2023 data following updates to the HCAL energy corrections and readout gains, although the $ p_{\mathrm{T}} $ value at the start of the plateau is unchanged. The efficiency in the right plot is shown for 2022 conditions, as a function of the number of offline prompt tracks, in simulated $ \mathrm{H}\to\text{S}\text{S} $, $ \text{S}\to\mathrm{b}\overline{\mathrm{b}} $ signal events where $ m_{\mathrm{H}}= $ 125 GeV and $ m_{\text{S}}= $ 40 GeV. Two proper decay lengths of the $ \text{S} $ particle are shown: $ c\tau=10 \text{mm} $ (green circles) and $ c\tau=100 \text{mm} $ (blue squares). For jets in signal events, when the number of offline prompt tracks is $ {<} $ 4, the tagging efficiency is larger than 70%. |

png pdf |

Figure 17-b:

The HLT efficiency of the main displaced-jet trigger: Efficiency of an offline calorimeter jet to (left) pass the online $ p_{\mathrm{T}} $ requirement in the displaced-jet triggers and (right) to have at most one HLT prompt track. In the left plot, the HLT calorimeter jets must have $ p_{\mathrm{T}} > $ 40 GeV. The efficiency is shown for data collected in 2022 (green squares), in 2023 before an update of the HCAL gains and energy response corrections (black filled circles), and in 2023 after the update (blue open circles). The efficiencies measured with QCD multijet simulations are also shown, for 2022 (red triangles) and 2023 (purple triangles) conditions. These measurements are performed using events collected with a prescaled trigger that requires $ H_{\mathrm{T}} > $ 425 GeV at the HLT. An offline $ H_{\mathrm{T}} > $ 450 GeV selection is also applied to ensure the prescaled trigger reaches its plateau. The efficiency is $ {>} 96% $ when the offline jet has $ p_{\mathrm{T}} > $ 40 GeV. The efficiency threshold is lower for the later 2023 data following updates to the HCAL energy corrections and readout gains, although the $ p_{\mathrm{T}} $ value at the start of the plateau is unchanged. The efficiency in the right plot is shown for 2022 conditions, as a function of the number of offline prompt tracks, in simulated $ \mathrm{H}\to\text{S}\text{S} $, $ \text{S}\to\mathrm{b}\overline{\mathrm{b}} $ signal events where $ m_{\mathrm{H}}= $ 125 GeV and $ m_{\text{S}}= $ 40 GeV. Two proper decay lengths of the $ \text{S} $ particle are shown: $ c\tau=10 \text{mm} $ (green circles) and $ c\tau=100 \text{mm} $ (blue squares). For jets in signal events, when the number of offline prompt tracks is $ {<} $ 4, the tagging efficiency is larger than 70%. |

png pdf |

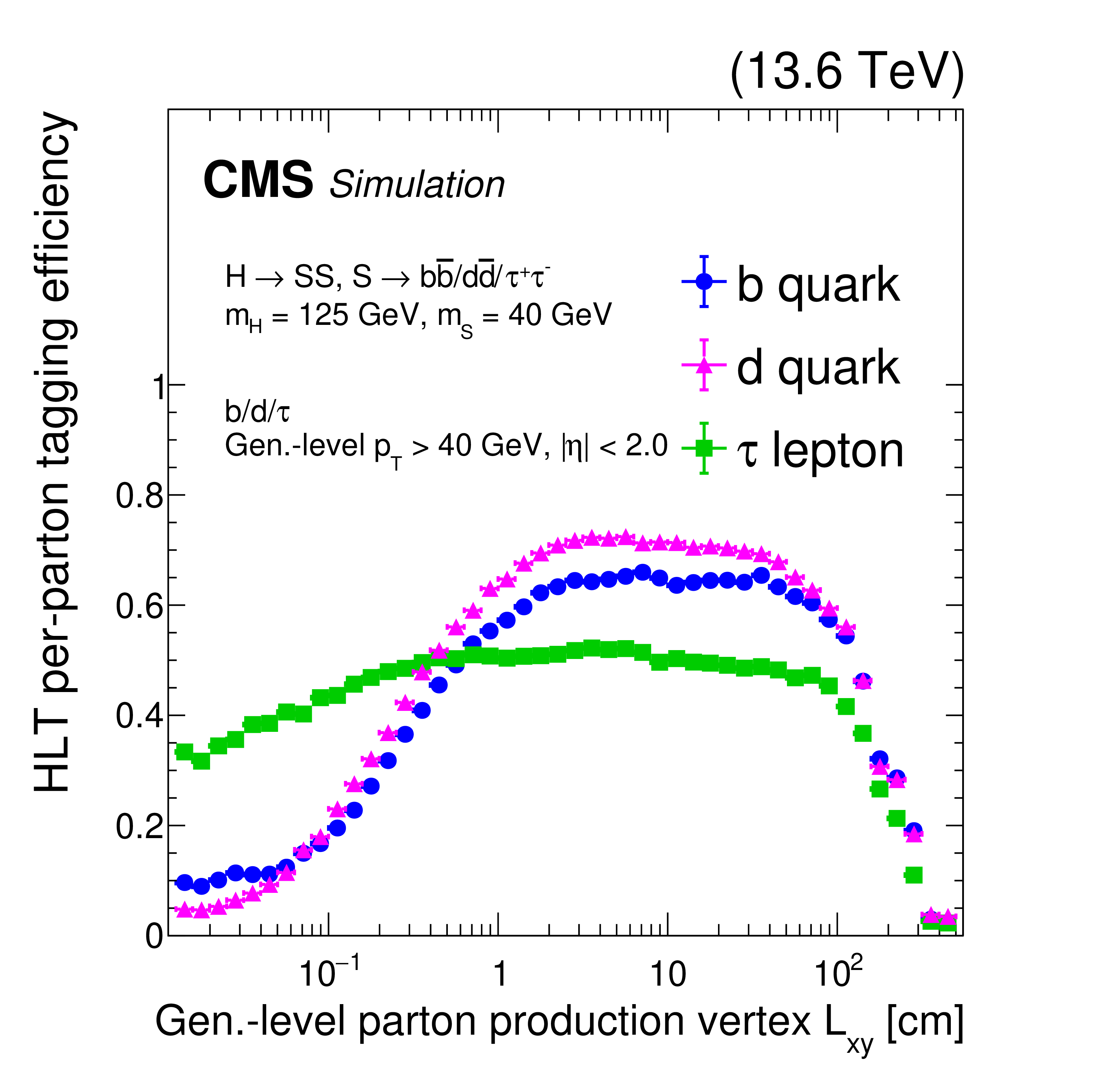

Figure 18:

The HLT efficiency of the main displaced-jet trigger for 2022 conditions, for $ \mathrm{H}\to\text{S}\text{S} $ signal events where $ m_{\mathrm{H}}= $ 125 GeV and $ m_{\text{S}}= $ 40 GeV. The per-parton (quark or lepton) HLT displaced-jet tagging efficiency as a function of the generator-level $ L_{\text{xy}} $ of the parton is shown for displaced b quarks (blue circles), d quarks (purple triangles), and $ \tau $ leptons (green squares) with $ p_{\mathrm{T}} > $ 40 GeV and $ |\eta| < $ 2.0. Events are required to satisfy the HLT $ H_{\mathrm{T}} > $ 430 GeV requirement. |

png pdf |

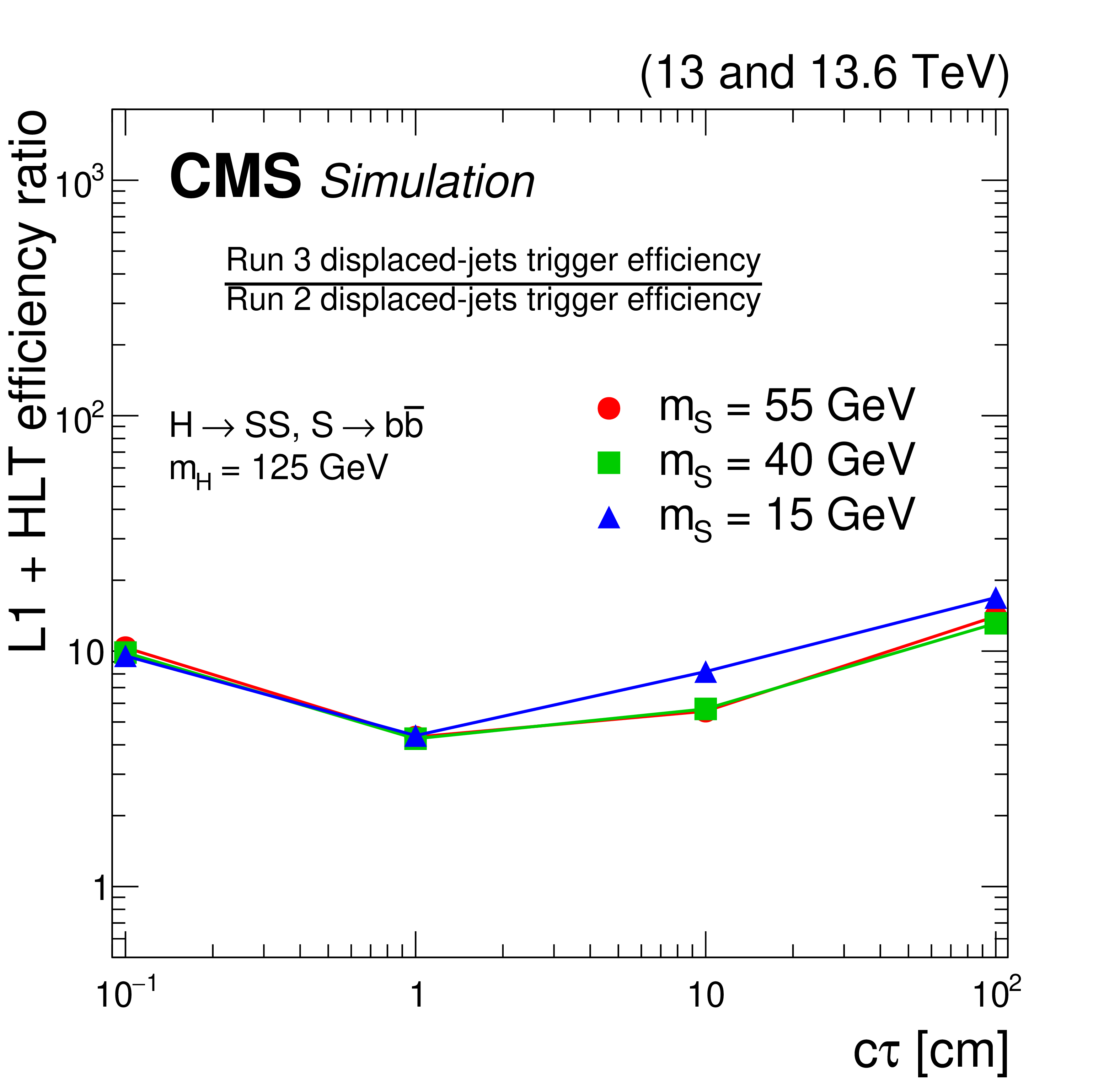

Figure 19:

The ratio between the Run 3 displaced-jet trigger efficiency and the Run 2 displaced-jet trigger efficiency as a function of LLP $ c\tau $, in simulated $ \mathrm{H}\to\text{S}\text{S} $, $ \text{S}\to\mathrm{b}\overline{\mathrm{b}} $ signal events where $ m_{\mathrm{H}}= $ 125 GeV and $ m_{\text{S}}= $ 15 (blue triangles), 40 (green squares), or 55 (red circles) GeV. The Run 3 displaced-jet trigger efficiencies are measured for 2022 conditions. |

png pdf |

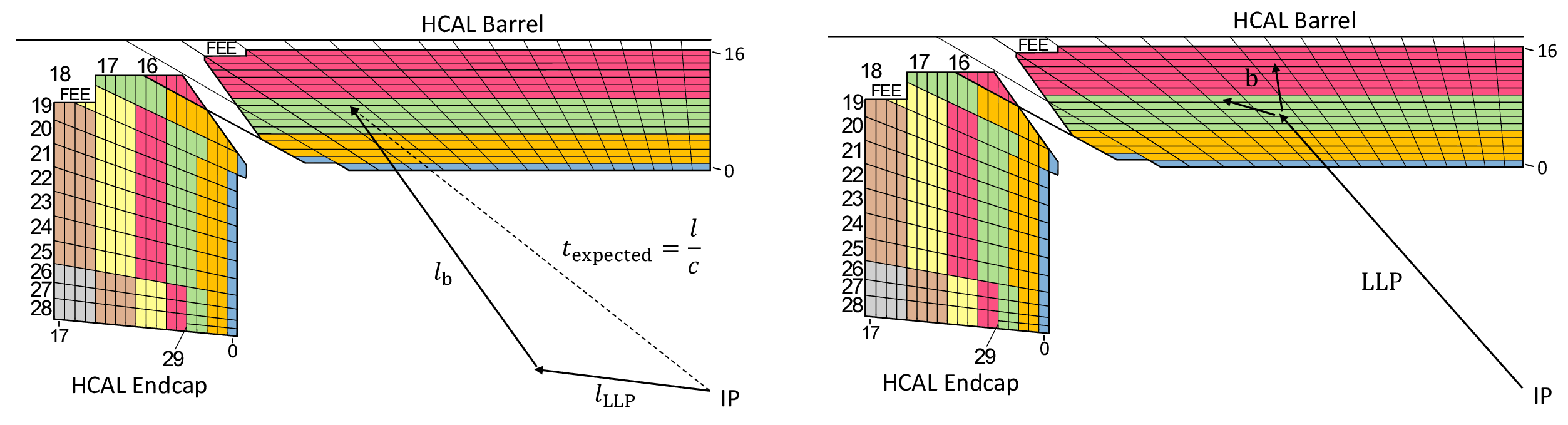

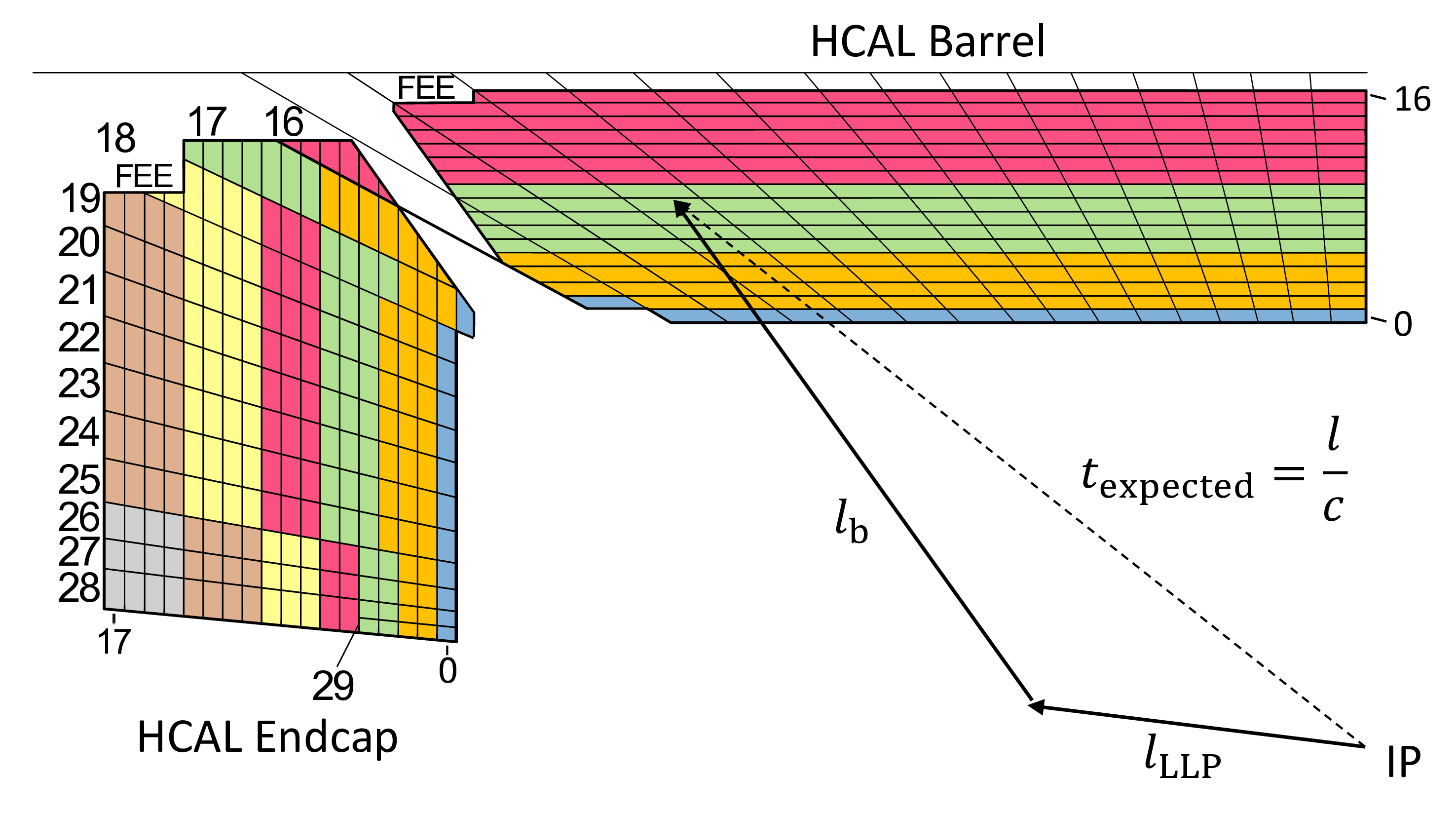

Figure 20:

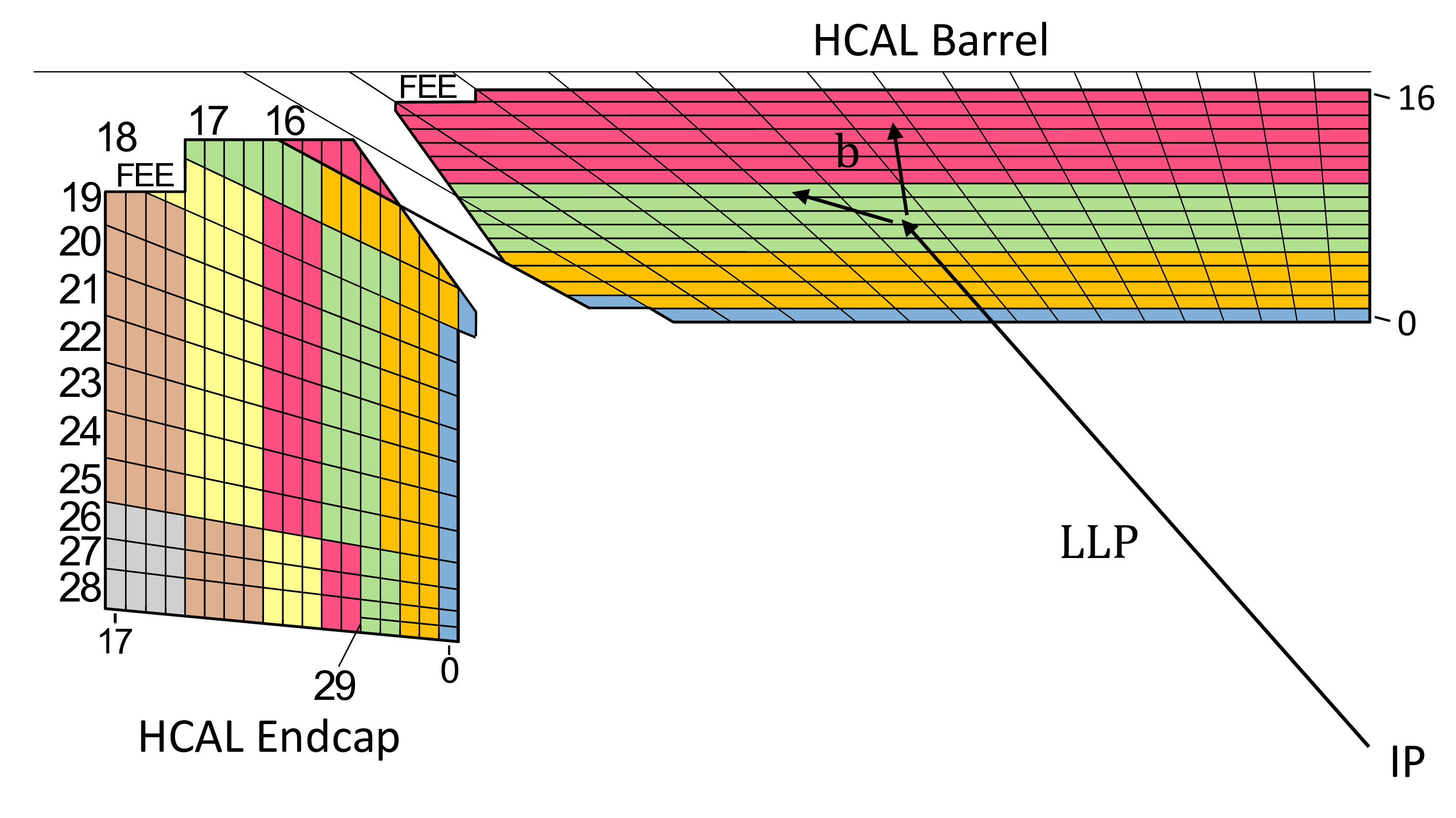

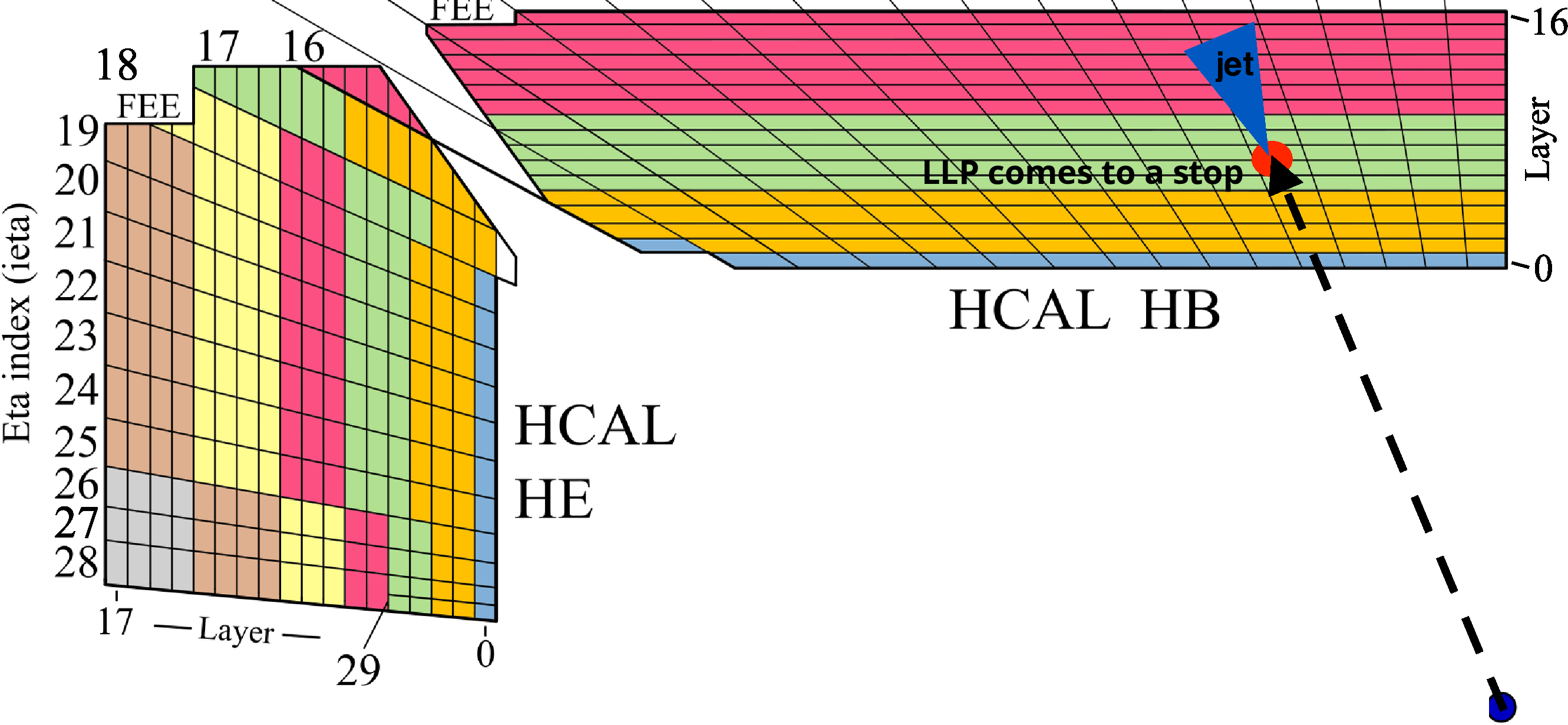

Diagram showing the lateral view of a quadrant of the CMS HCAL barrel and endcap in Run 3. The distinct depth segmentation is indicated by the different colors, where the HCAL barrel consists of 4 depths and the HCAL endcap has up to 7 depths. A delayed-jet signature is shown (left), where the time delay results from a combination of the low LLP velocity because of its relatively high mass and the path length difference with respect to a promptly decaying particle. A time delay consists of the path length difference between a particle traveling from the IP directly to the calorimeter ($ l $), as compared to the LLP path ($ l_{\text{LLP}} $) plus the b quark path ($ l_{\mathrm{b}} $). Additionally, the LLP may also have a significantly lower velocity, while other particles are assumed in this example to be highly relativistic. Thus, the difference in time of arrival at the calorimeter is $ \Delta t = \frac{l_{\text{LLP}}}{v_{\text{LLP}}} + \frac{l_{\mathrm{b}}}{c} - \frac{l}{c} $. A displaced-jet signature is also depicted (right), resulting from an LLP decaying within the HCAL volume to produce significant energy deposits deeper in the HCAL with minimal energy deposits in shallower calorimeter layers. |

png pdf |

Figure 20-a:

Diagram showing the lateral view of a quadrant of the CMS HCAL barrel and endcap in Run 3. The distinct depth segmentation is indicated by the different colors, where the HCAL barrel consists of 4 depths and the HCAL endcap has up to 7 depths. A delayed-jet signature is shown (left), where the time delay results from a combination of the low LLP velocity because of its relatively high mass and the path length difference with respect to a promptly decaying particle. A time delay consists of the path length difference between a particle traveling from the IP directly to the calorimeter ($ l $), as compared to the LLP path ($ l_{\text{LLP}} $) plus the b quark path ($ l_{\mathrm{b}} $). Additionally, the LLP may also have a significantly lower velocity, while other particles are assumed in this example to be highly relativistic. Thus, the difference in time of arrival at the calorimeter is $ \Delta t = \frac{l_{\text{LLP}}}{v_{\text{LLP}}} + \frac{l_{\mathrm{b}}}{c} - \frac{l}{c} $. A displaced-jet signature is also depicted (right), resulting from an LLP decaying within the HCAL volume to produce significant energy deposits deeper in the HCAL with minimal energy deposits in shallower calorimeter layers. |

png pdf |

Figure 20-b:

Diagram showing the lateral view of a quadrant of the CMS HCAL barrel and endcap in Run 3. The distinct depth segmentation is indicated by the different colors, where the HCAL barrel consists of 4 depths and the HCAL endcap has up to 7 depths. A delayed-jet signature is shown (left), where the time delay results from a combination of the low LLP velocity because of its relatively high mass and the path length difference with respect to a promptly decaying particle. A time delay consists of the path length difference between a particle traveling from the IP directly to the calorimeter ($ l $), as compared to the LLP path ($ l_{\text{LLP}} $) plus the b quark path ($ l_{\mathrm{b}} $). Additionally, the LLP may also have a significantly lower velocity, while other particles are assumed in this example to be highly relativistic. Thus, the difference in time of arrival at the calorimeter is $ \Delta t = \frac{l_{\text{LLP}}}{v_{\text{LLP}}} + \frac{l_{\mathrm{b}}}{c} - \frac{l}{c} $. A displaced-jet signature is also depicted (right), resulting from an LLP decaying within the HCAL volume to produce significant energy deposits deeper in the HCAL with minimal energy deposits in shallower calorimeter layers. |

png pdf |

Figure 21:

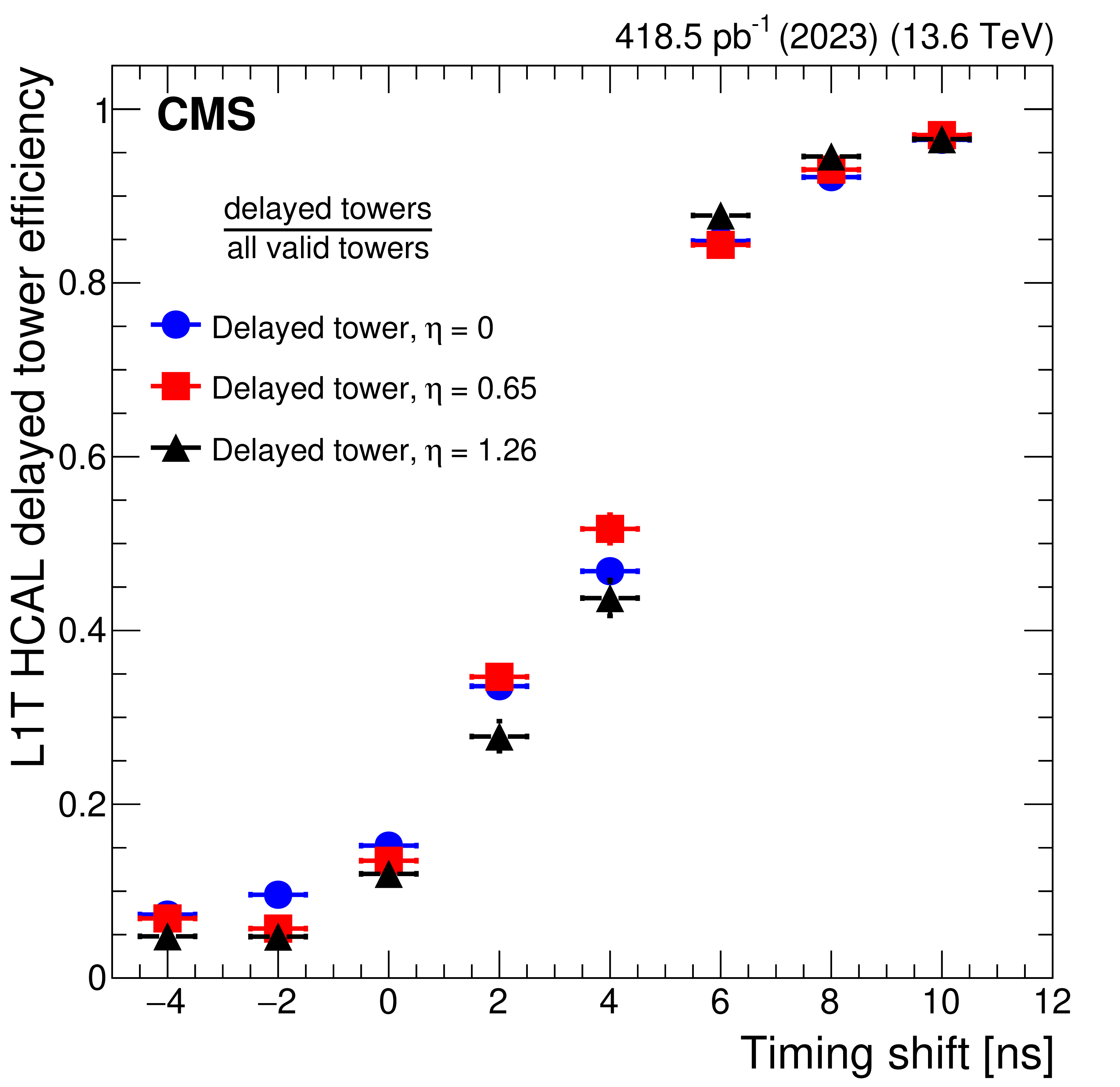

The L1T HCAL trigger tower efficiency of the delayed timing towers in the 2023 HCAL timing-scan data, with efficiencies split by trigger towers centered at $ \eta\approx $ 0 (blue circles), 0.65 (red squares), 1.26 (black triangles), and with width $ \Delta \eta = $ 0.087. The sharp rise in efficiency between timing delays of 0--6\unitns is expected, as the prompt timing range includes pulses up to and including those recorded at a 6\unitns arrival time (digitized in half-ns steps by the TDC), demonstrating the timing trigger performance. The delayed timing towers must have at least one delayed cell, no prompt cells, and energy $ {>} $ 4 GeV. The efficiency is calculated relative to towers with any valid timing code, meaning the tower contains at least one cell with energy $ {>} $ 4 GeV and a TDC code of prompt, slightly delayed, or very delayed. Multiple delayed or displaced towers are required for the HCAL-based displaced- and delayed-jet L1T to pass. |

png pdf |

Figure 22:

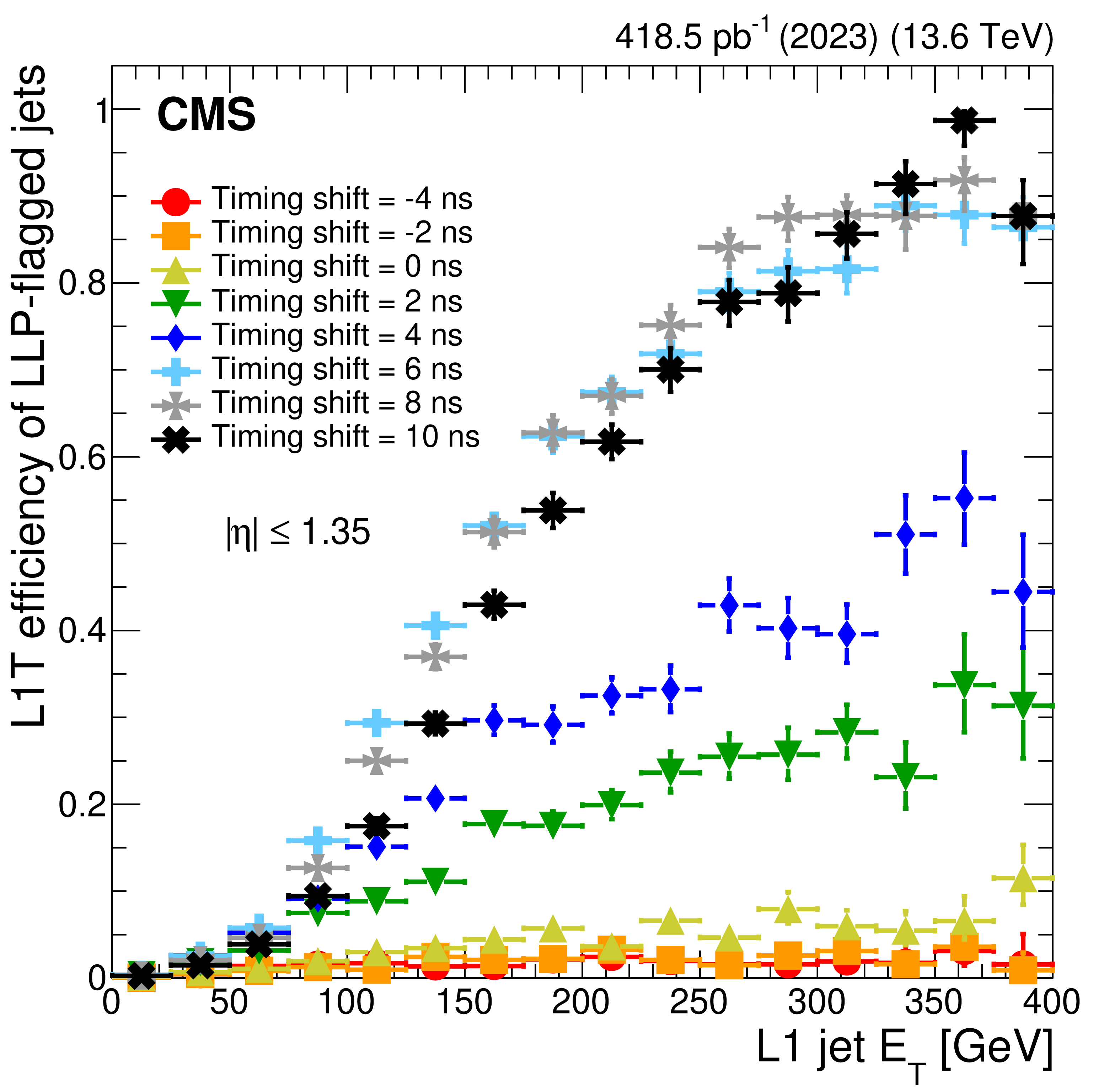

The L1T efficiency of the LLP jet trigger in 2023 HCAL timing-scan data as a function of L1 jet $ E_{\mathrm{T}} $. The results are inclusive in $ \eta $ for the HCAL barrel, corresponding to $ |\eta| < $ 1.35. The fraction of LLP-flagged L1 jets is compared to all L1 jets from a data set of events enriched in jets or $ p_{\mathrm{T}}^\text{miss} $. No explicit selection criterion is applied on the jet $ E_{\mathrm{T}} $, though the implicit requirement for a jet to have at least two cells with $ E_{\mathrm{T}} > $ 4 GeV shapes the resulting jet trigger efficiency curve. While the trigger configuration is based on the presence of both delayed and displaced towers, the timing scan demonstrates the ability of the trigger to select delayed jets only. |

png pdf |

Figure 23:

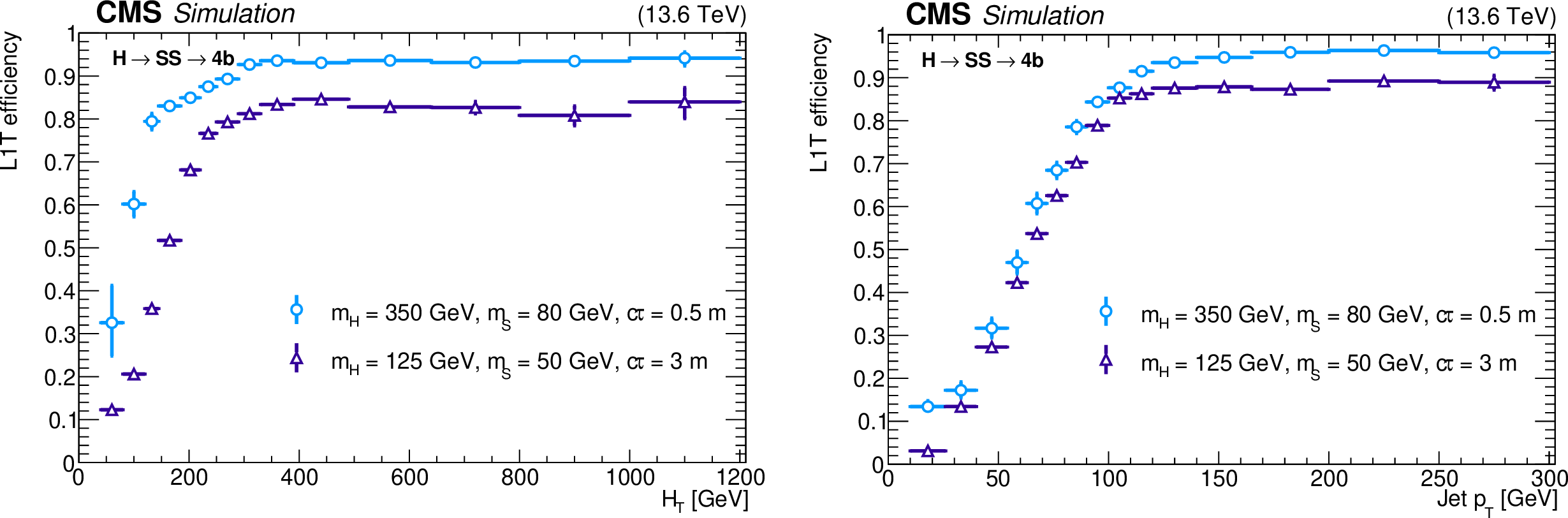

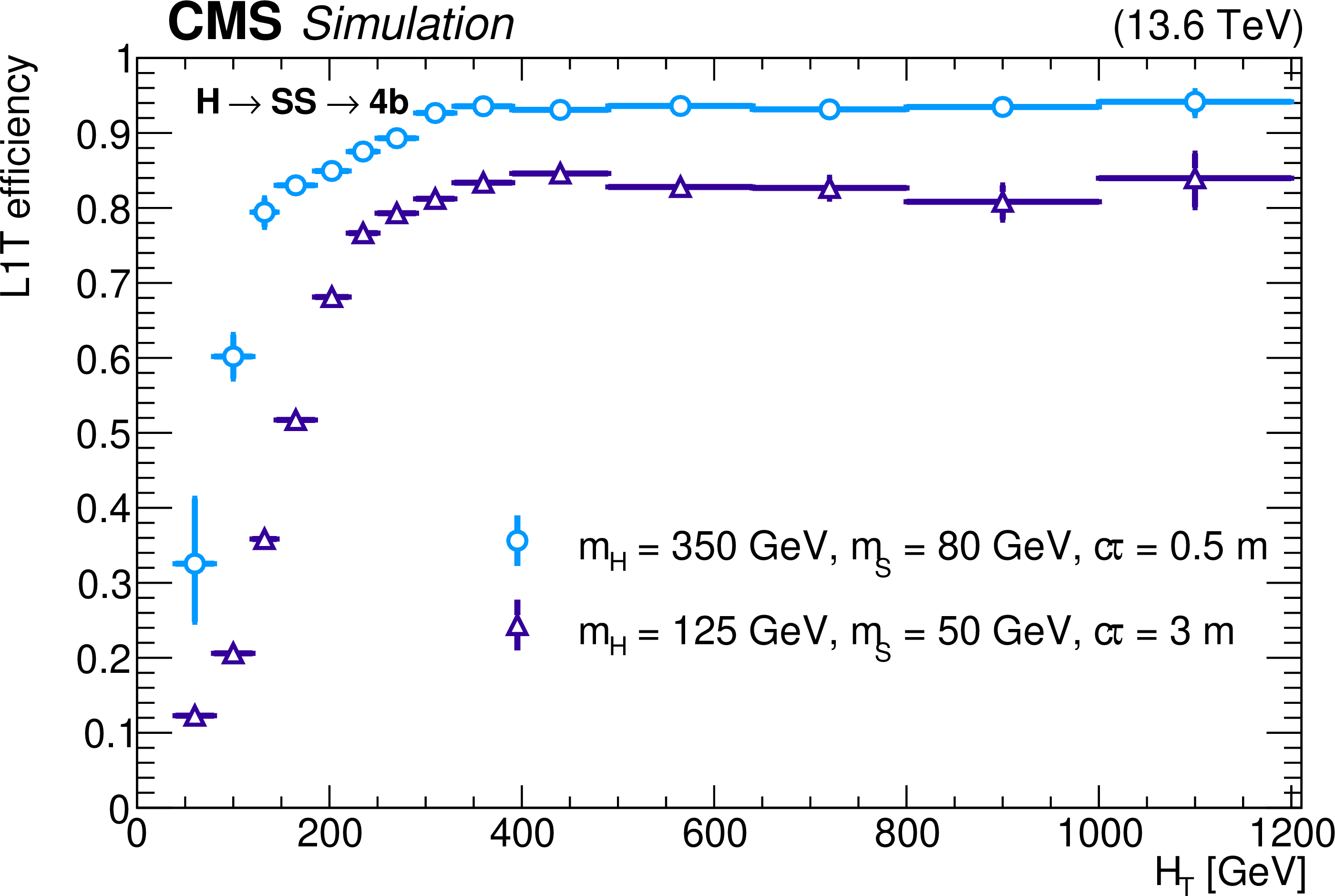

The L1T efficiency of the HCAL-based LLP jet triggers, as a function of event $ H_{\mathrm{T}} $ (left) and jet $ p_{\mathrm{T}} $ (right), for $ \mathrm{H} \to \text{S}\text{S} \to \mathrm{b}\overline{\mathrm{b}}\mathrm{b}\overline{\mathrm{b}} $ events with $ m_{\mathrm{H}}= $ 350 GeV, $ m_{\text{S}}= $ 80 GeV, and $ c\tau_{\text{S}}= $ 0.5 m (light blue circles) and $ m_{\mathrm{H}}= $ 125 GeV, $ m_{\text{S}}= $ 50 GeV, and $ c\tau_{\text{S}}= $ 3 m (purple triangles), for 2023 conditions. The trigger efficiency is evaluated for LLPs decaying in HB depths 3 or 4, corresponding to 214.2 $ < R < 295 \text{cm} $ and $ |\eta| < $ 1.26. These LLPs are also required to be matched to an offline jet with $ p_{\mathrm{T}} > $ 40 GeV in HB. |

png pdf |

Figure 23-a:

The L1T efficiency of the HCAL-based LLP jet triggers, as a function of event $ H_{\mathrm{T}} $ (left) and jet $ p_{\mathrm{T}} $ (right), for $ \mathrm{H} \to \text{S}\text{S} \to \mathrm{b}\overline{\mathrm{b}}\mathrm{b}\overline{\mathrm{b}} $ events with $ m_{\mathrm{H}}= $ 350 GeV, $ m_{\text{S}}= $ 80 GeV, and $ c\tau_{\text{S}}= $ 0.5 m (light blue circles) and $ m_{\mathrm{H}}= $ 125 GeV, $ m_{\text{S}}= $ 50 GeV, and $ c\tau_{\text{S}}= $ 3 m (purple triangles), for 2023 conditions. The trigger efficiency is evaluated for LLPs decaying in HB depths 3 or 4, corresponding to 214.2 $ < R < 295 \text{cm} $ and $ |\eta| < $ 1.26. These LLPs are also required to be matched to an offline jet with $ p_{\mathrm{T}} > $ 40 GeV in HB. |

png pdf |

Figure 23-b:

The L1T efficiency of the HCAL-based LLP jet triggers, as a function of event $ H_{\mathrm{T}} $ (left) and jet $ p_{\mathrm{T}} $ (right), for $ \mathrm{H} \to \text{S}\text{S} \to \mathrm{b}\overline{\mathrm{b}}\mathrm{b}\overline{\mathrm{b}} $ events with $ m_{\mathrm{H}}= $ 350 GeV, $ m_{\text{S}}= $ 80 GeV, and $ c\tau_{\text{S}}= $ 0.5 m (light blue circles) and $ m_{\mathrm{H}}= $ 125 GeV, $ m_{\text{S}}= $ 50 GeV, and $ c\tau_{\text{S}}= $ 3 m (purple triangles), for 2023 conditions. The trigger efficiency is evaluated for LLPs decaying in HB depths 3 or 4, corresponding to 214.2 $ < R < 295 \text{cm} $ and $ |\eta| < $ 1.26. These LLPs are also required to be matched to an offline jet with $ p_{\mathrm{T}} > $ 40 GeV in HB. |

png pdf |

Figure 24:

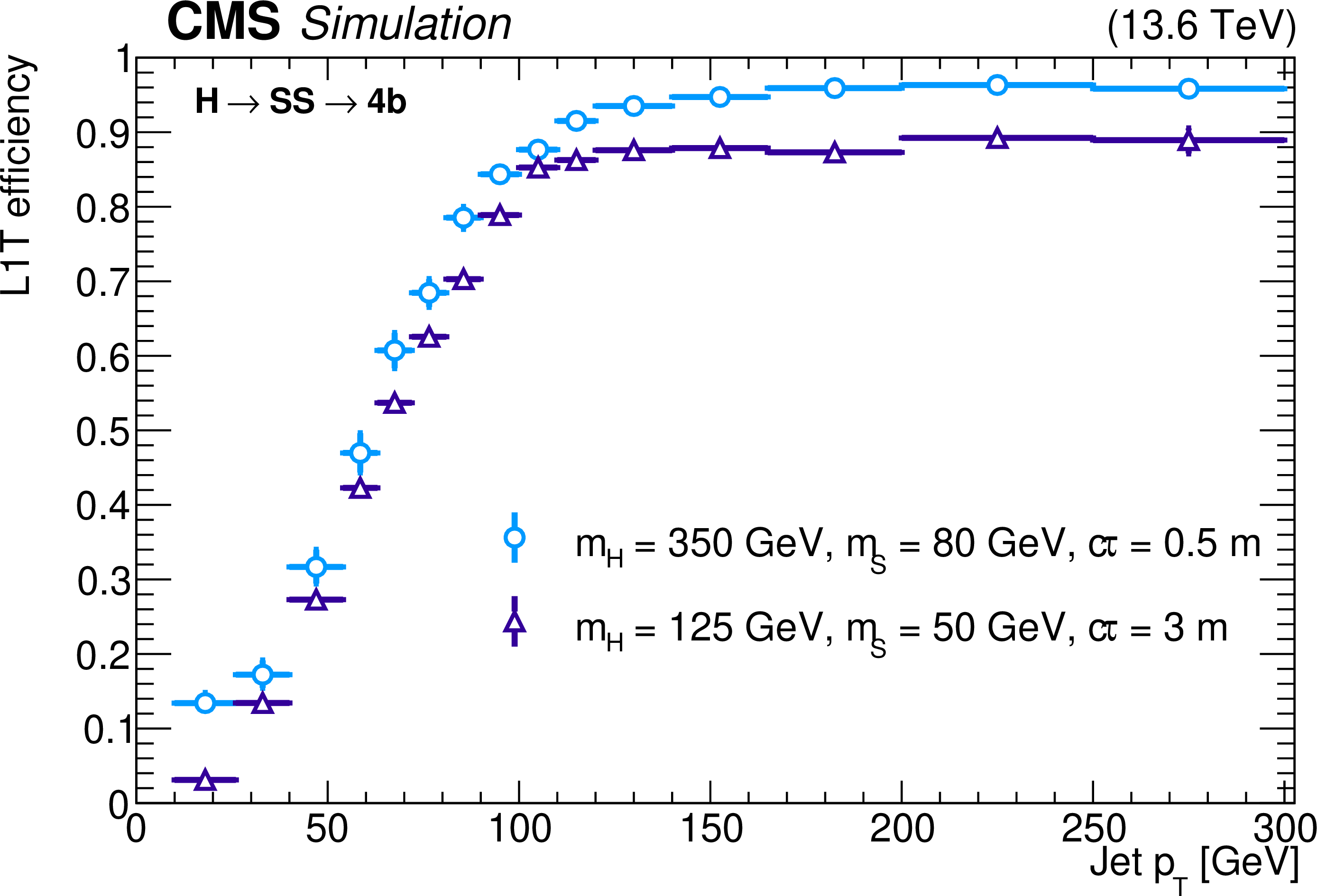

The L1T efficiency of the HCAL-based LLP jet triggers as a function of LLP decay radial position $ R $ for $ \mathrm{H} \to \text{S}\text{S} \to \mathrm{b}\overline{\mathrm{b}}\mathrm{b}\overline{\mathrm{b}} $ events with $ m_{\mathrm{H}}= $ 350 GeV, $ m_{\text{S}}= $ 80 GeV, and $ c\tau_{\text{S}}= $ 0.5 m (light blue circles) and $ m_{\mathrm{H}}= $ 125 GeV, $ m_{\text{S}}= $ 50 GeV, and $ c\tau_{\text{S}}= $ 3 m (purple triangles), for 2023 conditions. The trigger efficiency is evaluated for LLPs within $ |\eta| < $ 1.26 where either the LLP or its decay products are matched to an offline jet in HB with $ p_{\mathrm{T}} > $ 100 GeV. |

png pdf |

Figure 25:

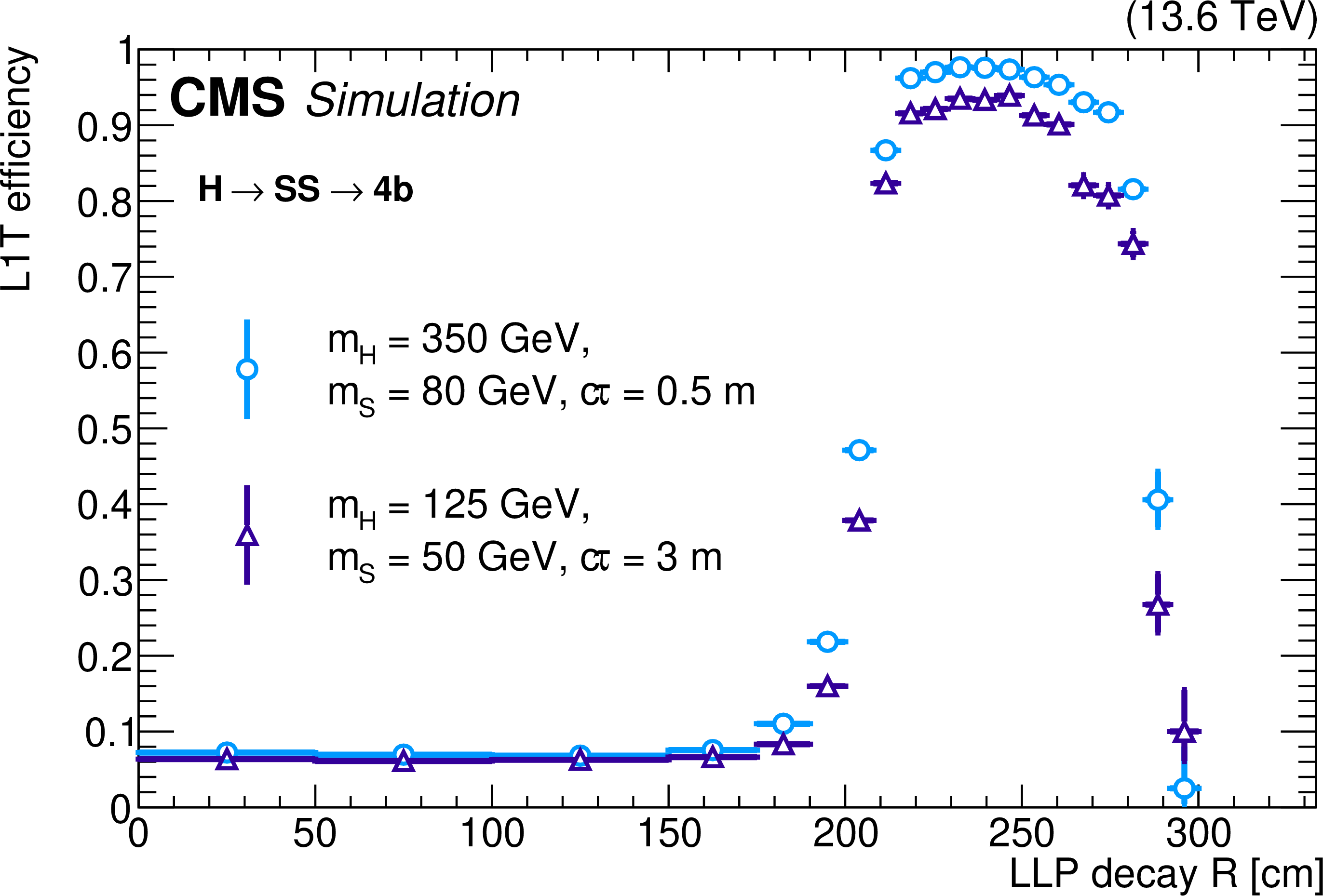

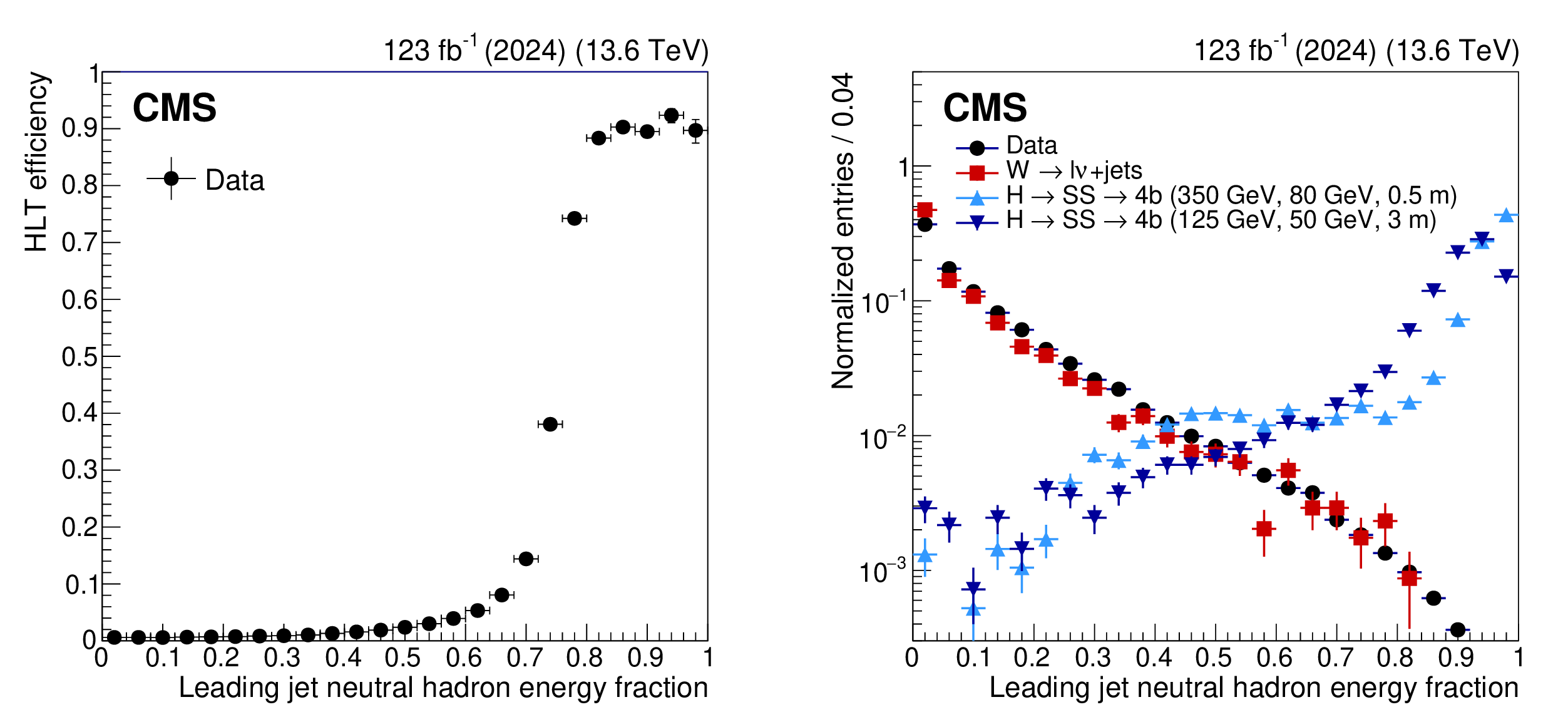

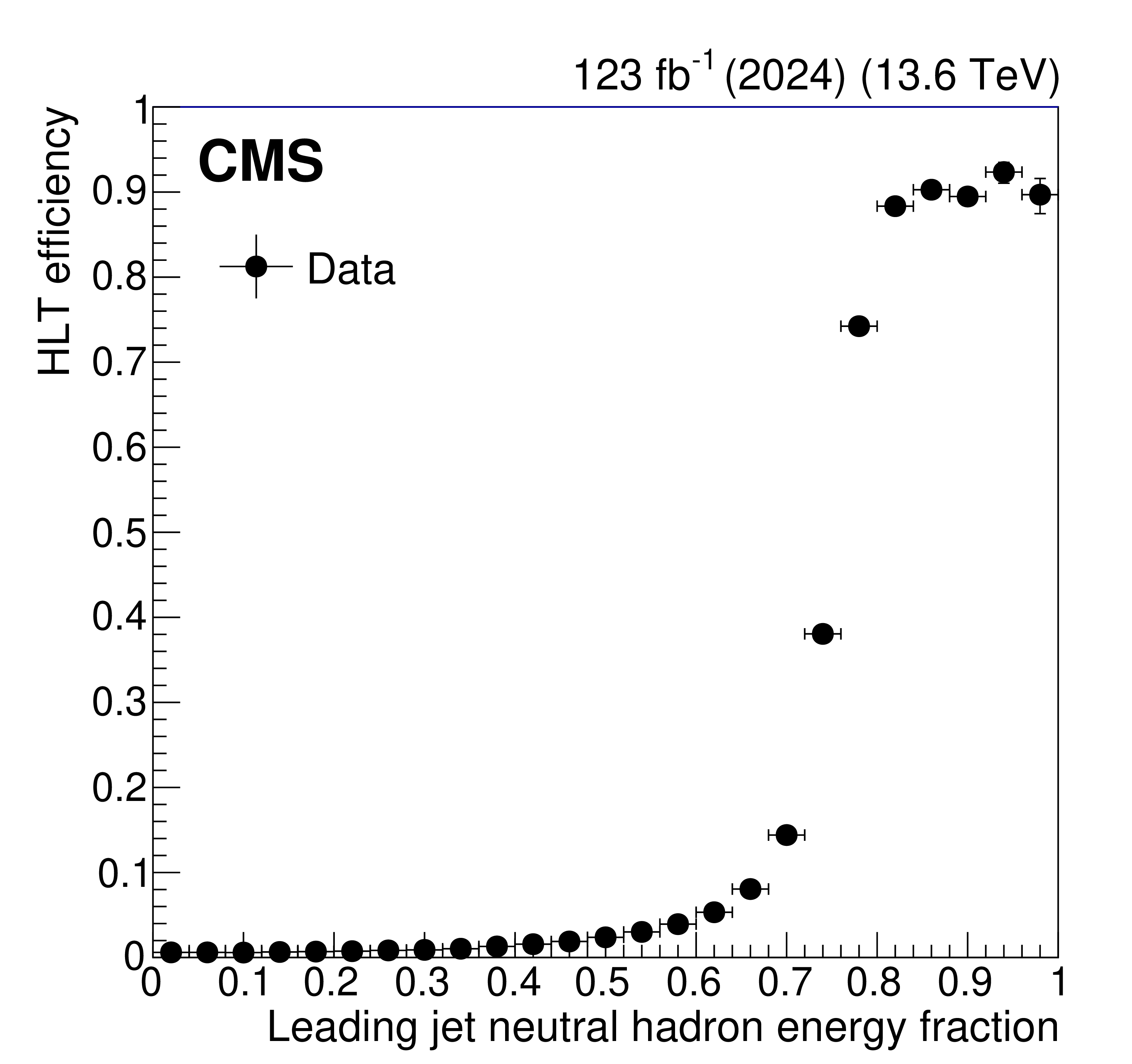

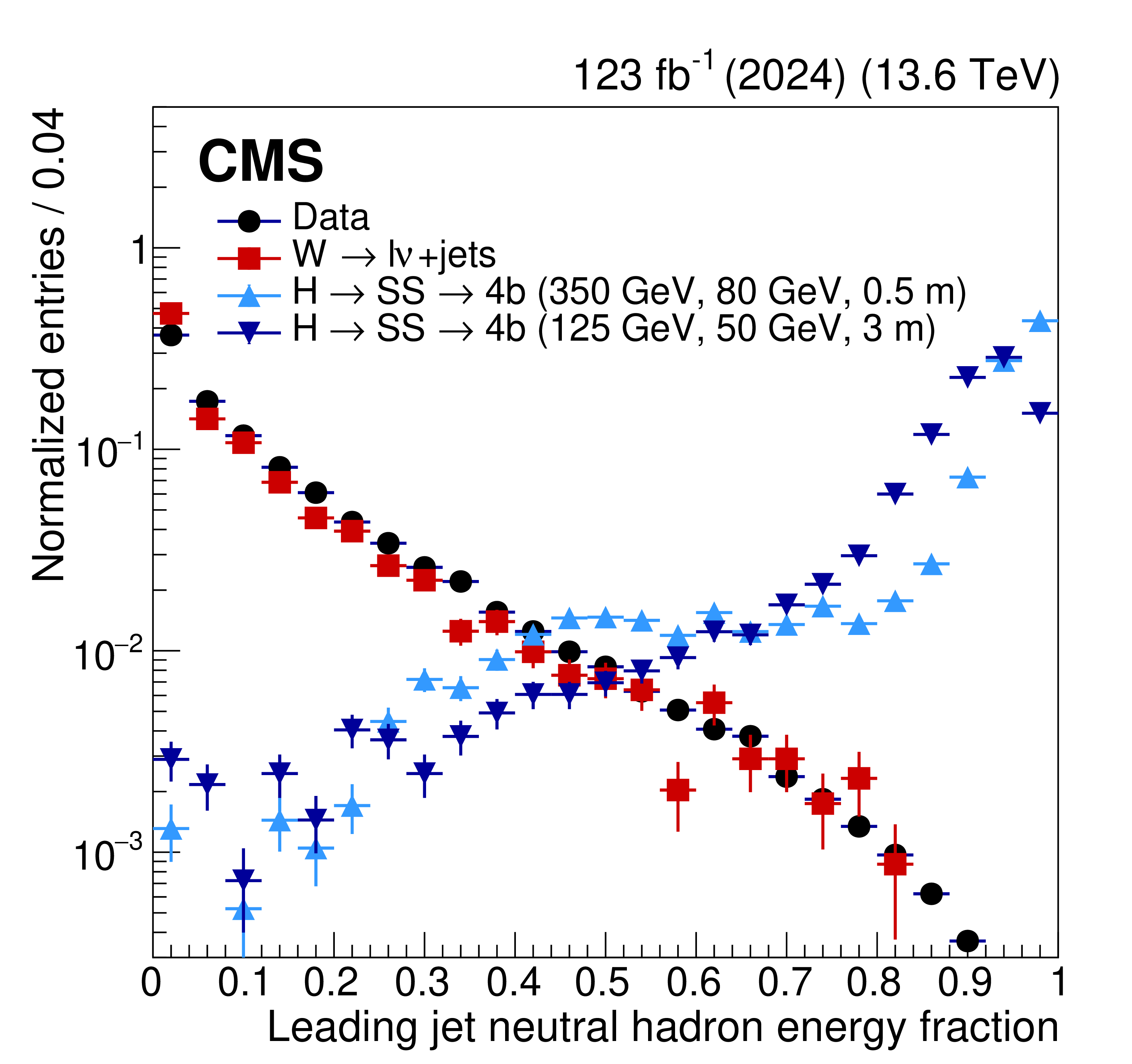

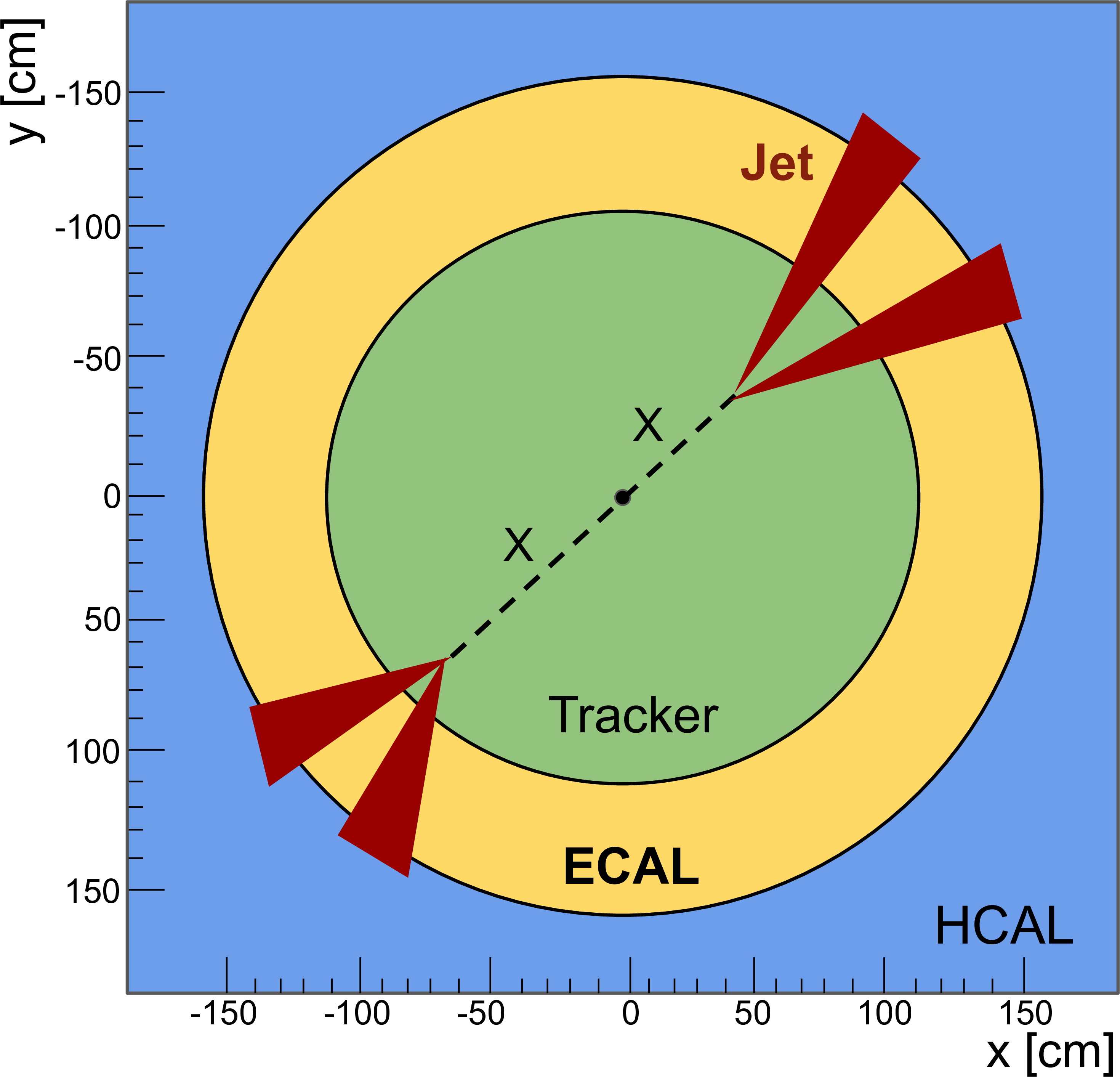

The HLT efficiency of the CalRatio trigger as a function of the leading PF jet NHEF in 2024 data, measured with respect to a logical OR of the HCAL-based LLP L1 jet triggers (left). Distribution of the leading PF jet NHEF (right) in 2024 data (black circles), $ \mathrm{W} \to \ell\nu $ background simulation for 2024 conditions (red squares), and $ \mathrm{H} \to \text{S}\text{S} \to \mathrm{b}\overline{\mathrm{b}}\mathrm{b}\overline{\mathrm{b}} $ signal simulation for 2023 conditions (blue and purple triangles). Events are required to have $ H_{\mathrm{T}} > $ 200 GeV and the leading jet is required to have $ p_{\mathrm{T}} > $ 60 GeV and $ |\eta| < $ 1.5; these requirements are equivalent to the respective HLT jet object selections. The signal distributions additionally require the leading jet to be matched to an LLP decaying anywhere inside the barrel calorimeter volume (129 $ < R < 295 \text{cm} $). The clear separation between the displaced signal and the prompt background in the right plot motivates the development of the CalRatio trigger. |

png pdf |

Figure 25-a:

The HLT efficiency of the CalRatio trigger as a function of the leading PF jet NHEF in 2024 data, measured with respect to a logical OR of the HCAL-based LLP L1 jet triggers (left). Distribution of the leading PF jet NHEF (right) in 2024 data (black circles), $ \mathrm{W} \to \ell\nu $ background simulation for 2024 conditions (red squares), and $ \mathrm{H} \to \text{S}\text{S} \to \mathrm{b}\overline{\mathrm{b}}\mathrm{b}\overline{\mathrm{b}} $ signal simulation for 2023 conditions (blue and purple triangles). Events are required to have $ H_{\mathrm{T}} > $ 200 GeV and the leading jet is required to have $ p_{\mathrm{T}} > $ 60 GeV and $ |\eta| < $ 1.5; these requirements are equivalent to the respective HLT jet object selections. The signal distributions additionally require the leading jet to be matched to an LLP decaying anywhere inside the barrel calorimeter volume (129 $ < R < 295 \text{cm} $). The clear separation between the displaced signal and the prompt background in the right plot motivates the development of the CalRatio trigger. |

png pdf |

Figure 25-b:

The HLT efficiency of the CalRatio trigger as a function of the leading PF jet NHEF in 2024 data, measured with respect to a logical OR of the HCAL-based LLP L1 jet triggers (left). Distribution of the leading PF jet NHEF (right) in 2024 data (black circles), $ \mathrm{W} \to \ell\nu $ background simulation for 2024 conditions (red squares), and $ \mathrm{H} \to \text{S}\text{S} \to \mathrm{b}\overline{\mathrm{b}}\mathrm{b}\overline{\mathrm{b}} $ signal simulation for 2023 conditions (blue and purple triangles). Events are required to have $ H_{\mathrm{T}} > $ 200 GeV and the leading jet is required to have $ p_{\mathrm{T}} > $ 60 GeV and $ |\eta| < $ 1.5; these requirements are equivalent to the respective HLT jet object selections. The signal distributions additionally require the leading jet to be matched to an LLP decaying anywhere inside the barrel calorimeter volume (129 $ < R < 295 \text{cm} $). The clear separation between the displaced signal and the prompt background in the right plot motivates the development of the CalRatio trigger. |

png pdf |

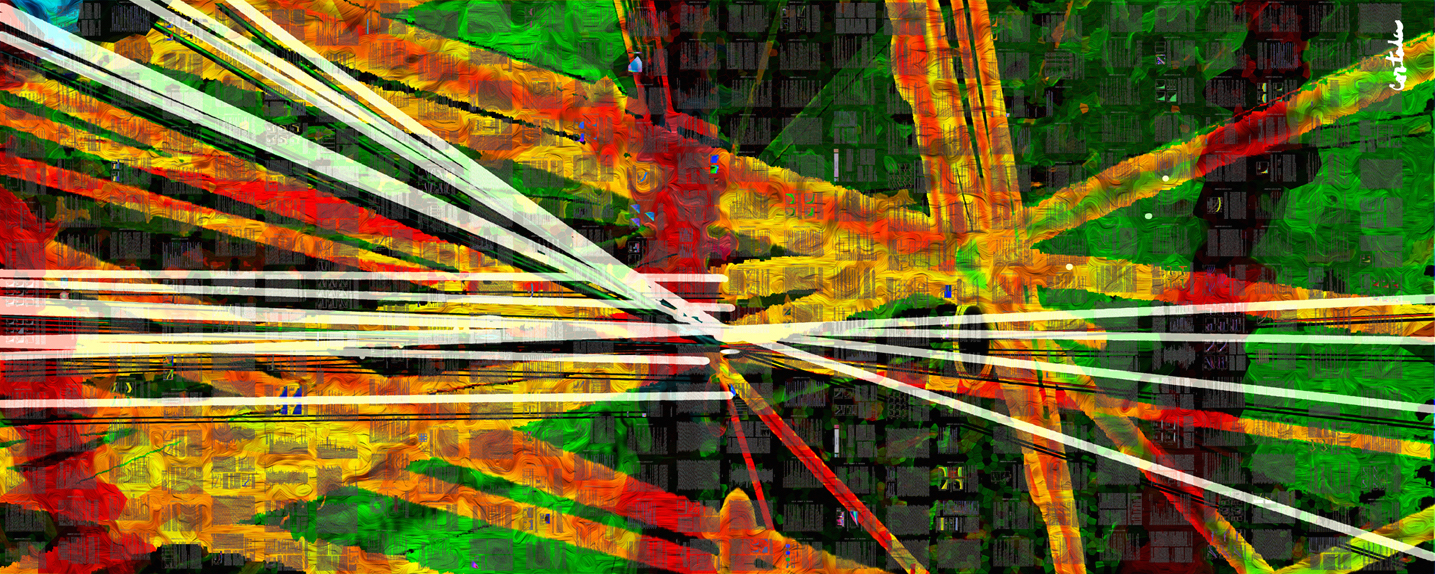

Figure 26:

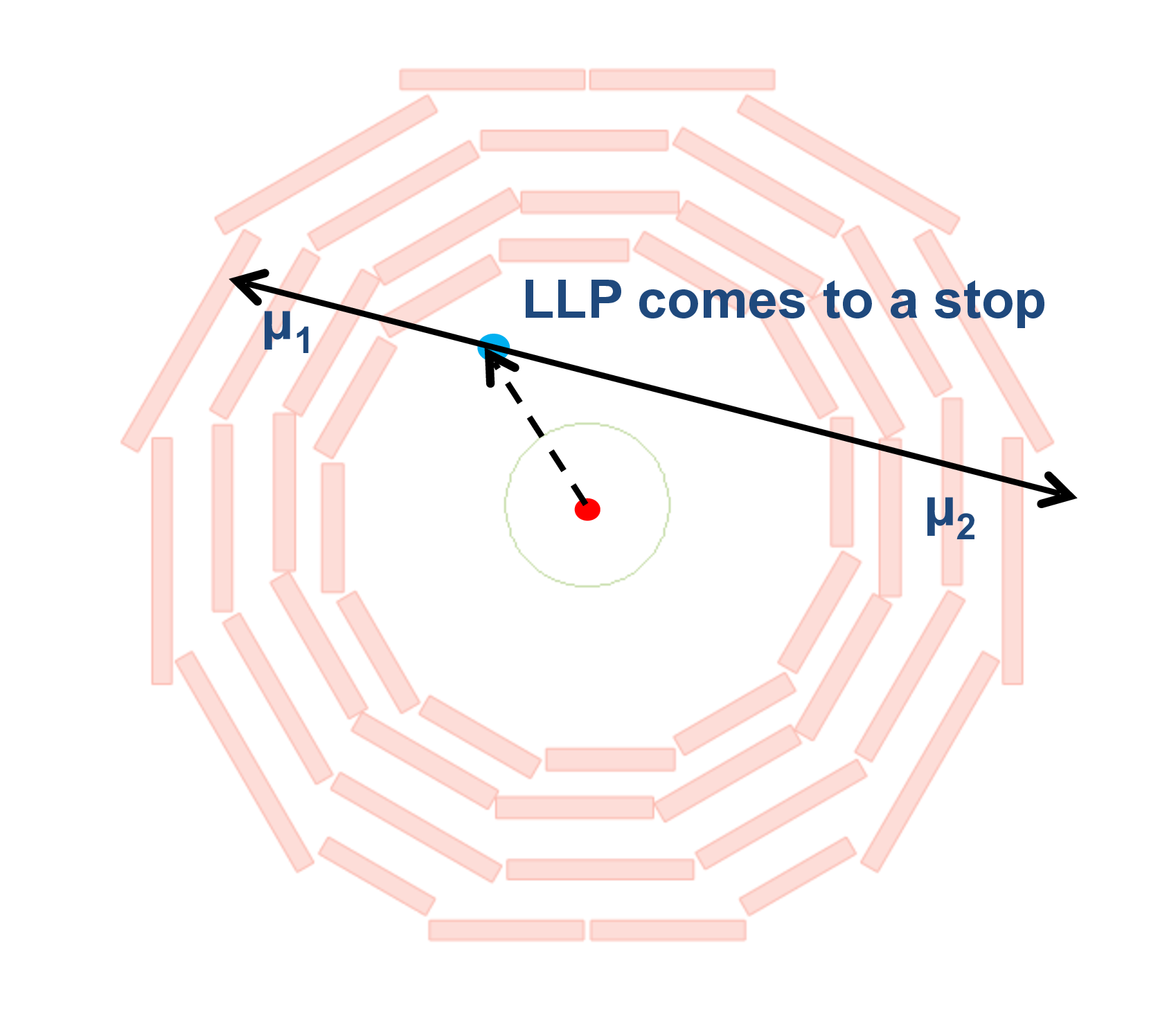

Diagram of a typical delayed-jet signal event. |

png pdf |

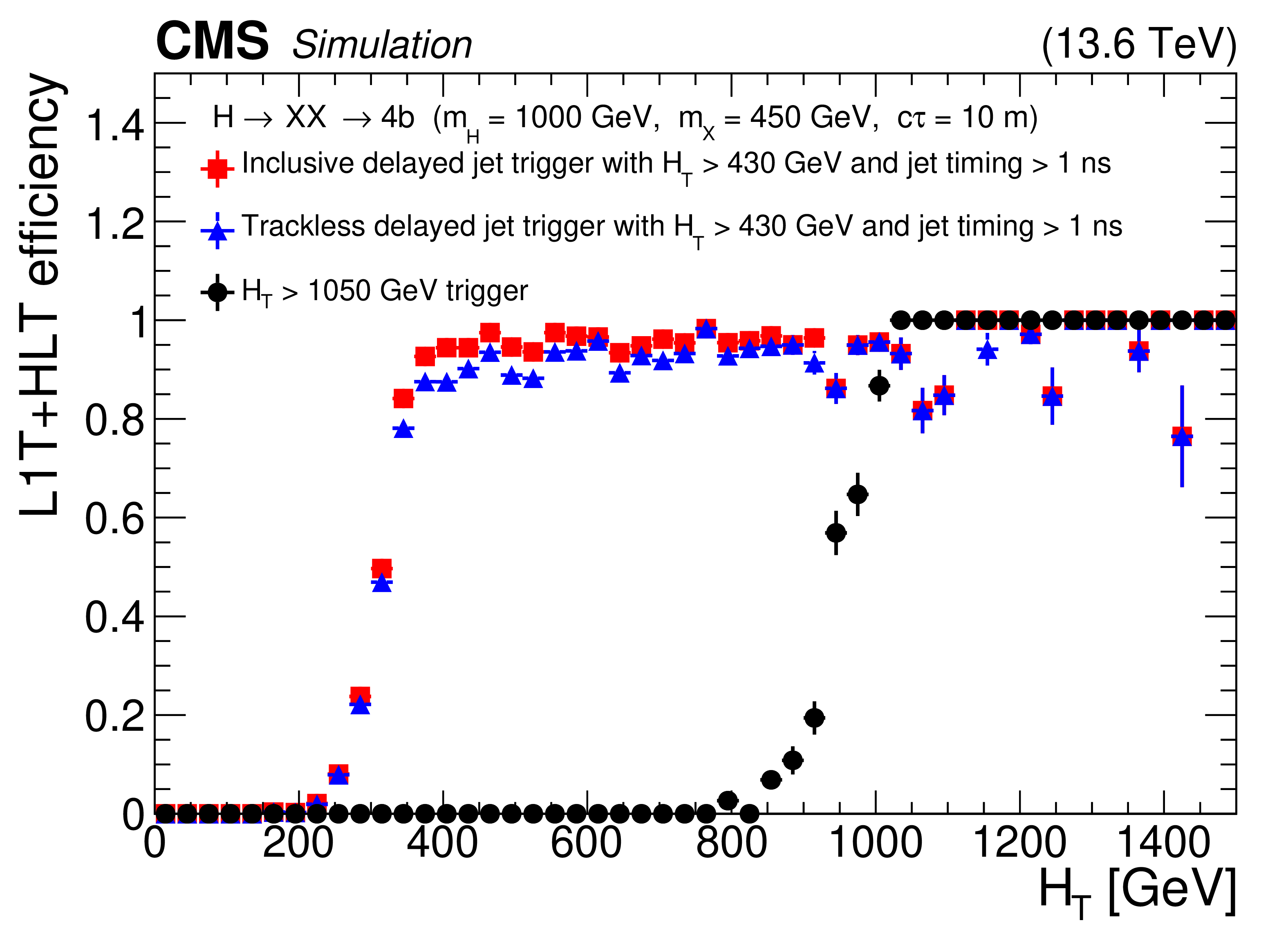

Figure 27:

The L1T+HLT efficiency of the inclusive and trackless delayed-jet triggers introduced in Run 3 in red squares (blue triangles), for 2022 conditions, and the $ H_{\mathrm{T}} $ trigger (black circles), which was the most appropriate path available in Run 2, for a $ \mathrm{H} \to \mathrm{X}\mathrm{X} \to 4\mathrm{b} $ signal with $ m_{\mathrm{H}}= $ 1000 GeV, $ m_{\mathrm{X}}= $ 450 GeV, and $ c\tau= $ 10 m. The addition of these delayed-jet triggers results in a significant improvement in the efficiency of the signal for 430 $ < H_{\mathrm{T}} < $ 1050 GeV. These plots include events with jets with $ p_{\mathrm{T}} > $ 40 GeV, number of ECAL cells $ > $ 5, barrel region with $ |\eta| < $ 1.48, and jet timing $ > $ 1 ns. |

png pdf |

Figure 28:

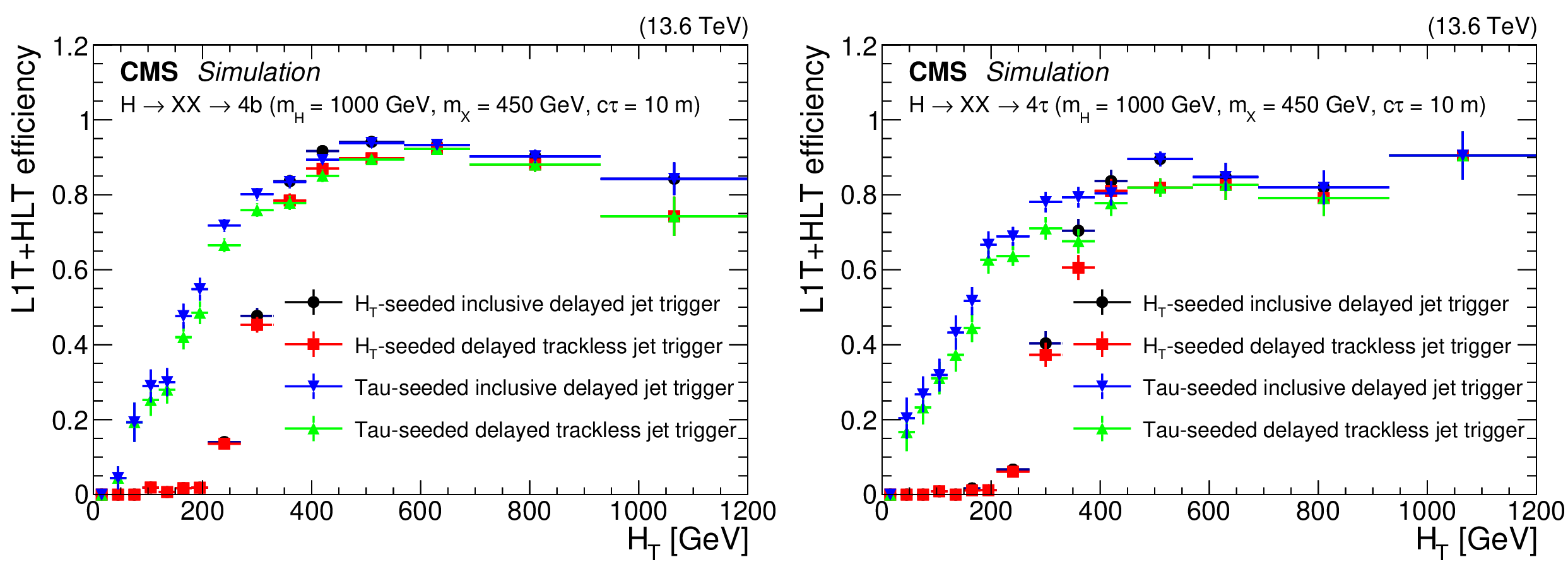

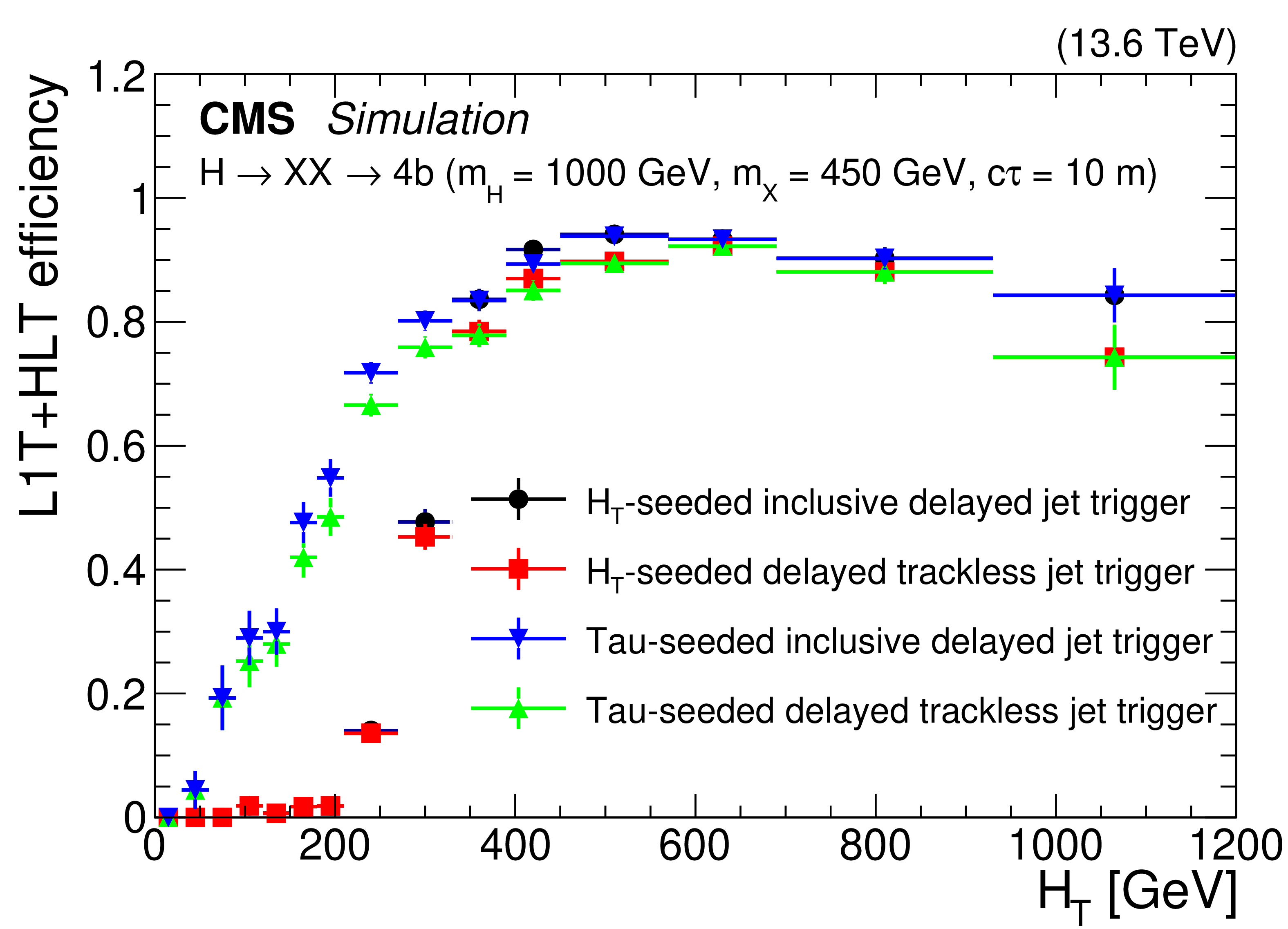

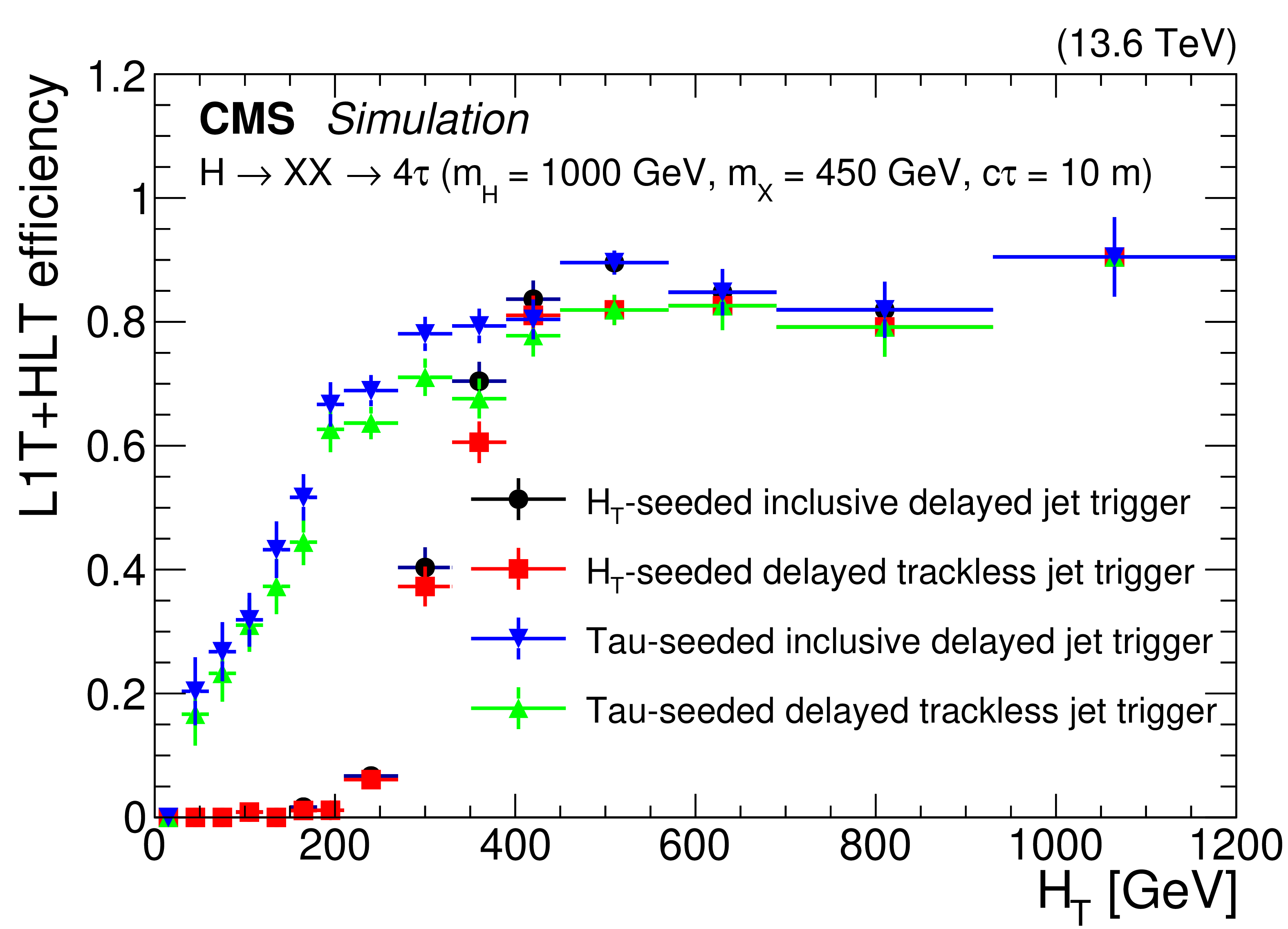

The L1T+HLT efficiency of the delayed-jet triggers for signal models with $ \mathrm{H} \to \mathrm{X}\mathrm{X} \to 4\mathrm{b} $ (left) and $ \mathrm{H} \to \mathrm{X}\mathrm{X} \to 4\tau $ (right), with $ m_{\mathrm{H}}= $ 1000 GeV, $ m_{\mathrm{X}}= $ 450 GeV and $ c\tau= $ 10 m, for 2022 conditions. The improvement from the tau triggers (blue and green triangles) is evident in the $ H_{\mathrm{T}} < $ 430 GeV region compared to the $ H_{\mathrm{T}} $-seeded triggers (black circles and red squares). These plots include events with jets with $ p_{\mathrm{T}} > $ 40 GeV, number of ECAL cells $ > $ 5, barrel region with $ |\eta| < $ 1.48, and jet timing $ > $ 2 ns. |

png pdf |

Figure 28-a:

The L1T+HLT efficiency of the delayed-jet triggers for signal models with $ \mathrm{H} \to \mathrm{X}\mathrm{X} \to 4\mathrm{b} $ (left) and $ \mathrm{H} \to \mathrm{X}\mathrm{X} \to 4\tau $ (right), with $ m_{\mathrm{H}}= $ 1000 GeV, $ m_{\mathrm{X}}= $ 450 GeV and $ c\tau= $ 10 m, for 2022 conditions. The improvement from the tau triggers (blue and green triangles) is evident in the $ H_{\mathrm{T}} < $ 430 GeV region compared to the $ H_{\mathrm{T}} $-seeded triggers (black circles and red squares). These plots include events with jets with $ p_{\mathrm{T}} > $ 40 GeV, number of ECAL cells $ > $ 5, barrel region with $ |\eta| < $ 1.48, and jet timing $ > $ 2 ns. |

png pdf |

Figure 28-b:

The L1T+HLT efficiency of the delayed-jet triggers for signal models with $ \mathrm{H} \to \mathrm{X}\mathrm{X} \to 4\mathrm{b} $ (left) and $ \mathrm{H} \to \mathrm{X}\mathrm{X} \to 4\tau $ (right), with $ m_{\mathrm{H}}= $ 1000 GeV, $ m_{\mathrm{X}}= $ 450 GeV and $ c\tau= $ 10 m, for 2022 conditions. The improvement from the tau triggers (blue and green triangles) is evident in the $ H_{\mathrm{T}} < $ 430 GeV region compared to the $ H_{\mathrm{T}} $-seeded triggers (black circles and red squares). These plots include events with jets with $ p_{\mathrm{T}} > $ 40 GeV, number of ECAL cells $ > $ 5, barrel region with $ |\eta| < $ 1.48, and jet timing $ > $ 2 ns. |

png pdf |

Figure 29:

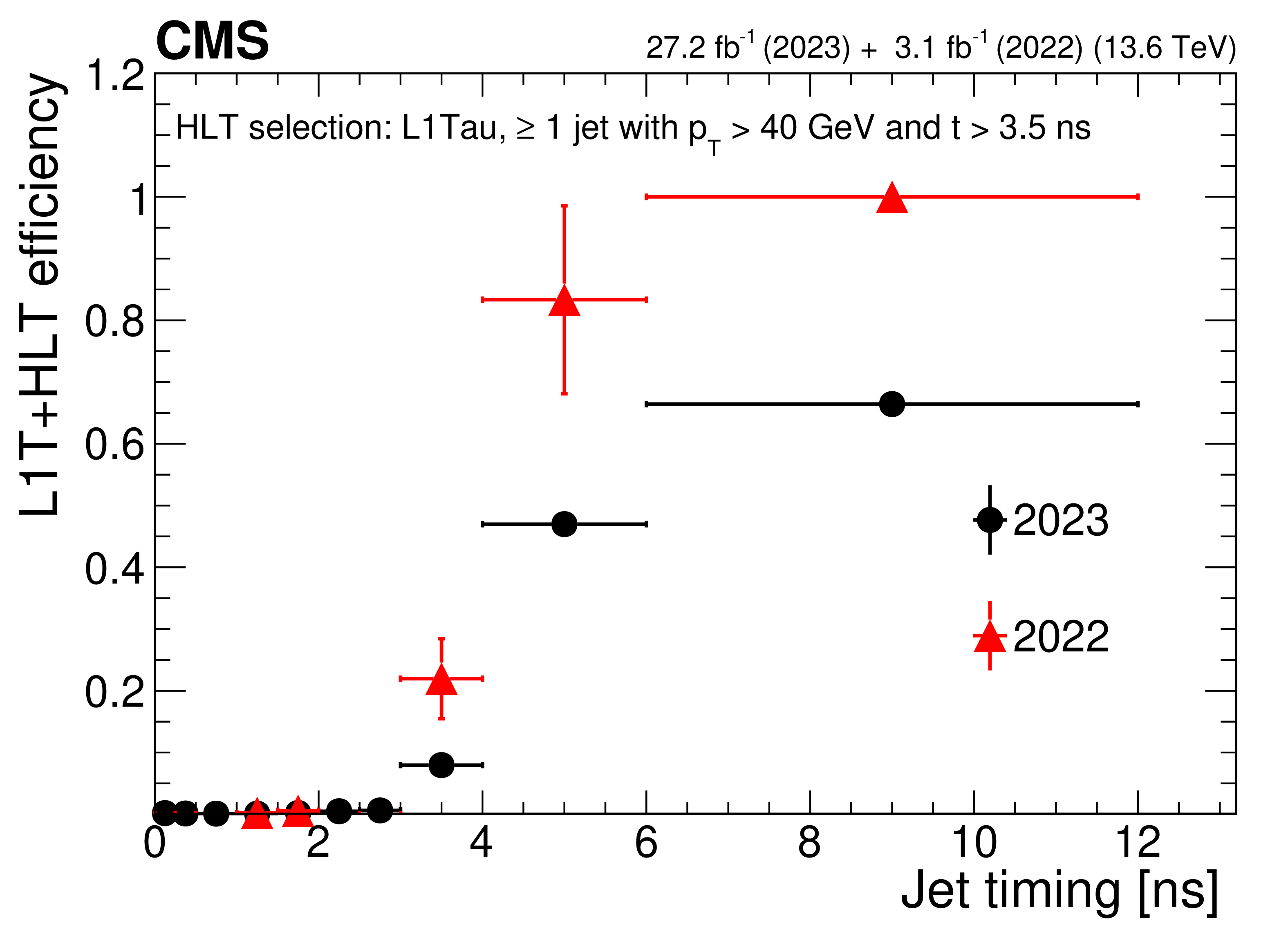

The L1T+HLT efficiency of the delayed-jet triggers as a function of jet timing for 2022 (red triangles) and 2023 (black circles) data-taking periods for the $ H_{\mathrm{T}} $-seeded trigger (left) and the $ \tau $-seeded trigger (right). A clear rise in efficiency is evident around the threshold values. The plots include events that pass the $ p_{\mathrm{T}}^\text{miss} > $ 200 GeV trigger and have at least one barrel jet with $ p_{\mathrm{T}} > $ 50 GeV, number of ECAL cells $ > $ 8, and ECAL energy $ > $ 25 GeV. The $ H_{\mathrm{T}} $ is calculated using the scalar sum of jets with offline $ p_{\mathrm{T}} > $ 40 GeV, and this is different from the $ H_{\mathrm{T}} $ calculation used at the HLT level, contributing to the trigger inefficiencies. The maximum jet time accepted by the trigger is 12.5\unitns. |

png pdf |

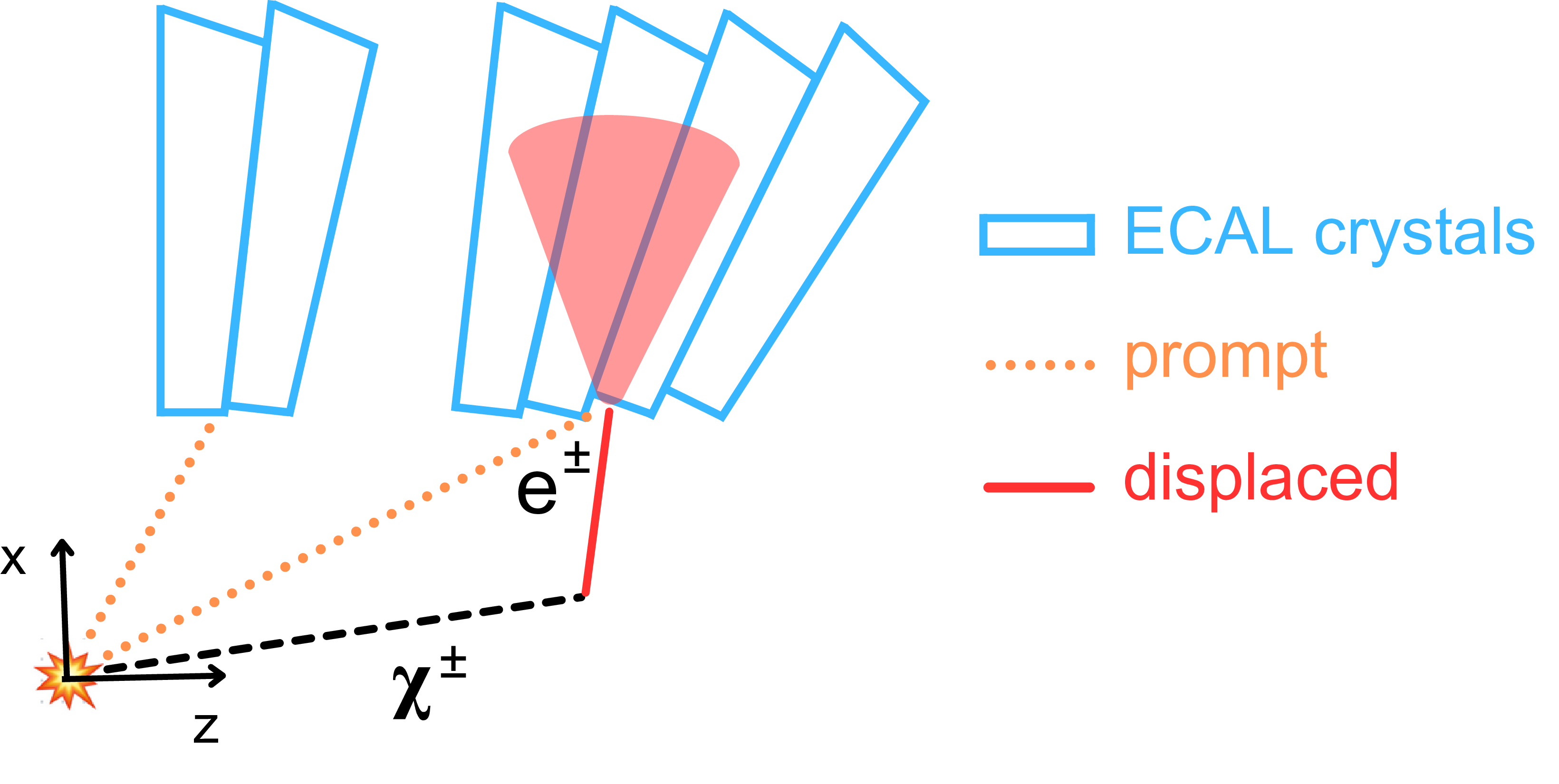

Figure 30:

Diagram of a prompt (orange dotted line) and displaced (red solid line) electron, which comes from the decay of a chargino, reaching the ECAL in the $ x-z $ plane. The time measurement is shifted so that all prompt electron signals register the same time, no matter where they are located in the ECAL. An electron produced at a displaced vertex thus arrives delayed compared to a prompt particle. |

png pdf |

Figure 31:

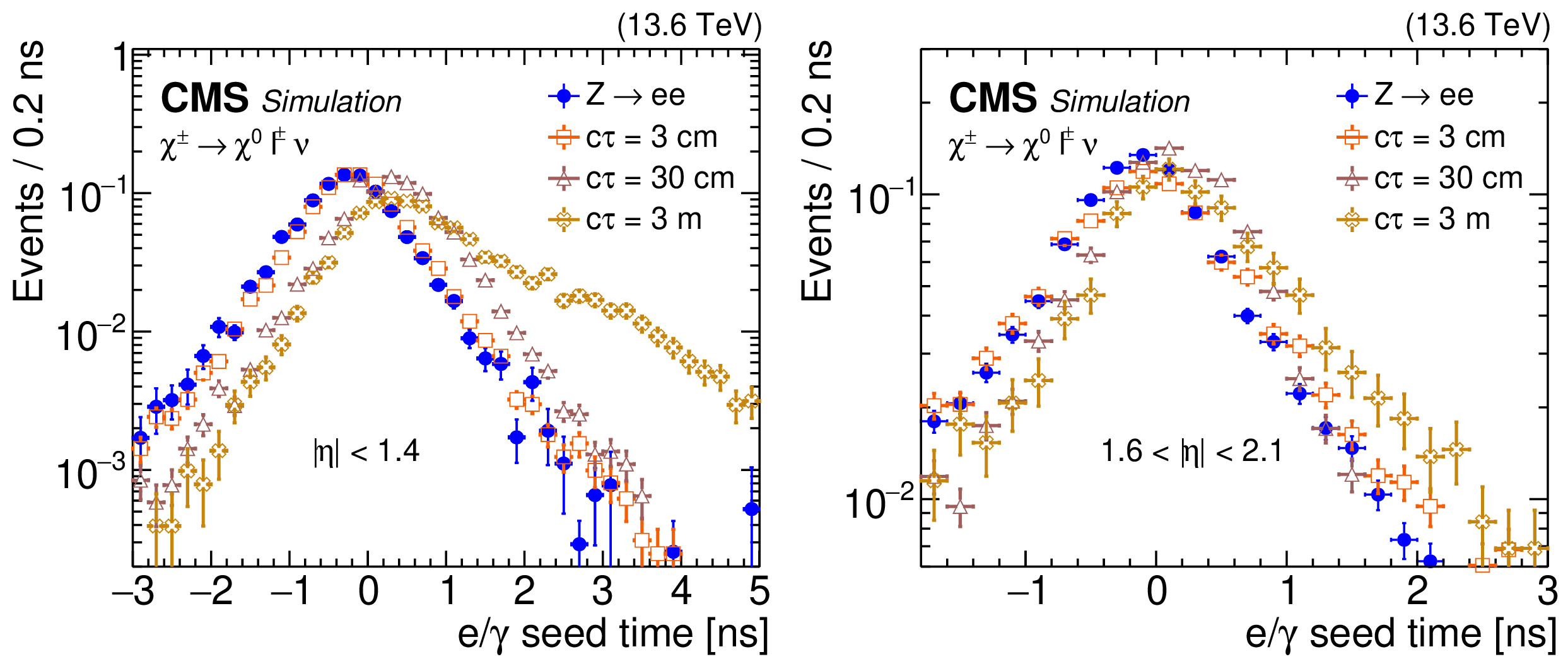

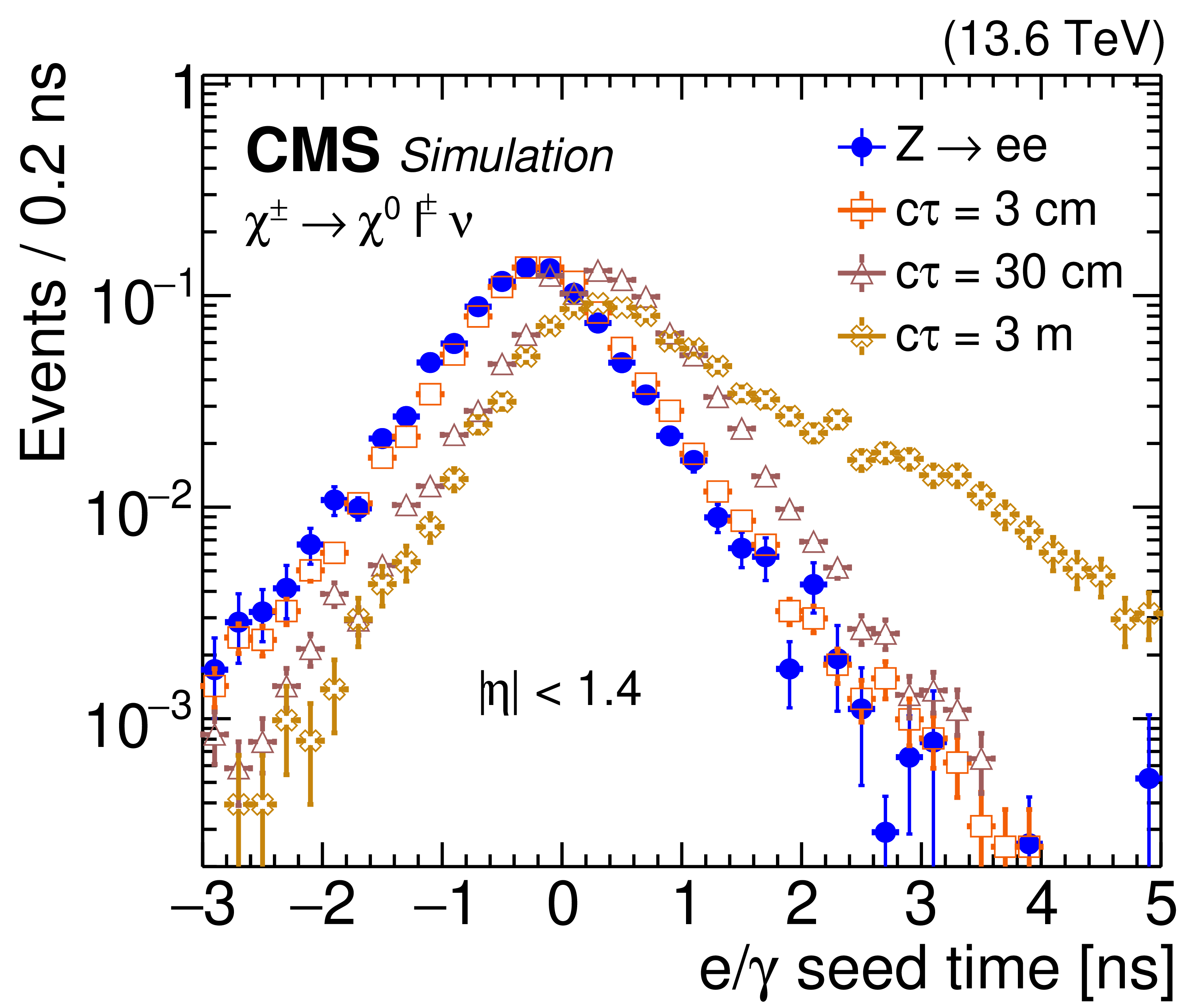

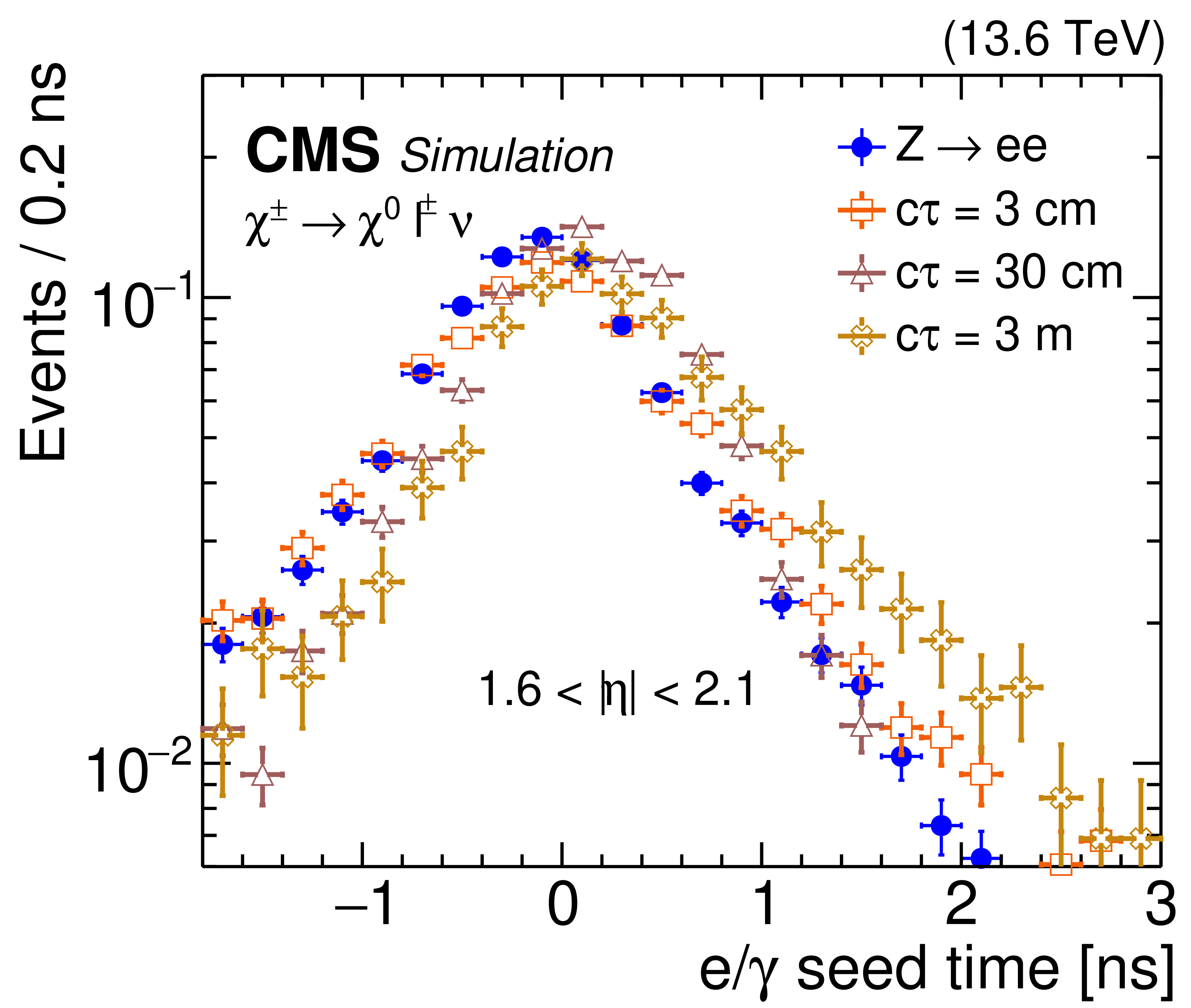

The ECAL time delay of the $ \mathrm{e}/\gamma $ L1 seeds in the barrel (left) and endcap (right). The distributions are shown for $ \mathrm{Z} \to \mathrm{e}\mathrm{e} $ simulation (filled blue circles) and $ \chi^{0} c\tau $ values of 3$ \text{cm} $ (open red squares), 30$ \text{cm} $ (open purple triangles) and 3\unitm (open yellow crosses), assuming the singlet-triplet Higgs dark portal model ($ \chi^{\pm} \to \chi^{0} \ell \nu $, where the $ \chi^{\pm} $ has a mass of 220 GeV and the $ \chi^{0} $ has a mass of 200 GeV), for 2023 conditions. The distributions are normalized to unity. |

png pdf |

Figure 31-a:

The ECAL time delay of the $ \mathrm{e}/\gamma $ L1 seeds in the barrel (left) and endcap (right). The distributions are shown for $ \mathrm{Z} \to \mathrm{e}\mathrm{e} $ simulation (filled blue circles) and $ \chi^{0} c\tau $ values of 3$ \text{cm} $ (open red squares), 30$ \text{cm} $ (open purple triangles) and 3\unitm (open yellow crosses), assuming the singlet-triplet Higgs dark portal model ($ \chi^{\pm} \to \chi^{0} \ell \nu $, where the $ \chi^{\pm} $ has a mass of 220 GeV and the $ \chi^{0} $ has a mass of 200 GeV), for 2023 conditions. The distributions are normalized to unity. |

png pdf |

Figure 31-b:

The ECAL time delay of the $ \mathrm{e}/\gamma $ L1 seeds in the barrel (left) and endcap (right). The distributions are shown for $ \mathrm{Z} \to \mathrm{e}\mathrm{e} $ simulation (filled blue circles) and $ \chi^{0} c\tau $ values of 3$ \text{cm} $ (open red squares), 30$ \text{cm} $ (open purple triangles) and 3\unitm (open yellow crosses), assuming the singlet-triplet Higgs dark portal model ($ \chi^{\pm} \to \chi^{0} \ell \nu $, where the $ \chi^{\pm} $ has a mass of 220 GeV and the $ \chi^{0} $ has a mass of 200 GeV), for 2023 conditions. The distributions are normalized to unity. |

png pdf |

Figure 32:

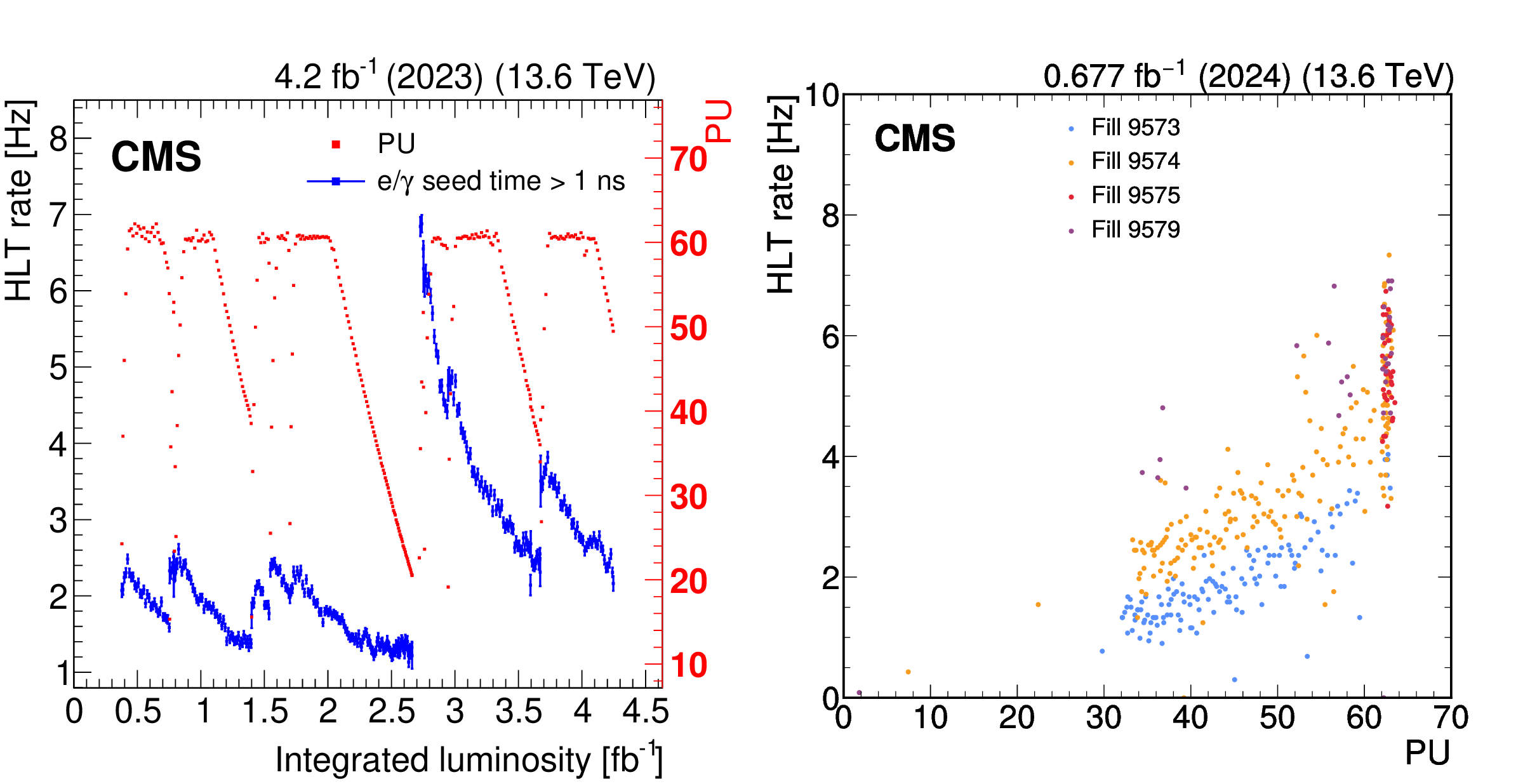

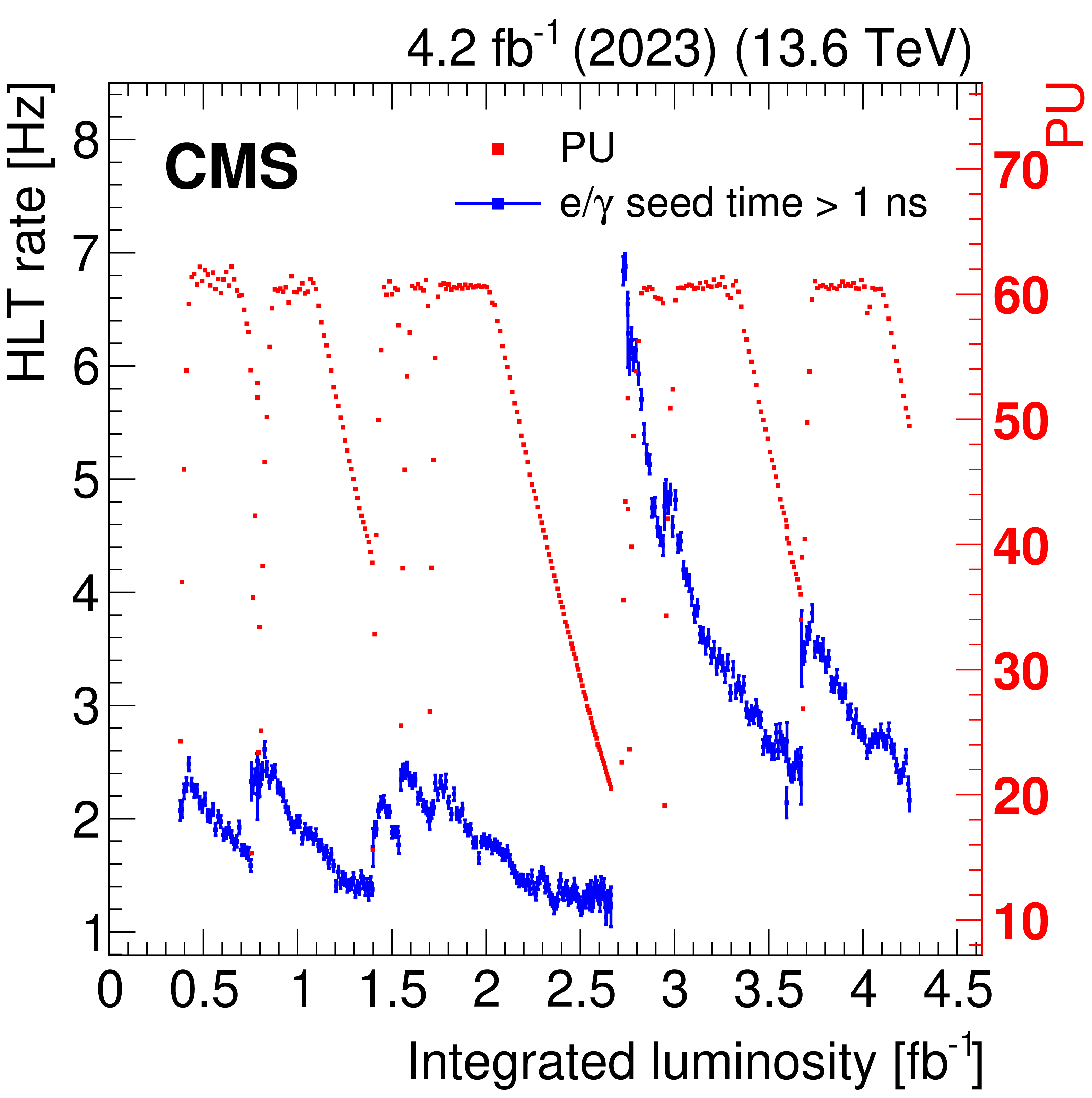

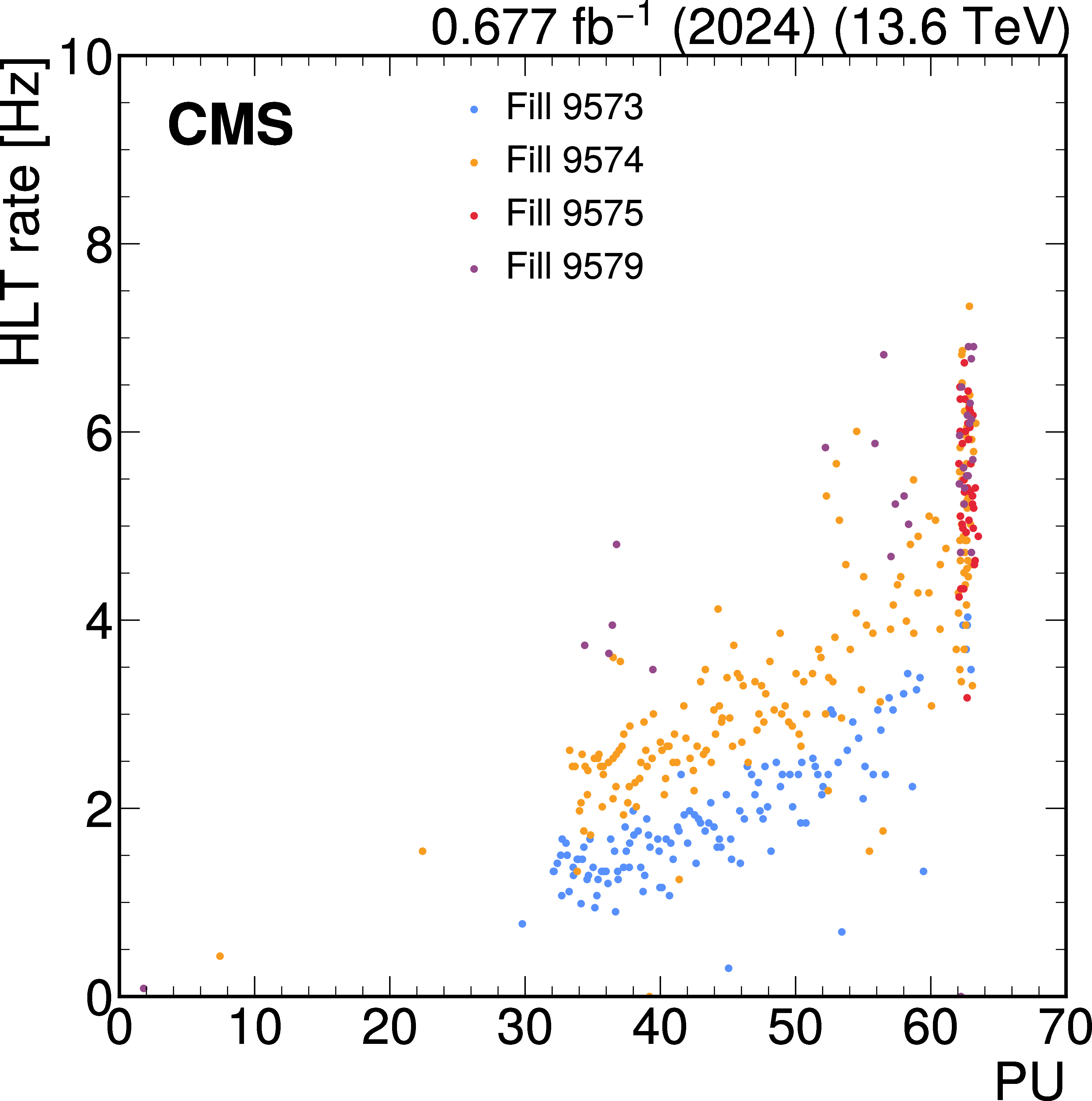

The HLT rate (blue points) of the delayed-diphoton trigger for a few representative runs in the first data collected in 2023, corresponding to an integrated luminosity of 4.2 fb$ ^{-1} $, compared with the PU during the same data-taking period (red points), as a function of integrated luminosity (left). The rate decreases nonlinearly during a single fill as a result of the increasing crystal opacity. It recovers by the start of the next fill with $ {<}1% $ reduction in rate between the fills. The rate generally increased throughout the year because of periodic online calibrations to mitigate the loss in trigger efficiency, which is a result of the ECAL crystal radiation damage. The delayed-diphoton trigger rate is shown as a function of PU for selected fills in 2024 data, at an instantaneous luminosity of approximately \instL1.8 (right). The trigger rate displays a linear dependency on PU. |

png pdf |

Figure 32-a:

The HLT rate (blue points) of the delayed-diphoton trigger for a few representative runs in the first data collected in 2023, corresponding to an integrated luminosity of 4.2 fb$ ^{-1} $, compared with the PU during the same data-taking period (red points), as a function of integrated luminosity (left). The rate decreases nonlinearly during a single fill as a result of the increasing crystal opacity. It recovers by the start of the next fill with $ {<}1% $ reduction in rate between the fills. The rate generally increased throughout the year because of periodic online calibrations to mitigate the loss in trigger efficiency, which is a result of the ECAL crystal radiation damage. The delayed-diphoton trigger rate is shown as a function of PU for selected fills in 2024 data, at an instantaneous luminosity of approximately \instL1.8 (right). The trigger rate displays a linear dependency on PU. |

png pdf |

Figure 32-b:

The HLT rate (blue points) of the delayed-diphoton trigger for a few representative runs in the first data collected in 2023, corresponding to an integrated luminosity of 4.2 fb$ ^{-1} $, compared with the PU during the same data-taking period (red points), as a function of integrated luminosity (left). The rate decreases nonlinearly during a single fill as a result of the increasing crystal opacity. It recovers by the start of the next fill with $ {<}1% $ reduction in rate between the fills. The rate generally increased throughout the year because of periodic online calibrations to mitigate the loss in trigger efficiency, which is a result of the ECAL crystal radiation damage. The delayed-diphoton trigger rate is shown as a function of PU for selected fills in 2024 data, at an instantaneous luminosity of approximately \instL1.8 (right). The trigger rate displays a linear dependency on PU. |

png pdf |

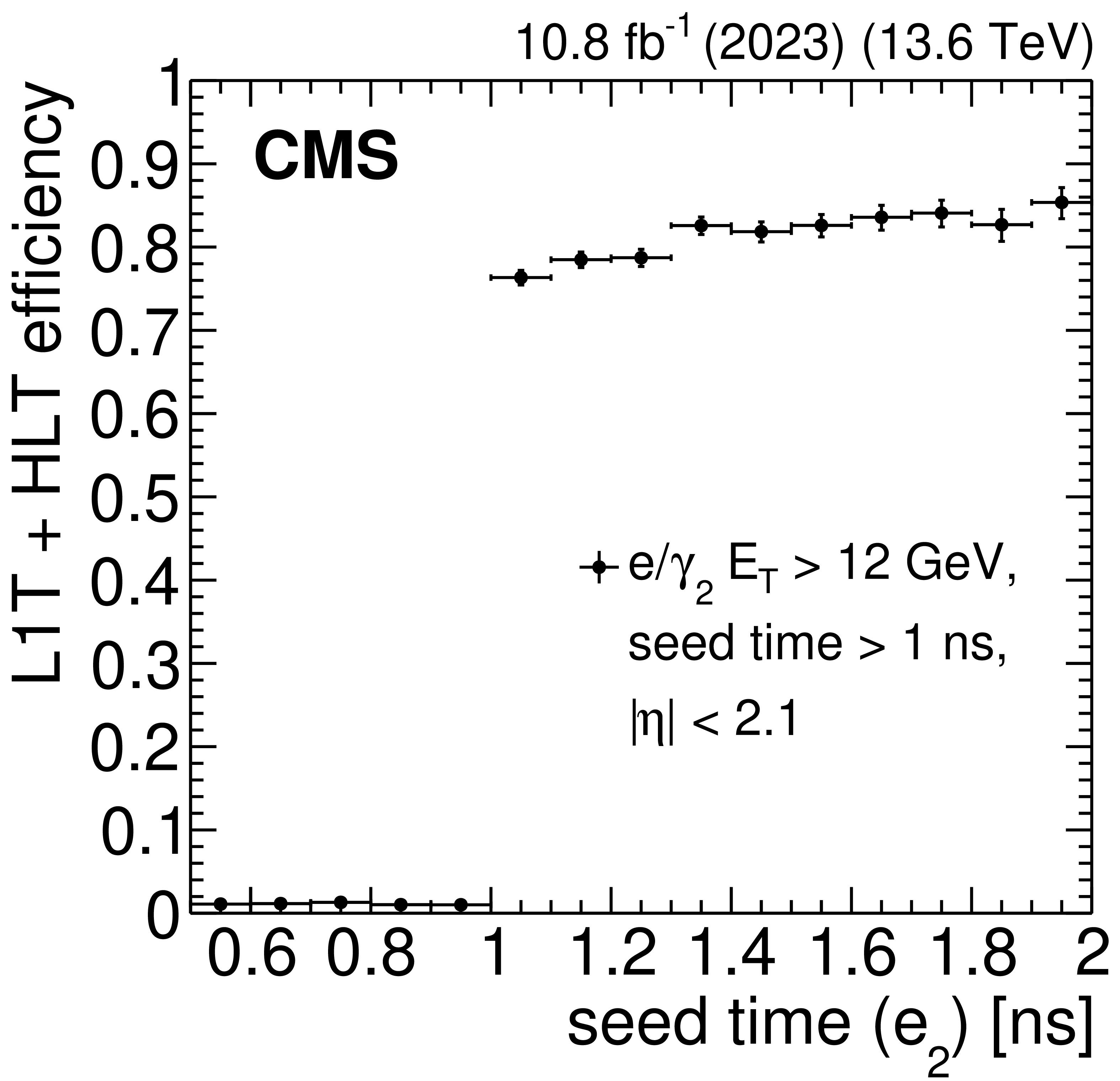

Figure 33:

The L1T+HLT efficiency of the delayed-diphoton trigger as a function of the subleading probe electron ($ \mathrm{e}_2 $) supercluster seed time, measured with data collected in 2023. At the HLT, the subleading $ \mathrm{e}/\gamma $ supercluster ($ \mathrm{e}/\gamma_2 $) is required to have $ E_{\mathrm{T}} > $ 12 GeV, $ |\eta| < $ 2.1, and a seed time $ {>} $ 1 ns. The trigger reaches maximum efficiency above 1\unitns. |

png pdf |

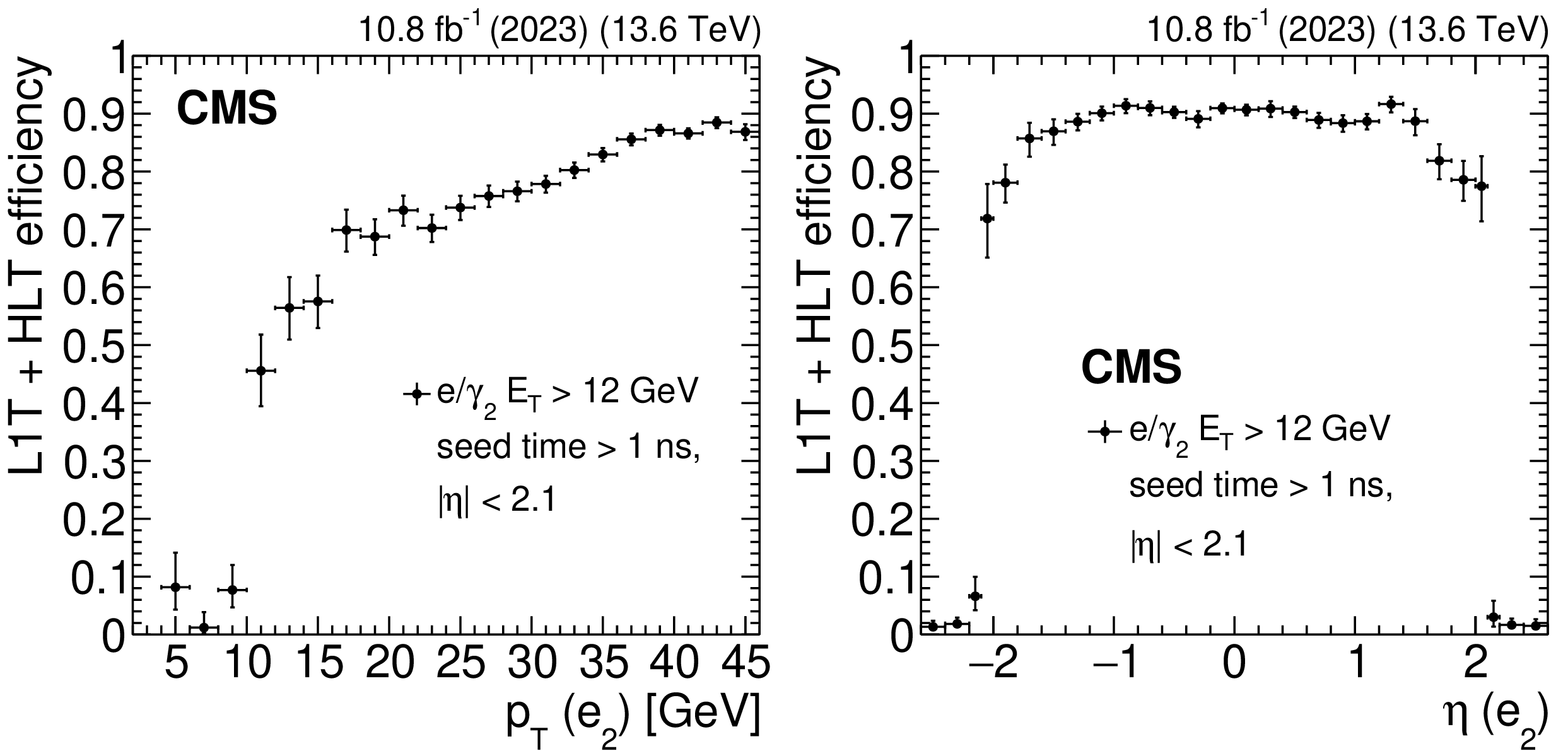

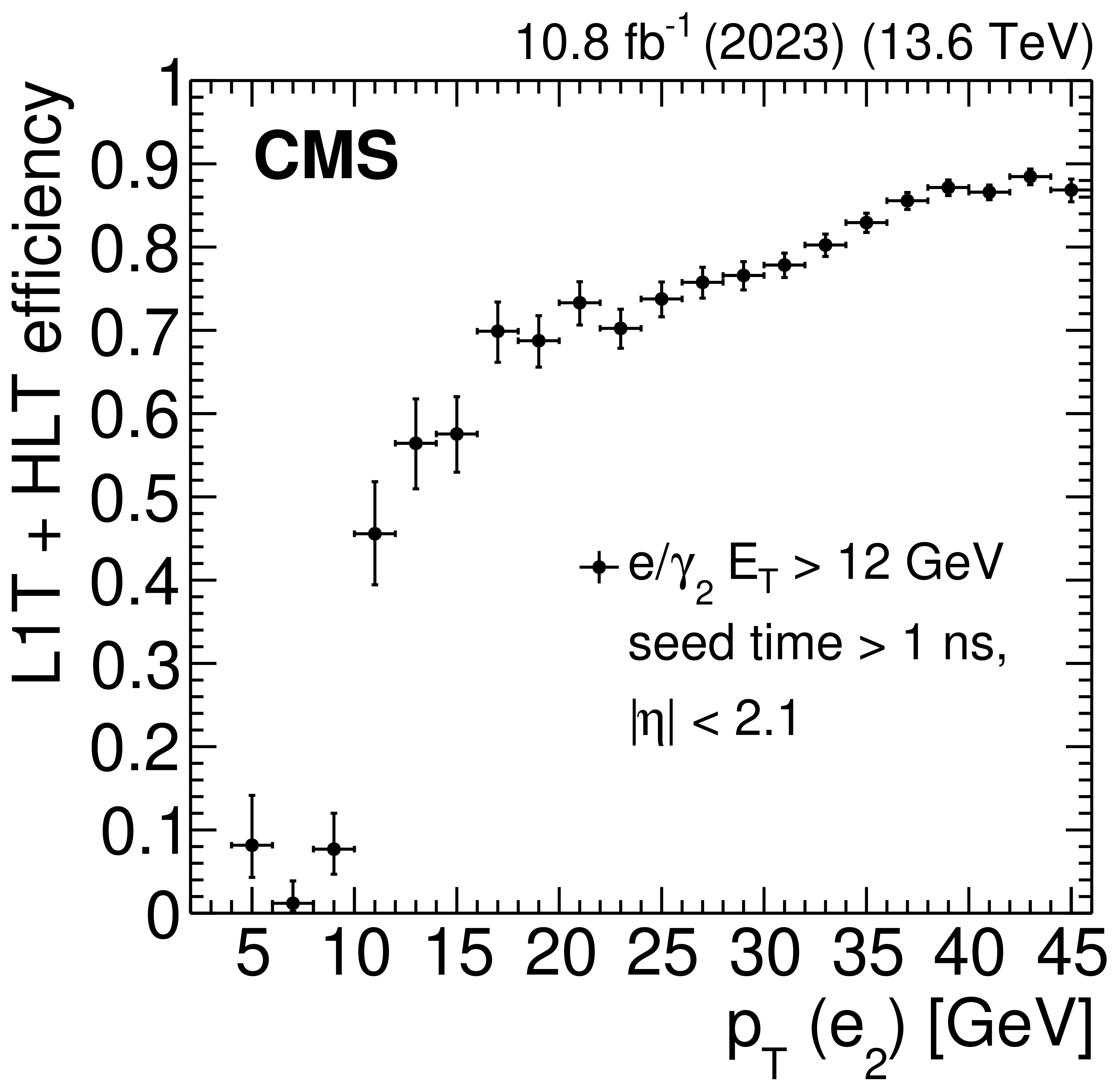

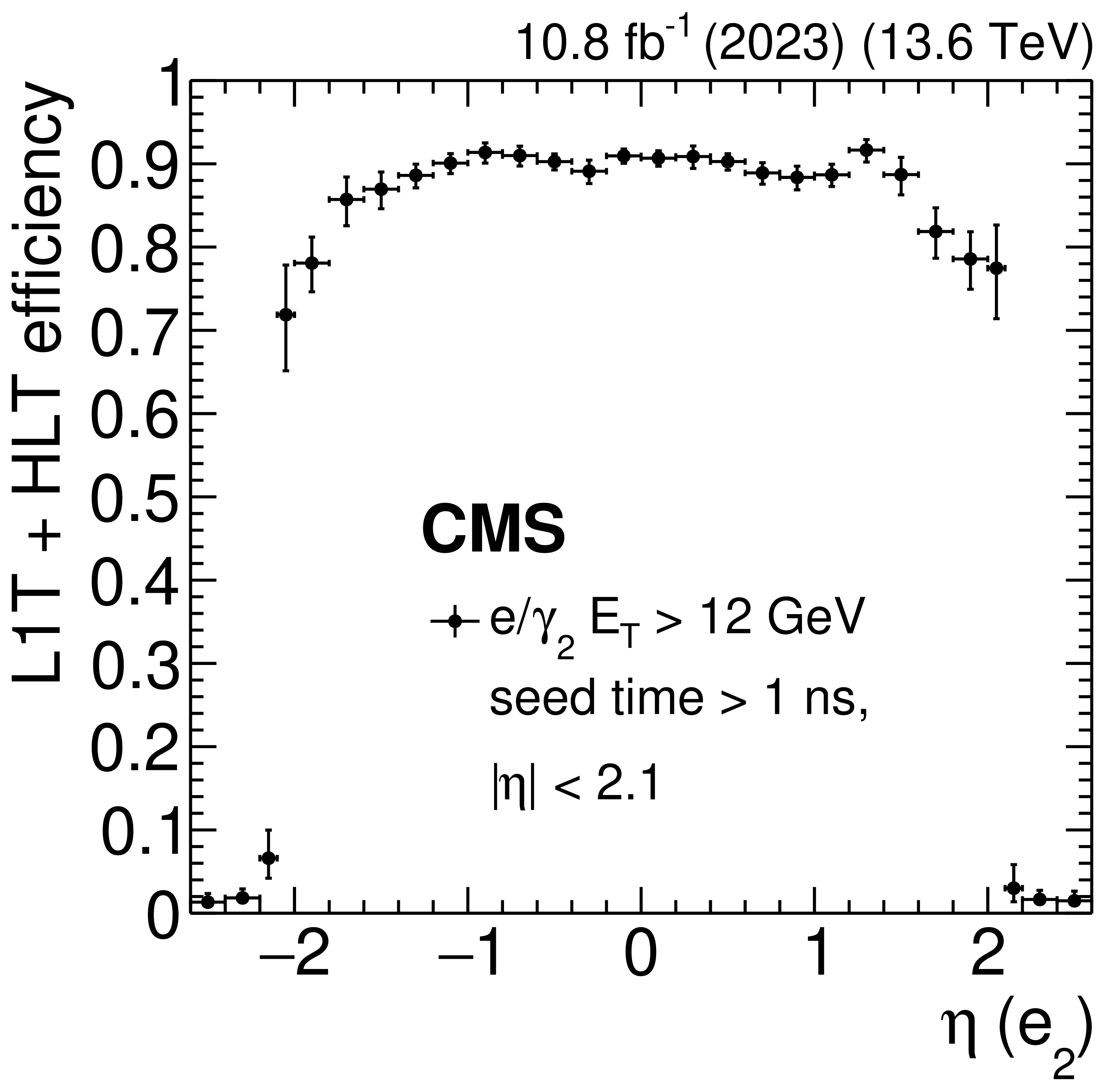

Figure 34:

The L1T+HLT efficiency of the delayed-diphoton trigger as a function of subleading probe electron ($ \mathrm{e}_2 $) $ p_{\mathrm{T}} $ (left) and $ \eta $ (right), measured with data collected in 2023. At the HLT, the subleading $ \mathrm{e}/\gamma $ supercluster ($ \mathrm{e}/\gamma_2 $) is required to have $ E_{\mathrm{T}} > $ 12 GeV, $ |\eta| < $ 2.1, and a seed time $ {>} $ 1 ns. The efficiency rises sharply for $ p_{\mathrm{T}} > $ 12 GeV and plateaus for $ p_{\mathrm{T}} > $ 35 GeV. The slow rise in between is from additional L1 $ H_{\mathrm{T}} $ requirements. The trigger is efficient in the region $ |\eta| < $ 2.1. |

png pdf |

Figure 34-a:

The L1T+HLT efficiency of the delayed-diphoton trigger as a function of subleading probe electron ($ \mathrm{e}_2 $) $ p_{\mathrm{T}} $ (left) and $ \eta $ (right), measured with data collected in 2023. At the HLT, the subleading $ \mathrm{e}/\gamma $ supercluster ($ \mathrm{e}/\gamma_2 $) is required to have $ E_{\mathrm{T}} > $ 12 GeV, $ |\eta| < $ 2.1, and a seed time $ {>} $ 1 ns. The efficiency rises sharply for $ p_{\mathrm{T}} > $ 12 GeV and plateaus for $ p_{\mathrm{T}} > $ 35 GeV. The slow rise in between is from additional L1 $ H_{\mathrm{T}} $ requirements. The trigger is efficient in the region $ |\eta| < $ 2.1. |

png pdf |

Figure 34-b:

The L1T+HLT efficiency of the delayed-diphoton trigger as a function of subleading probe electron ($ \mathrm{e}_2 $) $ p_{\mathrm{T}} $ (left) and $ \eta $ (right), measured with data collected in 2023. At the HLT, the subleading $ \mathrm{e}/\gamma $ supercluster ($ \mathrm{e}/\gamma_2 $) is required to have $ E_{\mathrm{T}} > $ 12 GeV, $ |\eta| < $ 2.1, and a seed time $ {>} $ 1 ns. The efficiency rises sharply for $ p_{\mathrm{T}} > $ 12 GeV and plateaus for $ p_{\mathrm{T}} > $ 35 GeV. The slow rise in between is from additional L1 $ H_{\mathrm{T}} $ requirements. The trigger is efficient in the region $ |\eta| < $ 2.1. |

png pdf |

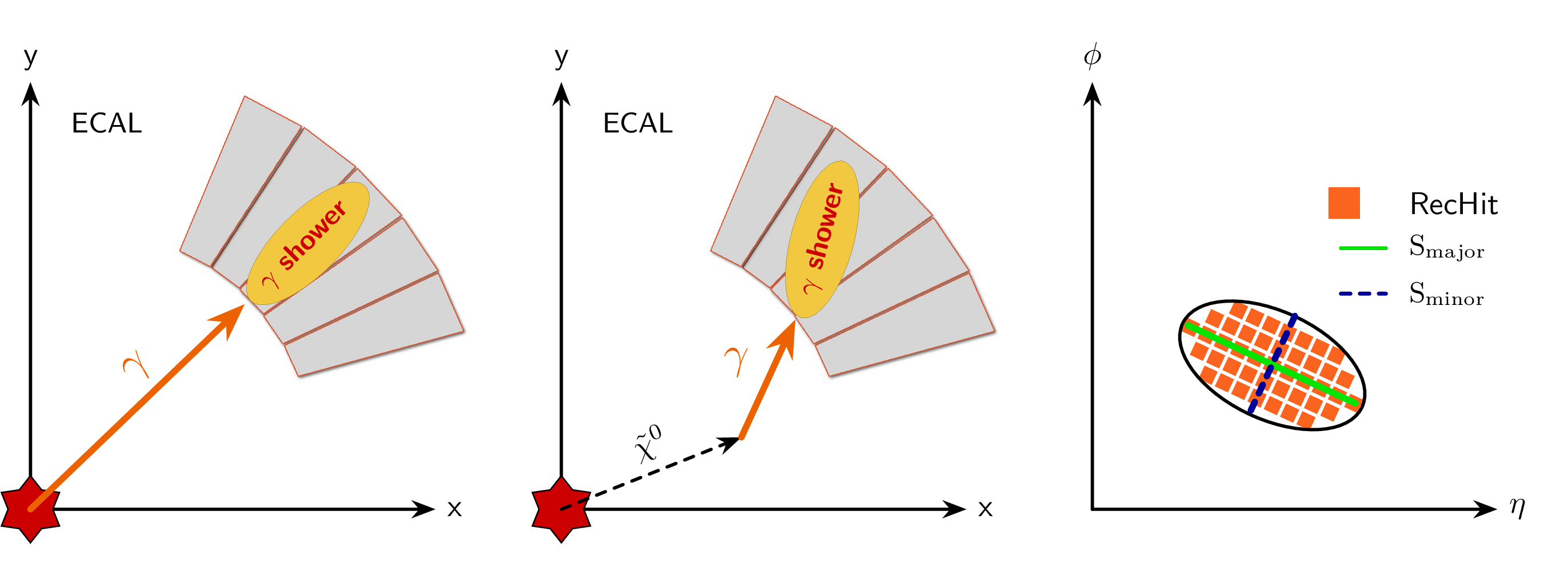

Figure 35:

Diagrams of a promptly decaying photon in the $ x-y $ plane showering in the ECAL (left), a delayed photon produced from a long-lived neutralino $ \tilde{\chi}^{0} $ in the $ x-y $ plane showering later in the ECAL (middle), and an elliptical shower in the $ \eta-\phi $ plane produced from a delayed photon (right). The lengths of the major ($ S_{\text{major}} $) and minor ($ S_{\text{minor}} $) axes of the shower and the reconstructed hits (RecHits) that compose the shower are labeled. |

png pdf |

Figure 36:

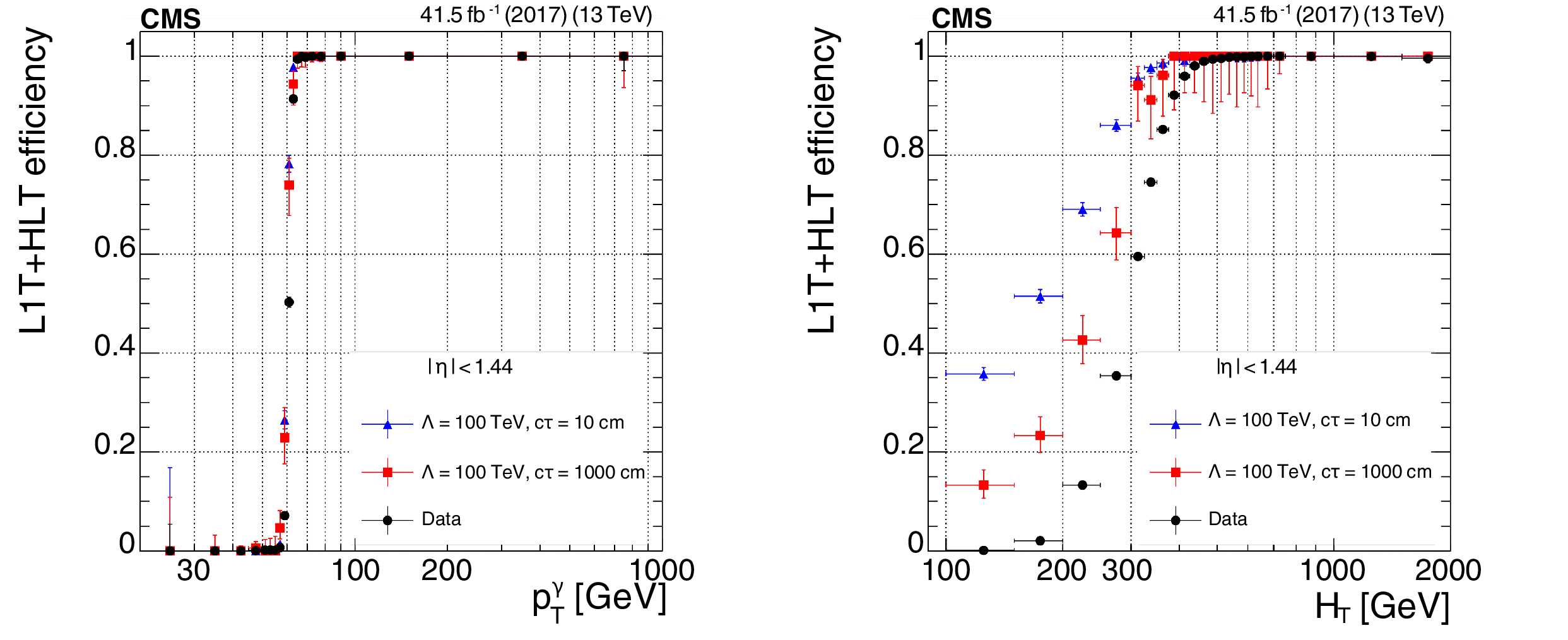

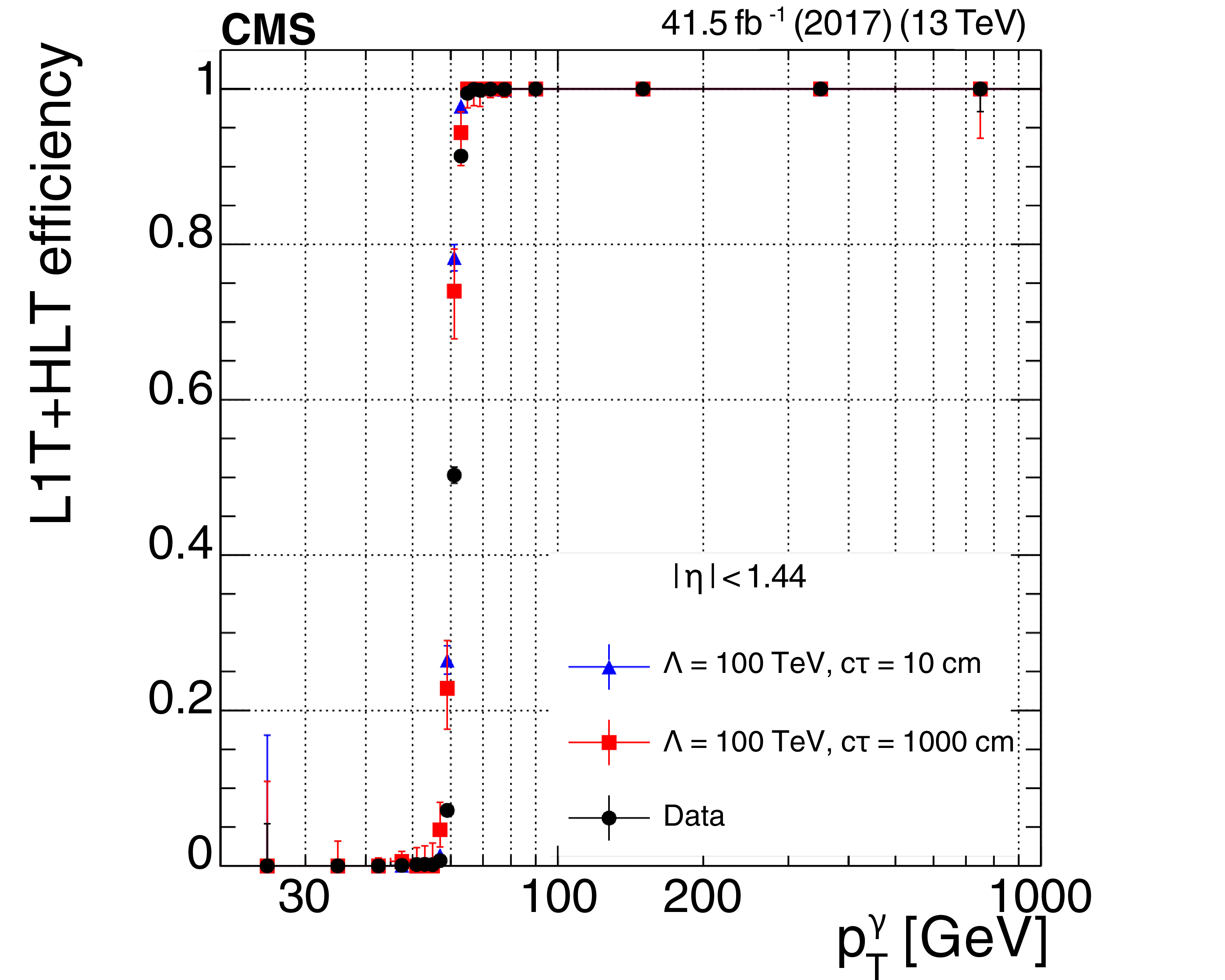

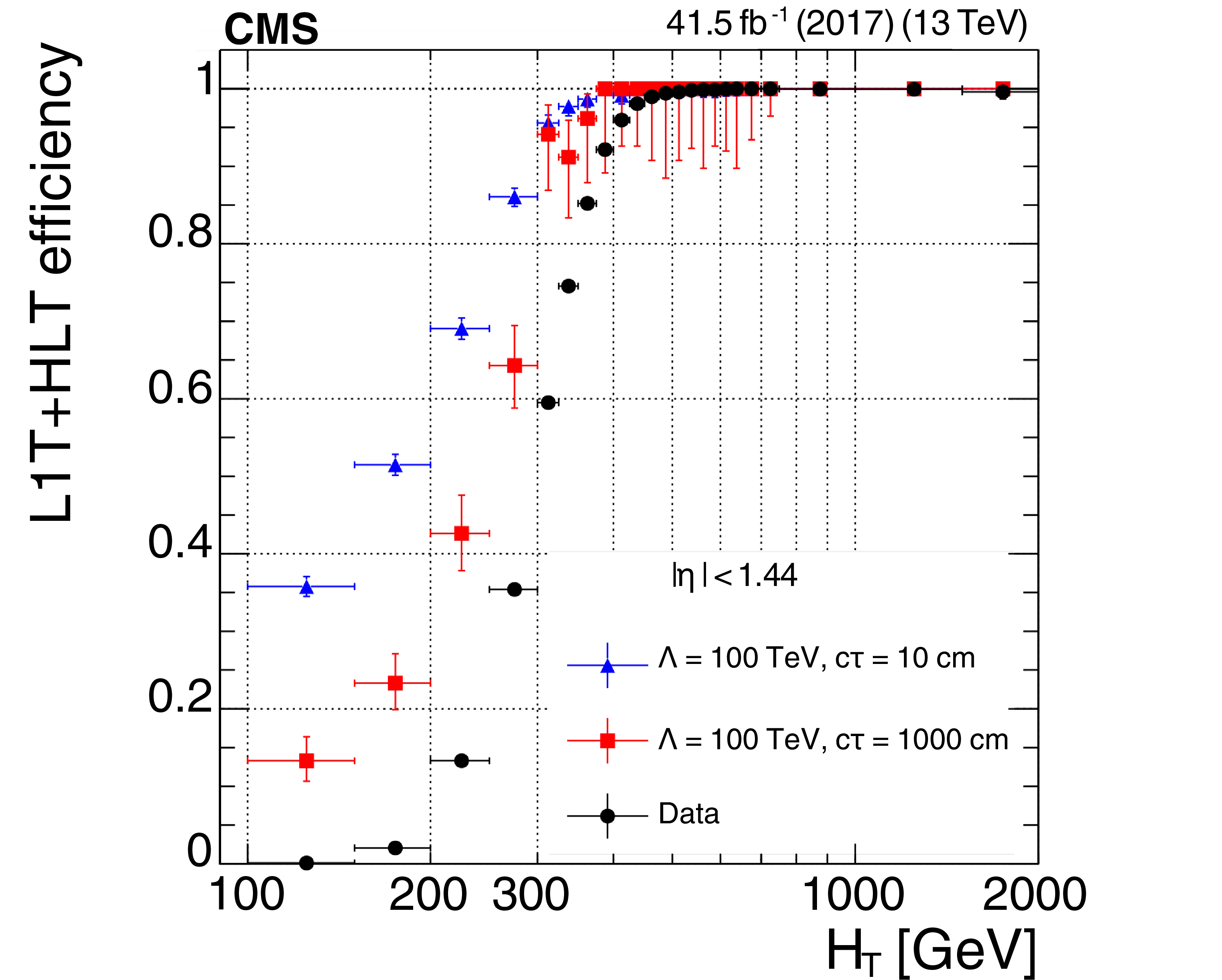

The L1T+HLT efficiency of the displaced-photon + $ H_{\mathrm{T}} $ trigger as a function of photon $ p_{\mathrm{T}} $ (left) and event $ H_{\mathrm{T}} $ (right), for 2017 data (black circles) and GMSB signals with $ \Lambda = $ 100 TeV and $ c\tau=10 \text{cm} $ (blue triangles) or $ c\tau=1000 \text{cm} $ (red squares). |

png pdf |

Figure 36-a:

The L1T+HLT efficiency of the displaced-photon + $ H_{\mathrm{T}} $ trigger as a function of photon $ p_{\mathrm{T}} $ (left) and event $ H_{\mathrm{T}} $ (right), for 2017 data (black circles) and GMSB signals with $ \Lambda = $ 100 TeV and $ c\tau=10 \text{cm} $ (blue triangles) or $ c\tau=1000 \text{cm} $ (red squares). |

png pdf |

Figure 36-b:

The L1T+HLT efficiency of the displaced-photon + $ H_{\mathrm{T}} $ trigger as a function of photon $ p_{\mathrm{T}} $ (left) and event $ H_{\mathrm{T}} $ (right), for 2017 data (black circles) and GMSB signals with $ \Lambda = $ 100 TeV and $ c\tau=10 \text{cm} $ (blue triangles) or $ c\tau=1000 \text{cm} $ (red squares). |

png pdf |

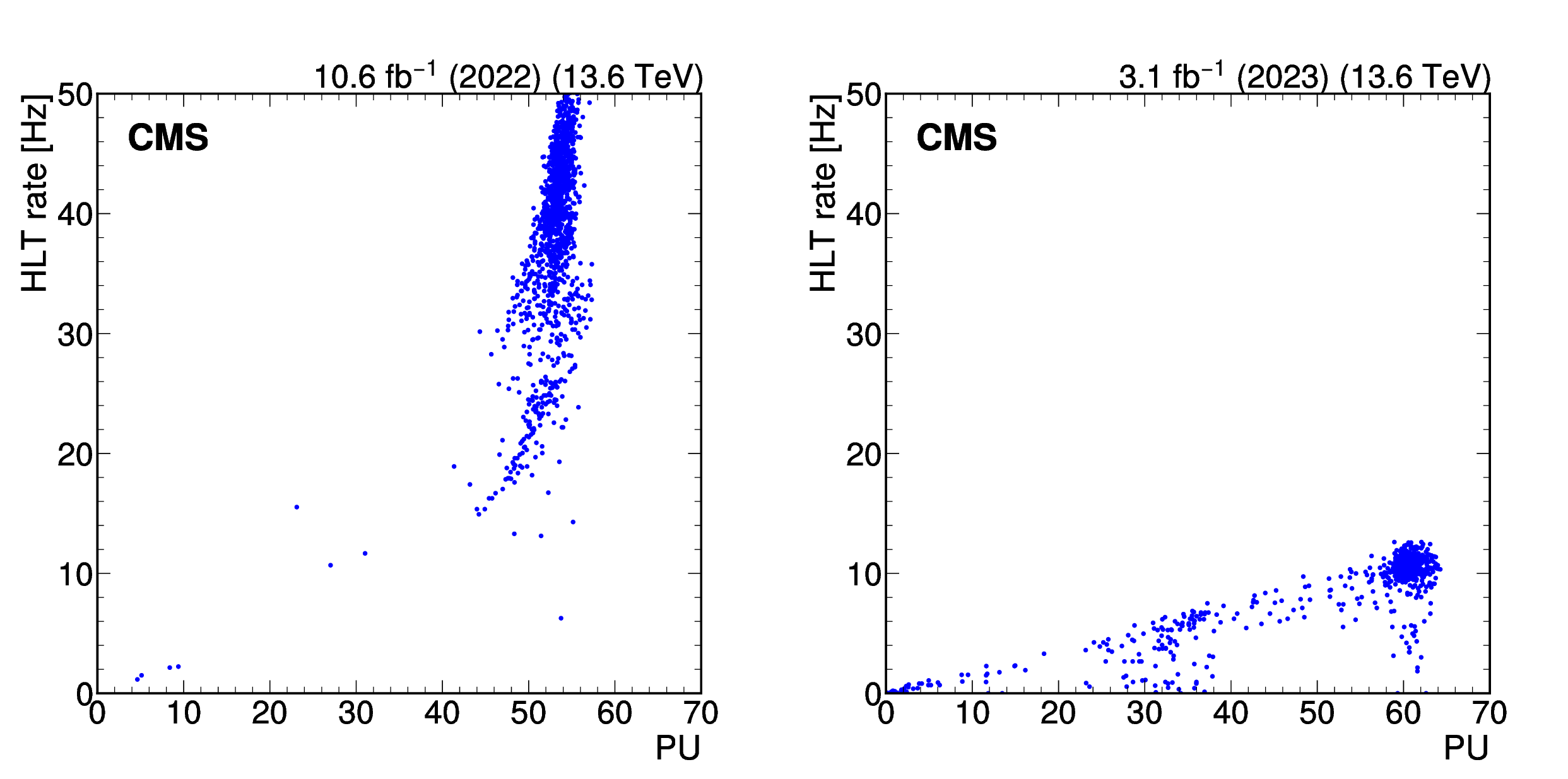

Figure 37:

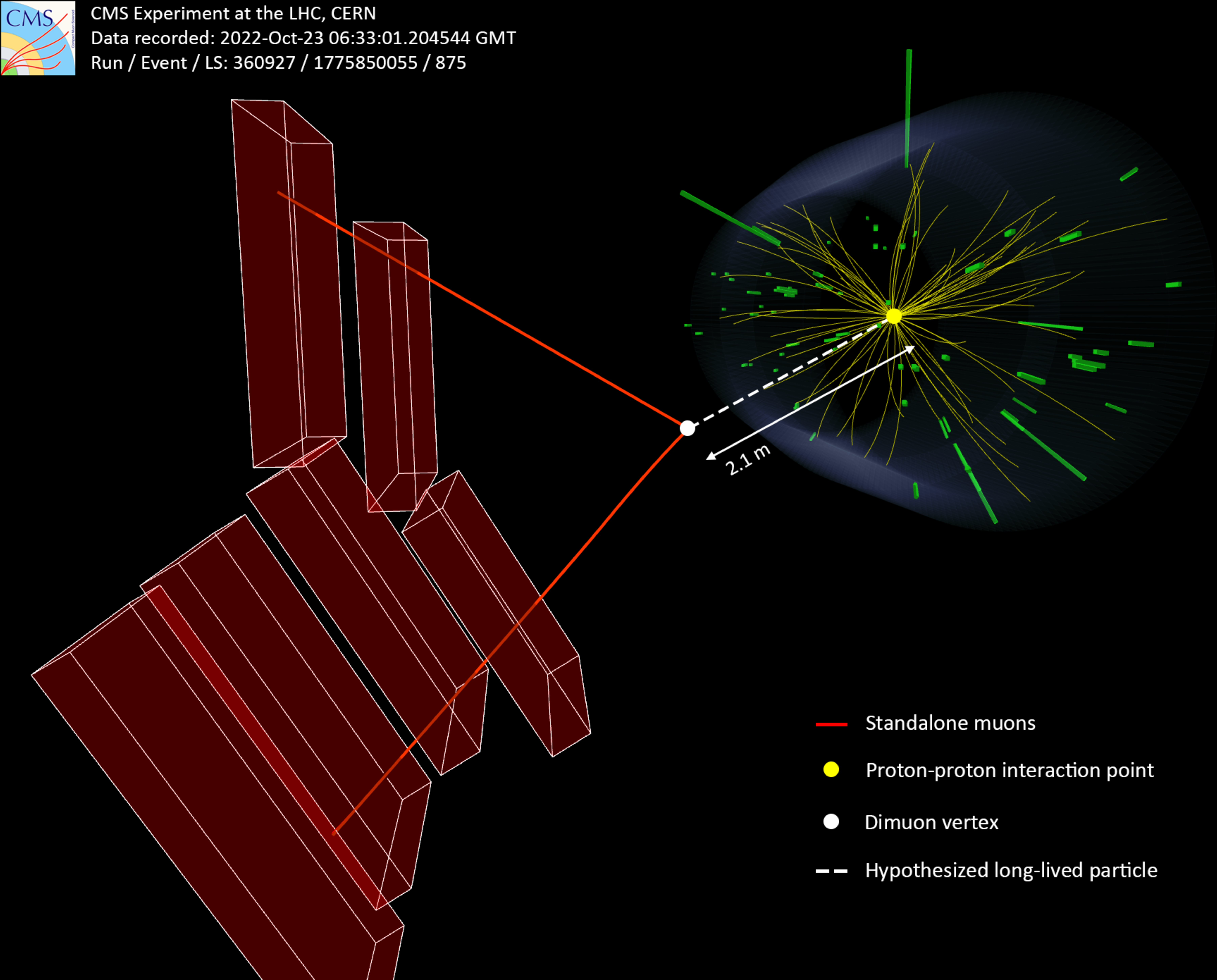

Total rate of the displaced-photon + $ H_{\mathrm{T}} $ HLT path for a few representative runs in 2022 data (left), at an instantaneous luminosity of approximately \instL1.8, and 2023 data (right), at an instantaneous luminosity of approximately \instL2.0, as a function of PU. The rate vs PU behavior was nonlinear in 2022, and the jet $ p_{\mathrm{T}} $ was increased to restore a linear dependence for 2023 data taking. |

png pdf |

Figure 37-a:

Total rate of the displaced-photon + $ H_{\mathrm{T}} $ HLT path for a few representative runs in 2022 data (left), at an instantaneous luminosity of approximately \instL1.8, and 2023 data (right), at an instantaneous luminosity of approximately \instL2.0, as a function of PU. The rate vs PU behavior was nonlinear in 2022, and the jet $ p_{\mathrm{T}} $ was increased to restore a linear dependence for 2023 data taking. |

png pdf |

Figure 37-b:

Total rate of the displaced-photon + $ H_{\mathrm{T}} $ HLT path for a few representative runs in 2022 data (left), at an instantaneous luminosity of approximately \instL1.8, and 2023 data (right), at an instantaneous luminosity of approximately \instL2.0, as a function of PU. The rate vs PU behavior was nonlinear in 2022, and the jet $ p_{\mathrm{T}} $ was increased to restore a linear dependence for 2023 data taking. |

png pdf |

Figure 38:

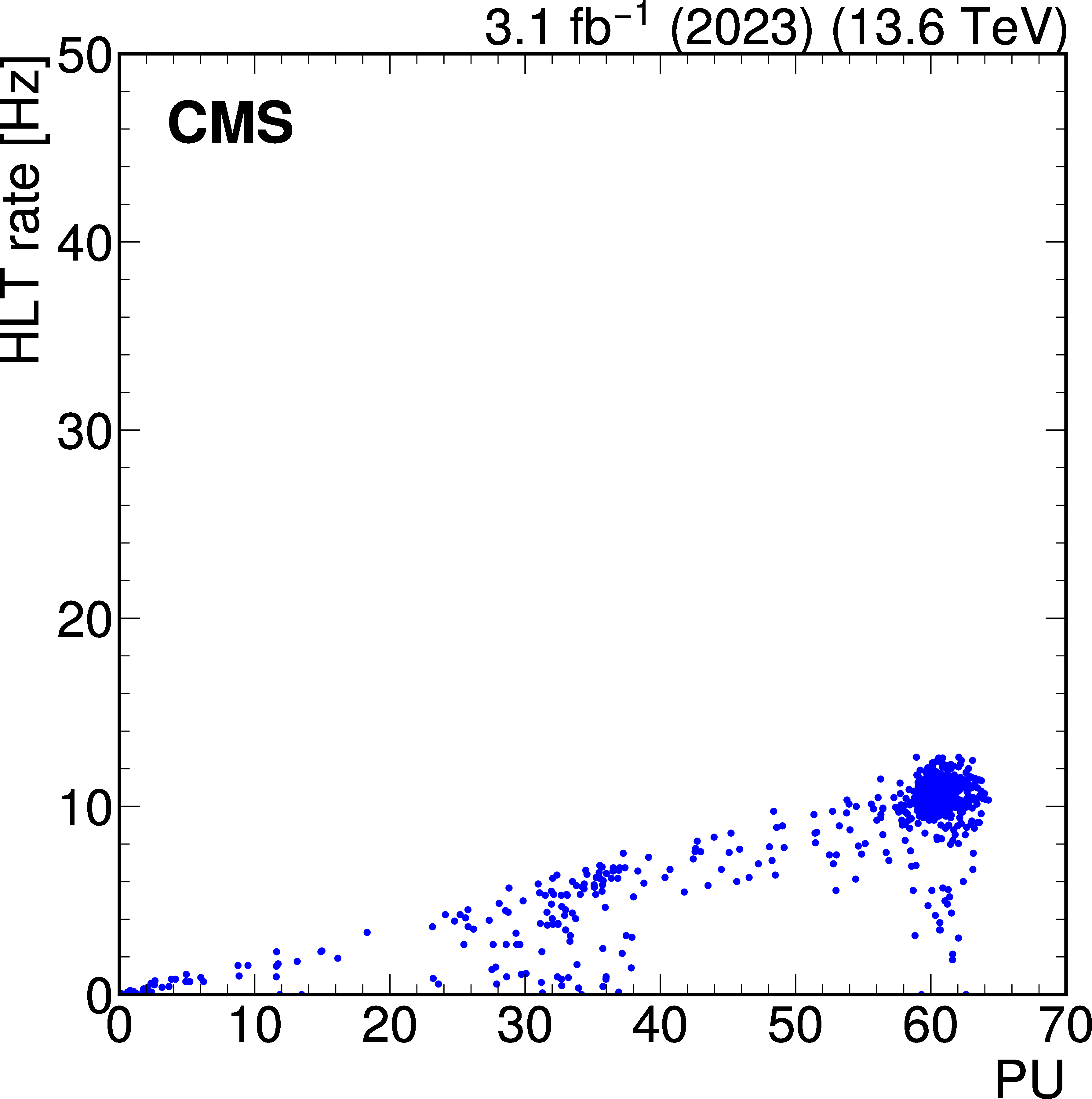

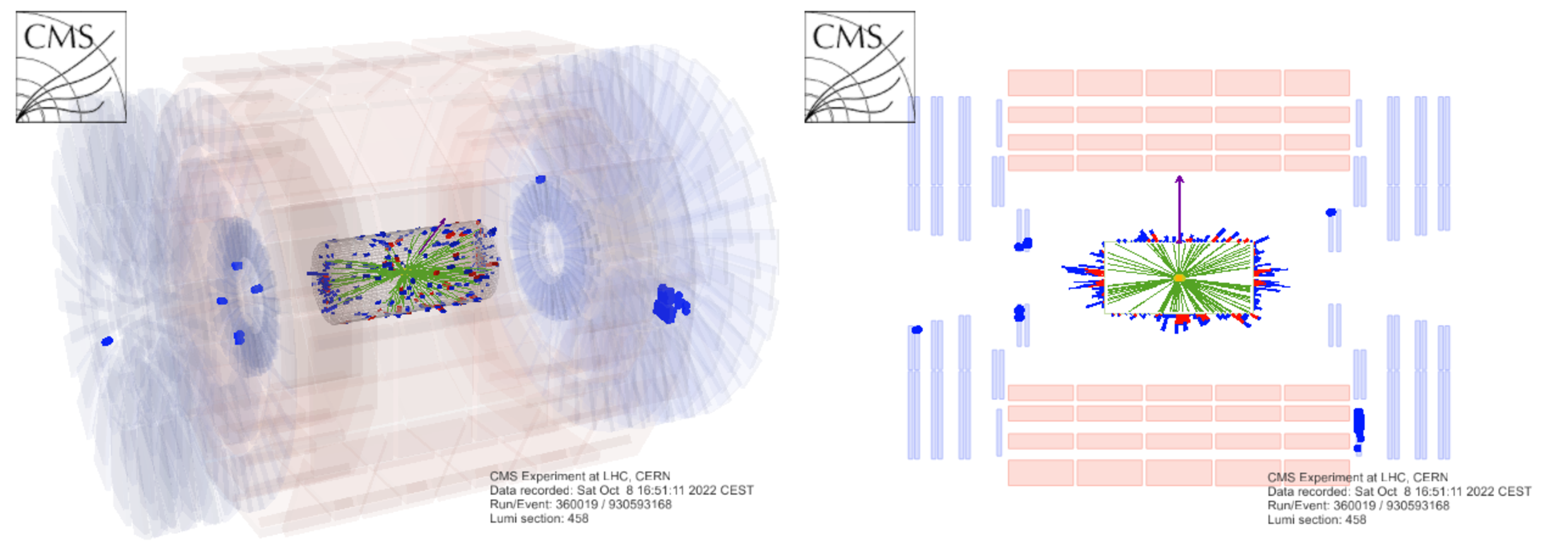

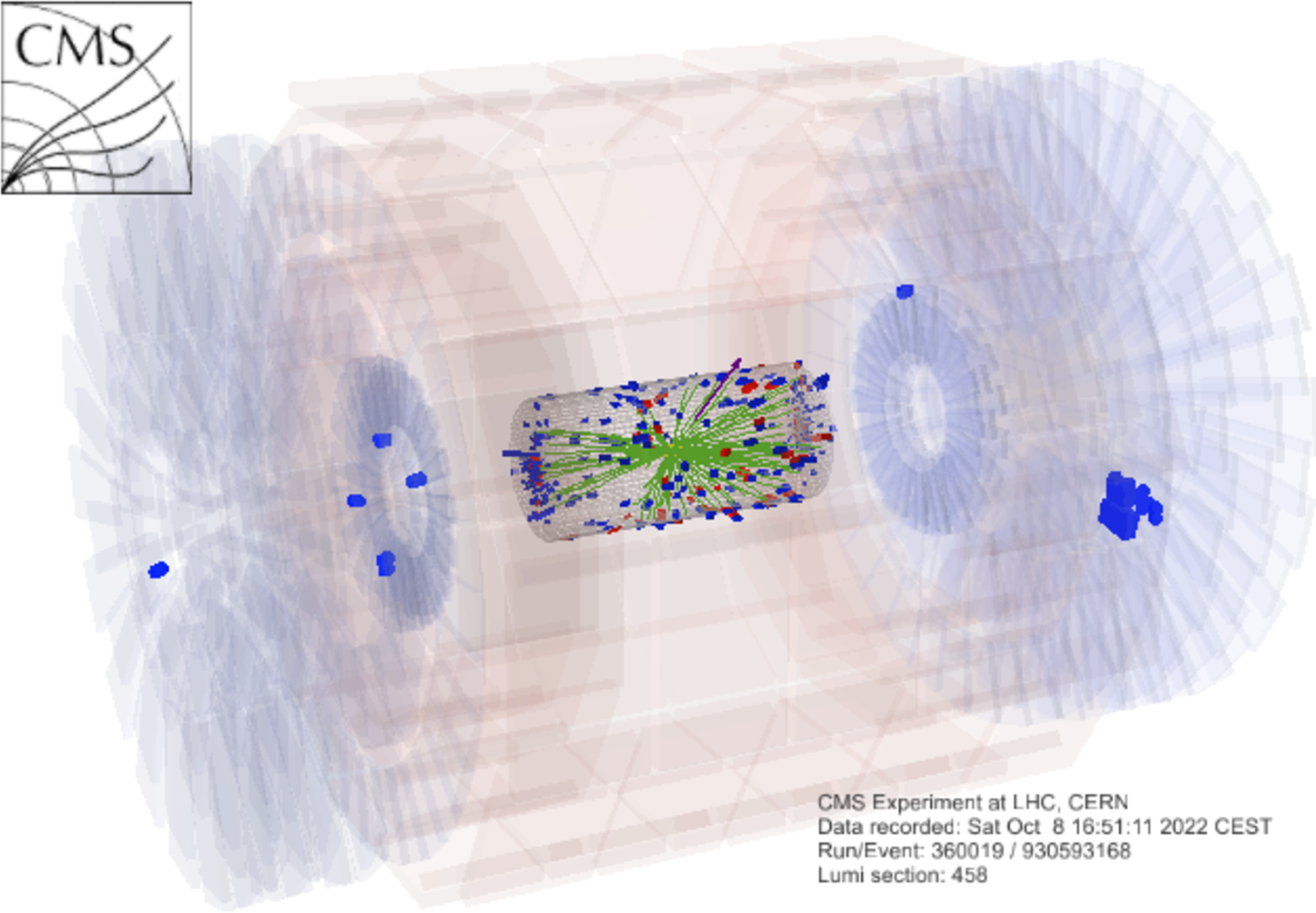

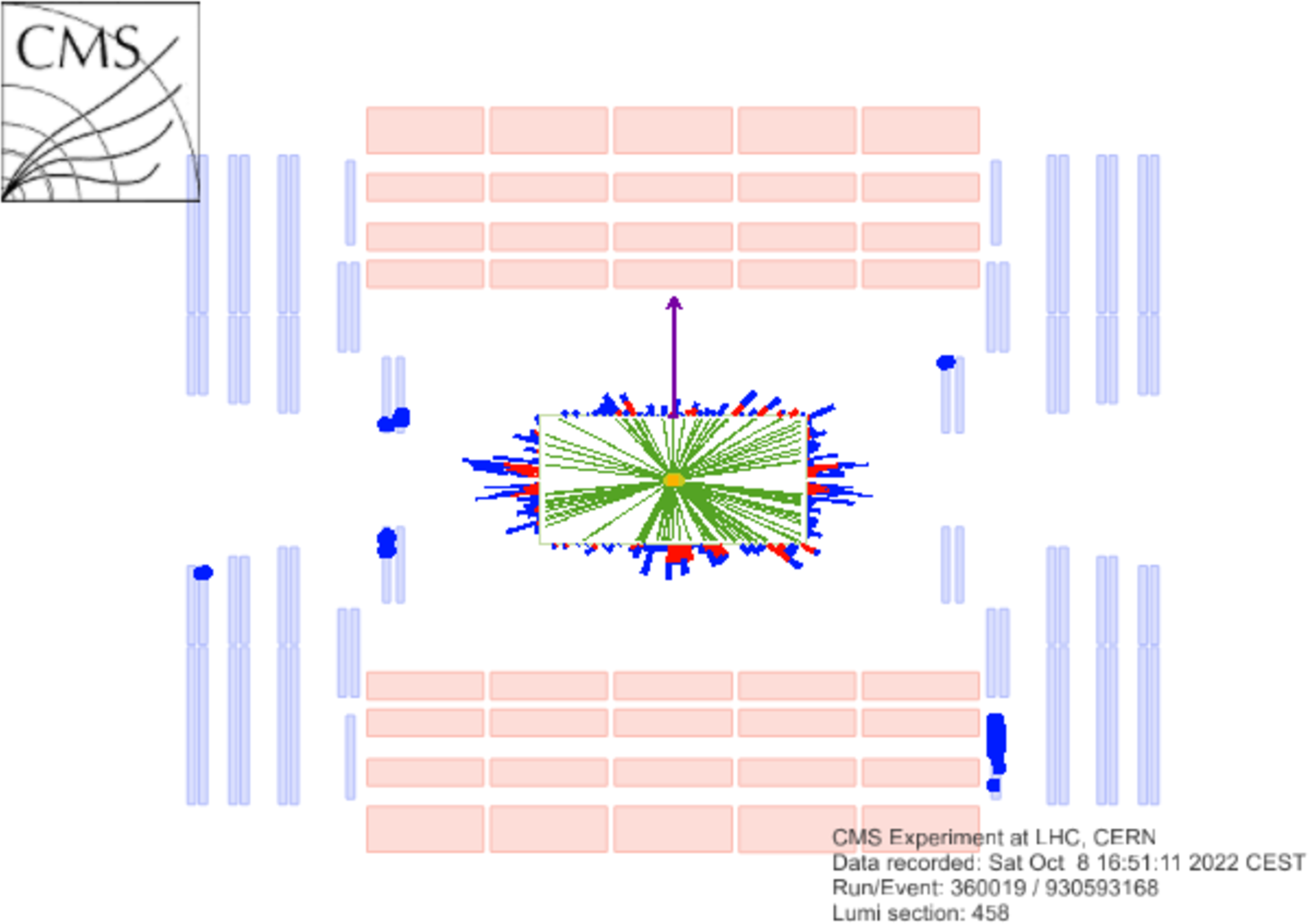

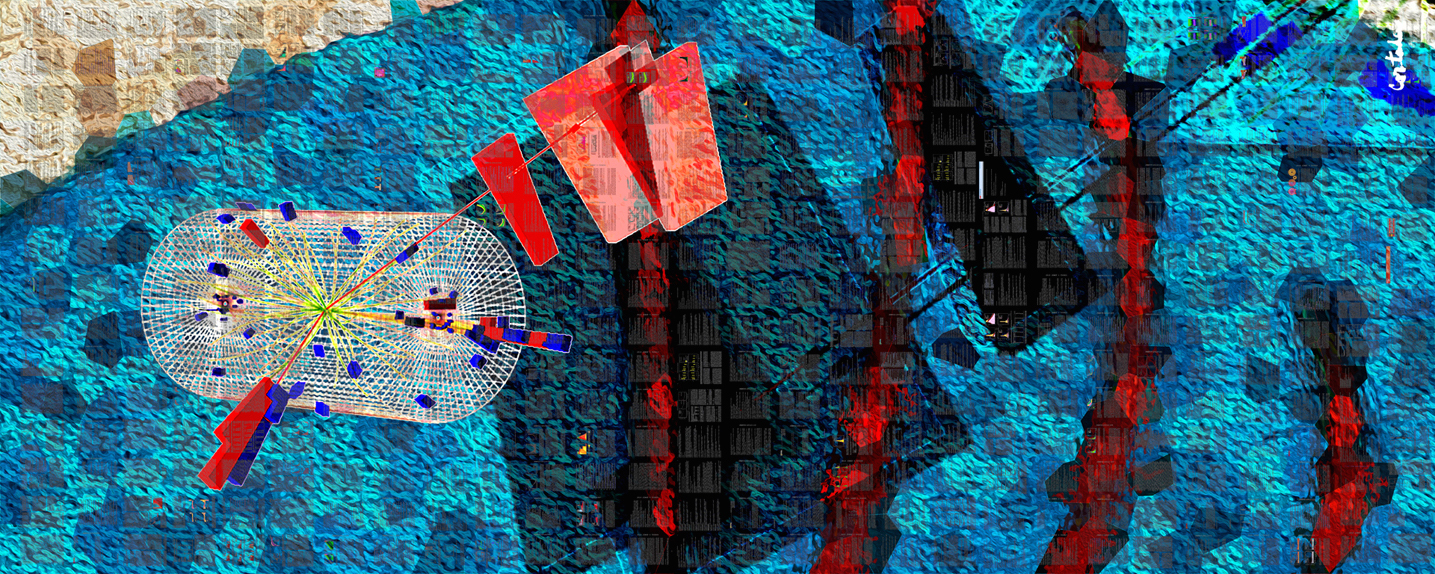

A Run 3 data event containing a candidate LLP decay into a pair of muons away from the IP, reconstructed in the CMS detector. The red lines correspond to the two muons, which are detected only in the muon system. The muon tracks are used to calculate a dimuon vertex, indicated by the white circle, where the LLP is hypothesized to have decayed. |

png pdf |

Figure 39:

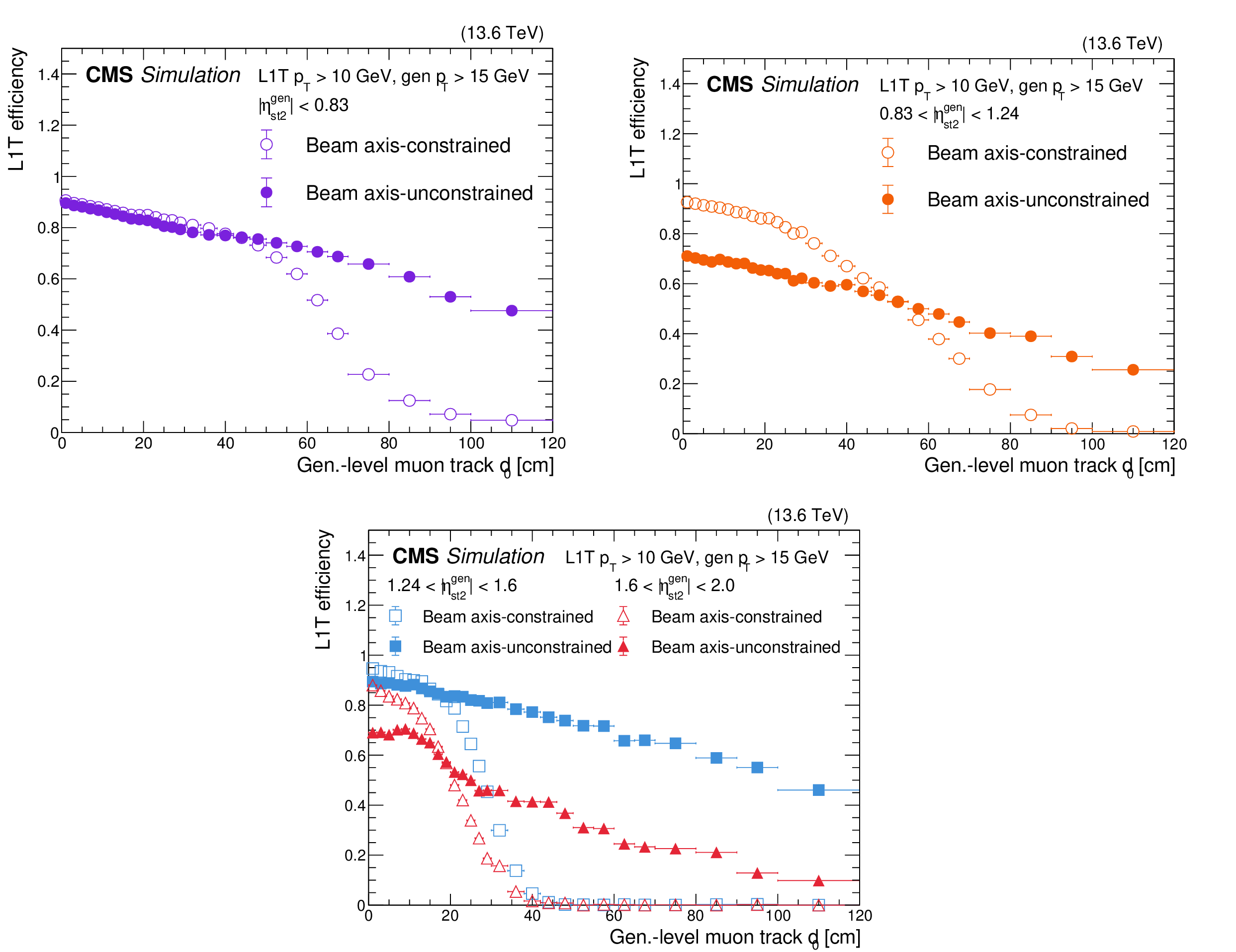

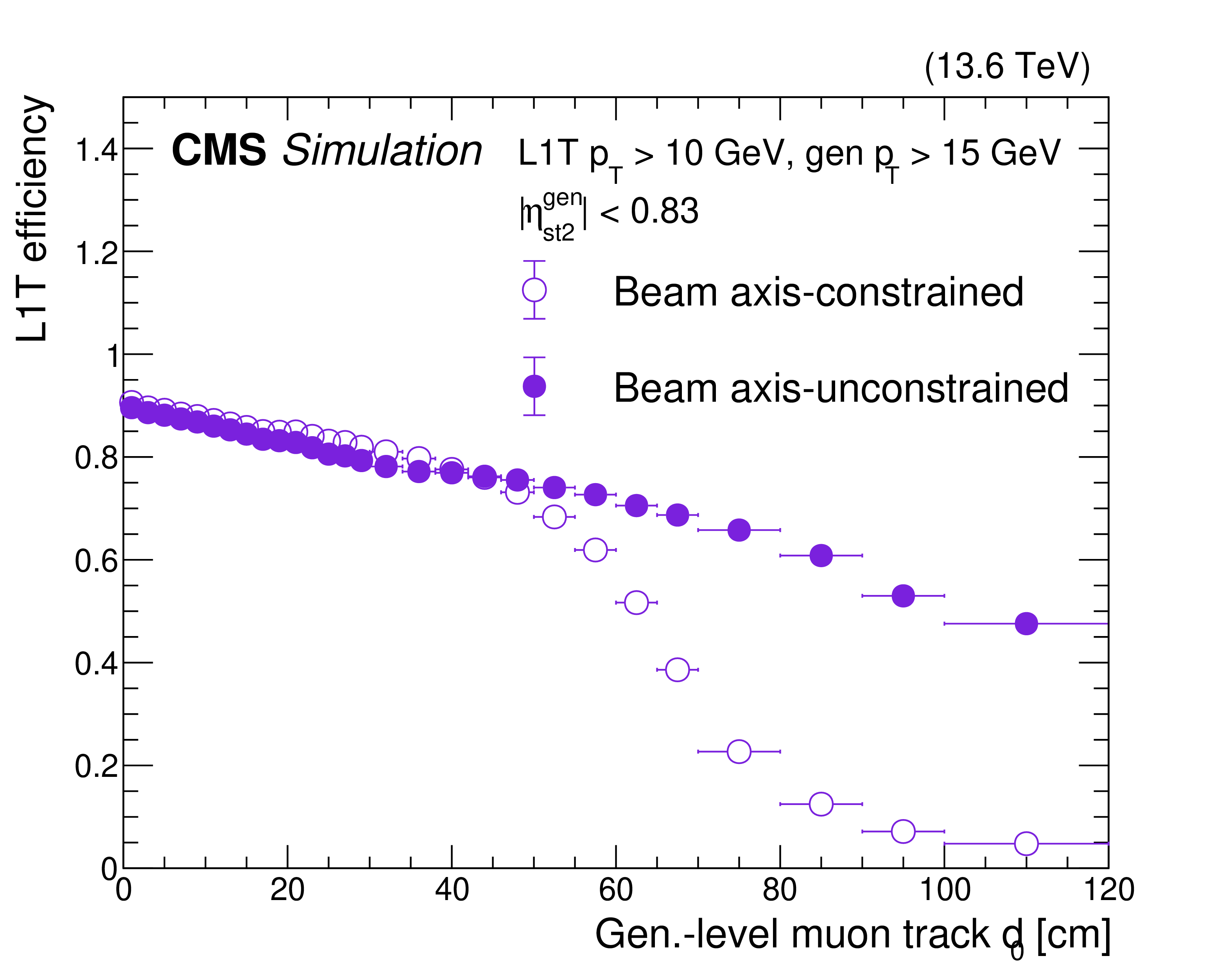

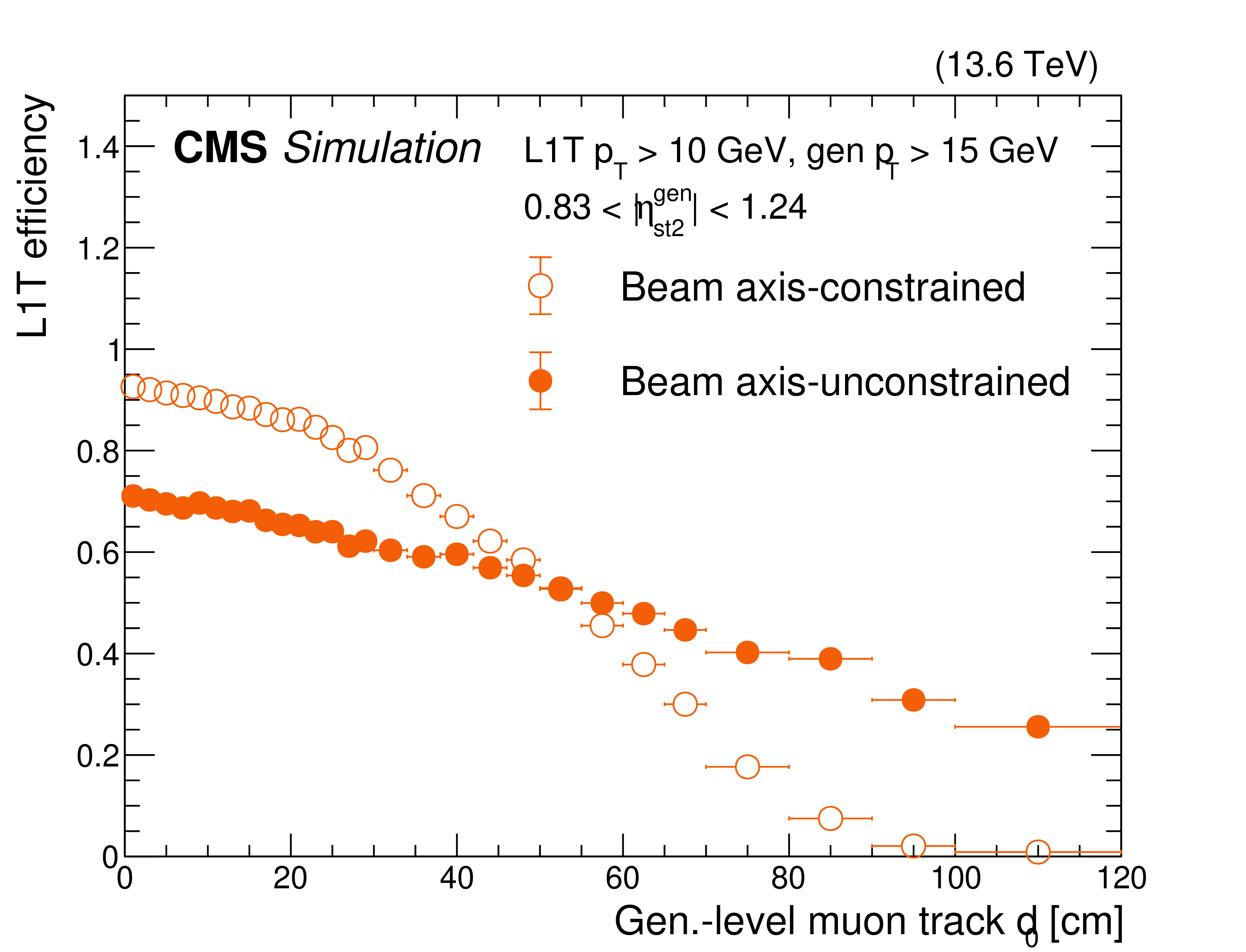

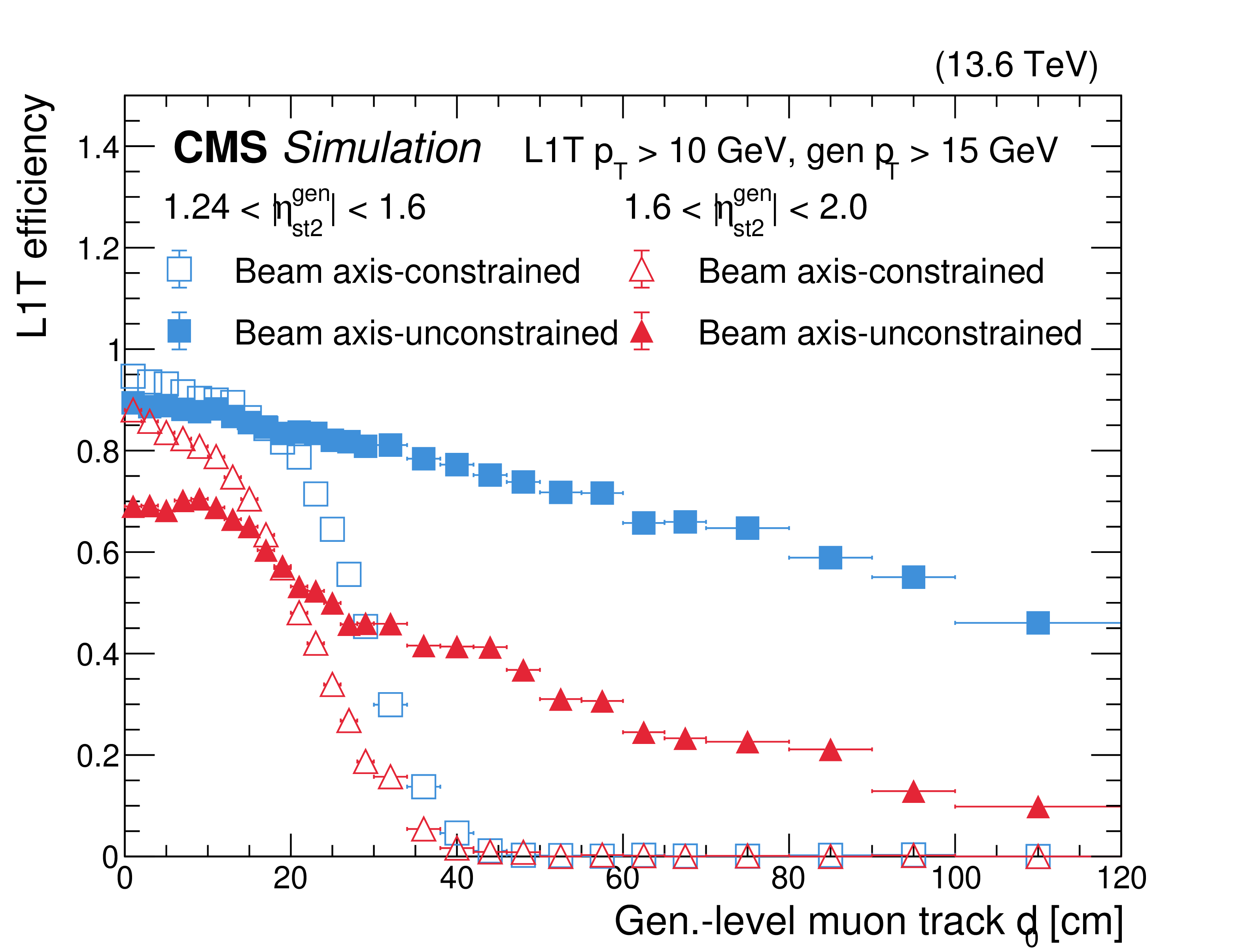

The BMTF (upper left), OMTF (upper right), and EMTF (lower) L1T efficiencies for beam axis-constrained (open circles, squares, and triangles) and beam axis-unconstrained (filled circles, squares, and triangles) $ p_{\mathrm{T}} $ assignment algorithms for L1T $ p_{\mathrm{T}} > $ 10 GeV with respect to generator-level muon track $ d_{\text{0}} $, obtained using a sample which produces LLPs that decay to dimuons. The L1T algorithms and data-taking conditions correspond to 2024. A selection on the generator-level muon track $ p_{\mathrm{T}} > $ 15 GeV is applied to show the performance at the efficiency plateau. The generator-level muon tracks are extrapolated to the second muon station to determine the $ \eta^{\text{gen}}_{\text{st2}} $ values that are used in the plot. Both the new vertex-unconstrained algorithm performance and the default beam axis-constrained algorithm performance are shown. In the EMTF plot, the different colors and symbols show different $ |\eta| $ regions: 1.24 $ < \eta^{\text{gen}}_{\text{st2}} < $ 1.6 (blue squares), 1.6 $ < \eta^{\text{gen}}_{\text{st2}} < $ 2.0 (red triangles). |

png pdf |

Figure 39-a:

The BMTF (upper left), OMTF (upper right), and EMTF (lower) L1T efficiencies for beam axis-constrained (open circles, squares, and triangles) and beam axis-unconstrained (filled circles, squares, and triangles) $ p_{\mathrm{T}} $ assignment algorithms for L1T $ p_{\mathrm{T}} > $ 10 GeV with respect to generator-level muon track $ d_{\text{0}} $, obtained using a sample which produces LLPs that decay to dimuons. The L1T algorithms and data-taking conditions correspond to 2024. A selection on the generator-level muon track $ p_{\mathrm{T}} > $ 15 GeV is applied to show the performance at the efficiency plateau. The generator-level muon tracks are extrapolated to the second muon station to determine the $ \eta^{\text{gen}}_{\text{st2}} $ values that are used in the plot. Both the new vertex-unconstrained algorithm performance and the default beam axis-constrained algorithm performance are shown. In the EMTF plot, the different colors and symbols show different $ |\eta| $ regions: 1.24 $ < \eta^{\text{gen}}_{\text{st2}} < $ 1.6 (blue squares), 1.6 $ < \eta^{\text{gen}}_{\text{st2}} < $ 2.0 (red triangles). |

png pdf |

Figure 39-b:

The BMTF (upper left), OMTF (upper right), and EMTF (lower) L1T efficiencies for beam axis-constrained (open circles, squares, and triangles) and beam axis-unconstrained (filled circles, squares, and triangles) $ p_{\mathrm{T}} $ assignment algorithms for L1T $ p_{\mathrm{T}} > $ 10 GeV with respect to generator-level muon track $ d_{\text{0}} $, obtained using a sample which produces LLPs that decay to dimuons. The L1T algorithms and data-taking conditions correspond to 2024. A selection on the generator-level muon track $ p_{\mathrm{T}} > $ 15 GeV is applied to show the performance at the efficiency plateau. The generator-level muon tracks are extrapolated to the second muon station to determine the $ \eta^{\text{gen}}_{\text{st2}} $ values that are used in the plot. Both the new vertex-unconstrained algorithm performance and the default beam axis-constrained algorithm performance are shown. In the EMTF plot, the different colors and symbols show different $ |\eta| $ regions: 1.24 $ < \eta^{\text{gen}}_{\text{st2}} < $ 1.6 (blue squares), 1.6 $ < \eta^{\text{gen}}_{\text{st2}} < $ 2.0 (red triangles). |

png pdf |

Figure 39-c:

The BMTF (upper left), OMTF (upper right), and EMTF (lower) L1T efficiencies for beam axis-constrained (open circles, squares, and triangles) and beam axis-unconstrained (filled circles, squares, and triangles) $ p_{\mathrm{T}} $ assignment algorithms for L1T $ p_{\mathrm{T}} > $ 10 GeV with respect to generator-level muon track $ d_{\text{0}} $, obtained using a sample which produces LLPs that decay to dimuons. The L1T algorithms and data-taking conditions correspond to 2024. A selection on the generator-level muon track $ p_{\mathrm{T}} > $ 15 GeV is applied to show the performance at the efficiency plateau. The generator-level muon tracks are extrapolated to the second muon station to determine the $ \eta^{\text{gen}}_{\text{st2}} $ values that are used in the plot. Both the new vertex-unconstrained algorithm performance and the default beam axis-constrained algorithm performance are shown. In the EMTF plot, the different colors and symbols show different $ |\eta| $ regions: 1.24 $ < \eta^{\text{gen}}_{\text{st2}} < $ 1.6 (blue squares), 1.6 $ < \eta^{\text{gen}}_{\text{st2}} < $ 2.0 (red triangles). |

png pdf |

Figure 40:

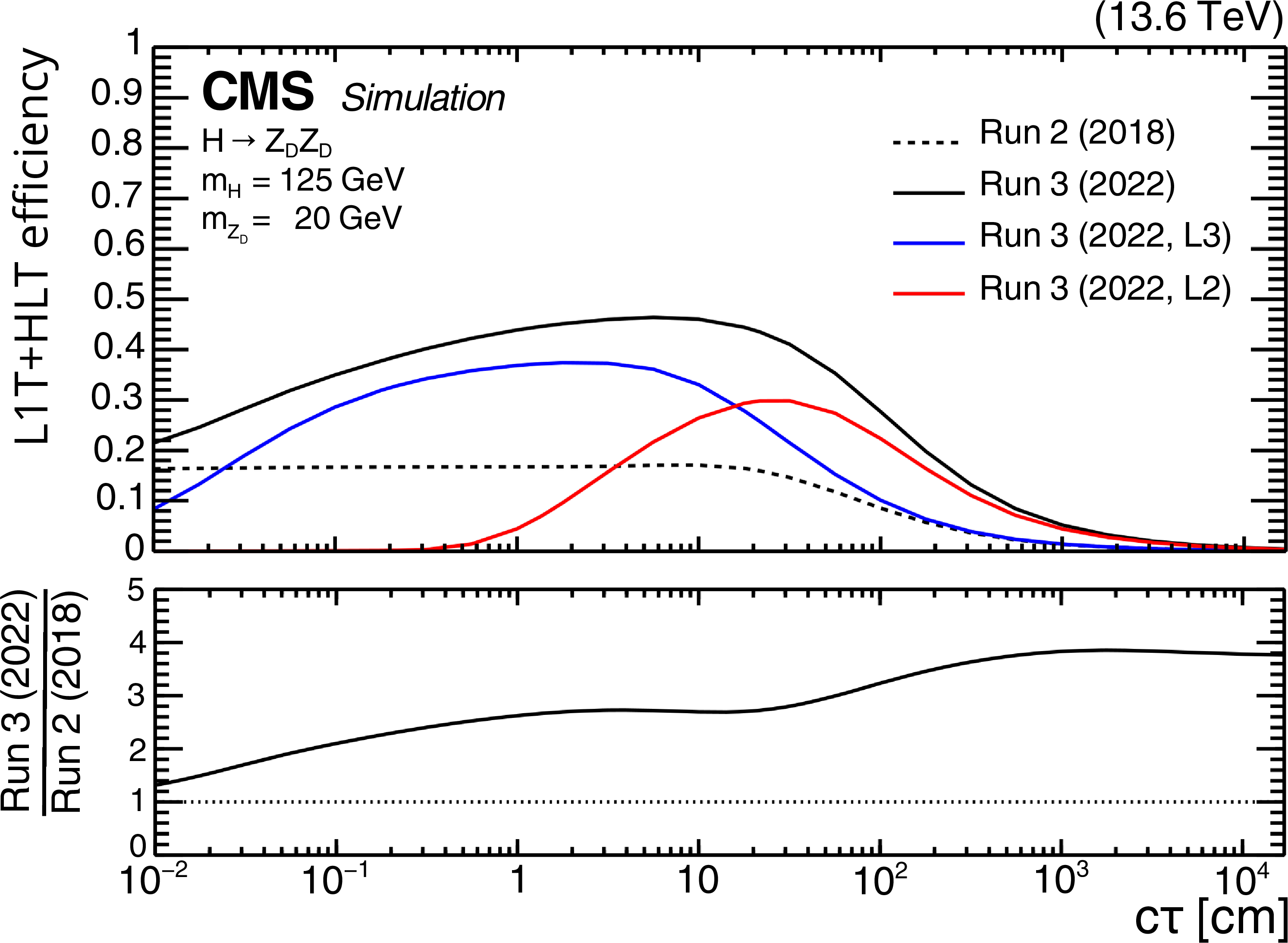

The L1T+HLT efficiencies of the various displaced-dimuon triggers and their logical OR as a function of $ c\tau $ for the HAHM signal events with $ m_{\mathrm{H}}= $ 125 GeV and $ m_{\mathrm{Z}_\text{D}} = $ 20 GeV, for 2022 conditions. The efficiency is defined as the fraction of simulated events that satisfy the detector acceptance and the requirements of the following sets of triggers: the Run 2 (2018) triggers (dashed black); the Run 3 (2022, L3) triggers (blue); the Run 3 (2022, L2) triggers (red); and the logical OR of all these triggers (Run 3 (2022), solid black). The lower panel shows the ratio of the overall Run 3 (2022) efficiency to the Run 2 (2018) efficiency. Figure adapted from Ref. [12]. |

png pdf |

Figure 41:

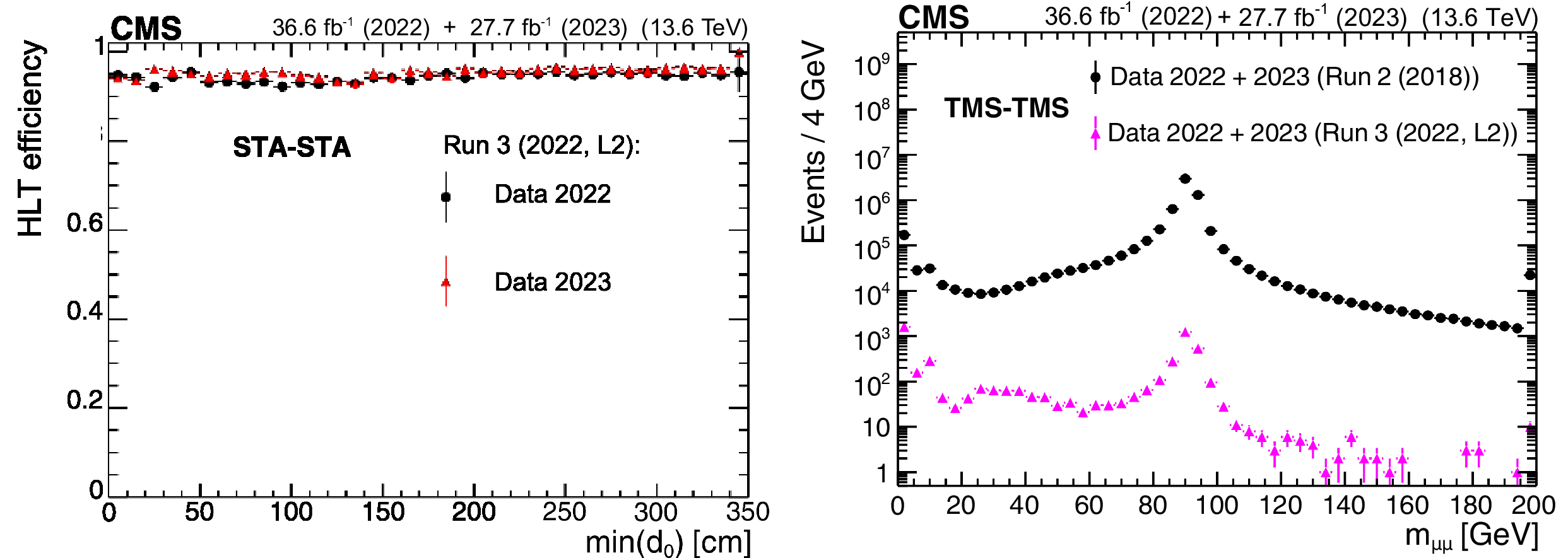

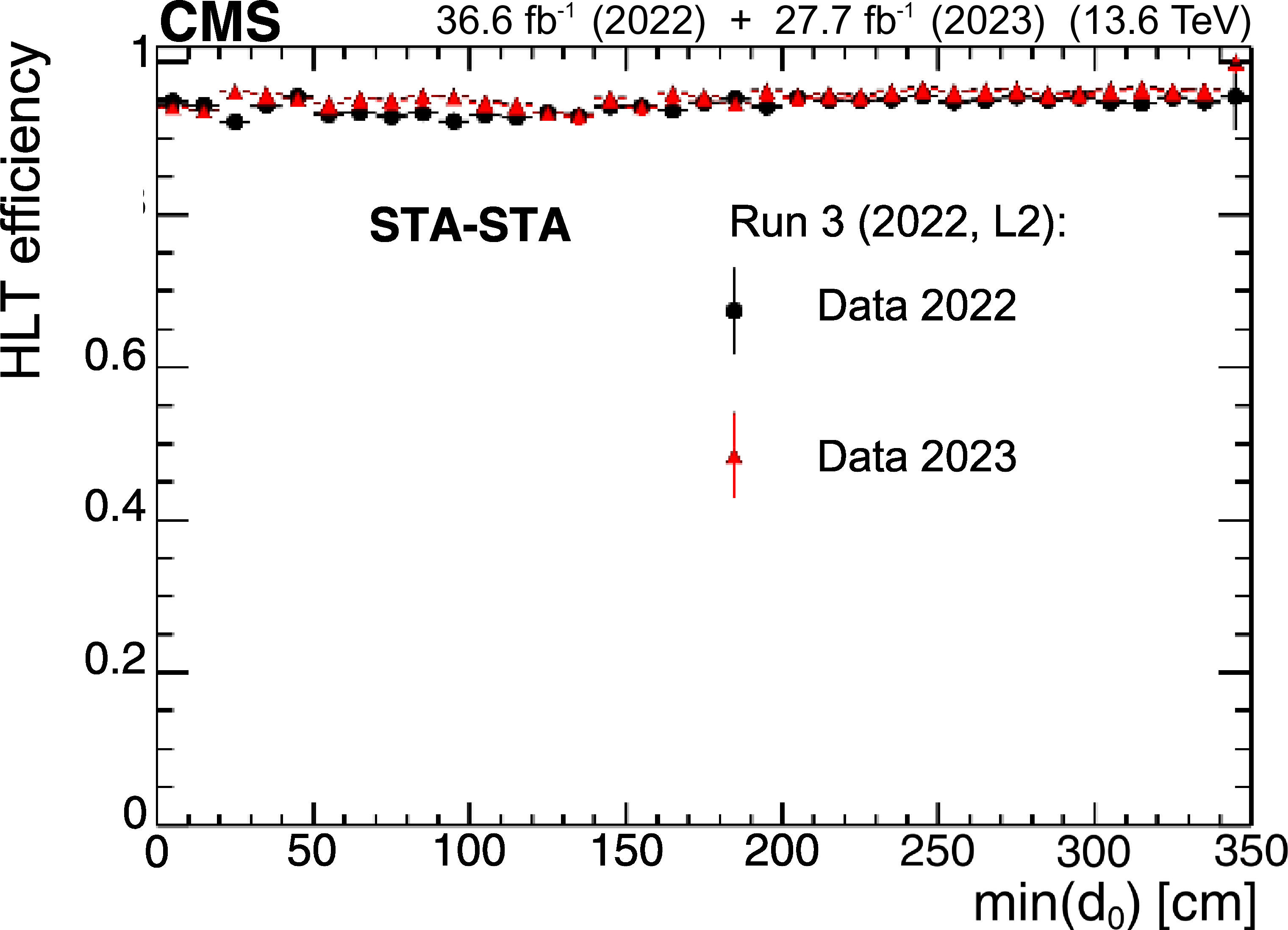

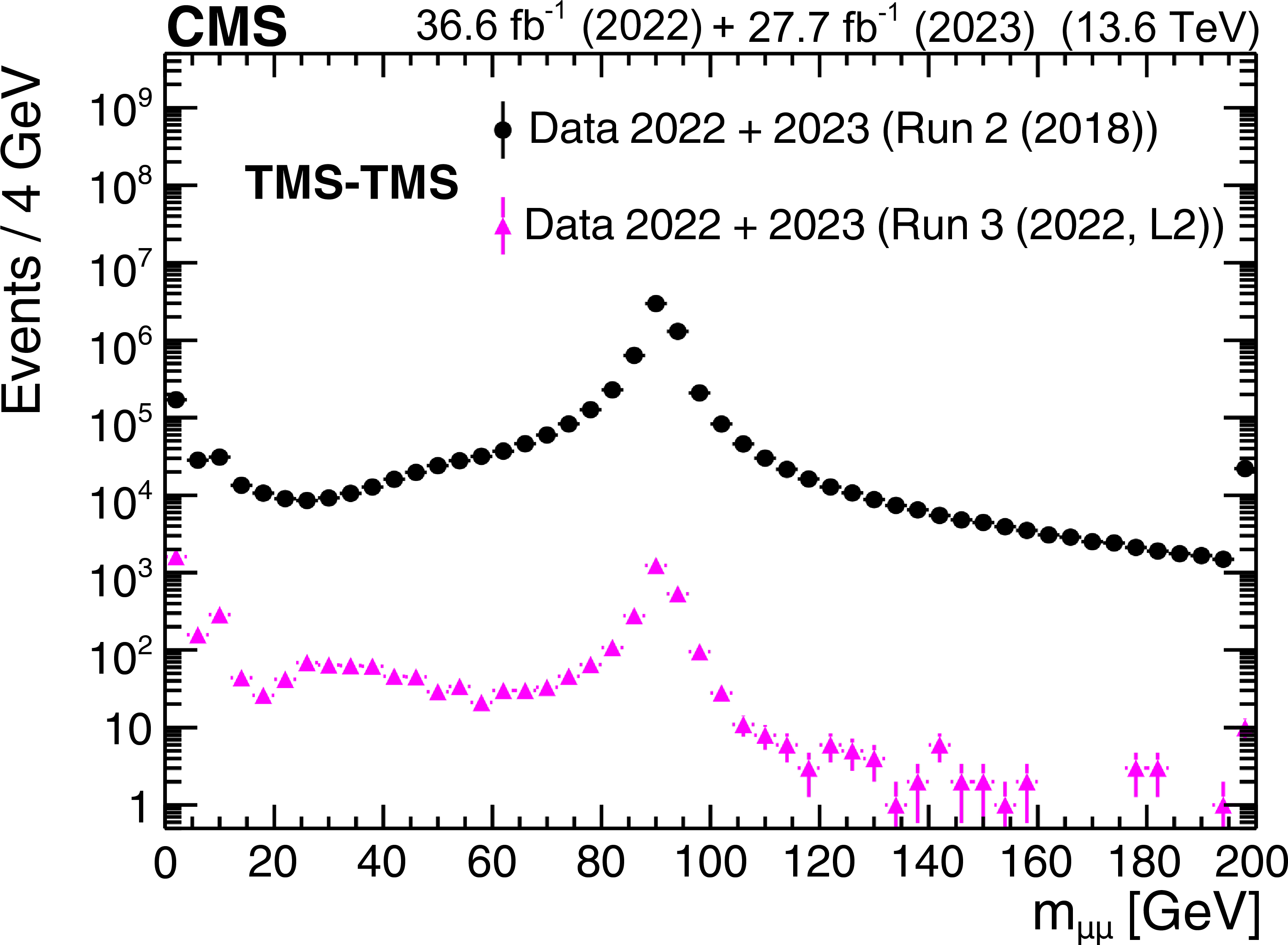

The HLT efficiency (left), defined as the fraction of events recorded by the Run 2 (2018) triggers that also satisfy the requirements of the Run 3 (2022, L2) triggers, as a function of offline-reconstructed $ \text{min}(d_{\text{0}}) $ of the two muons forming STA-STA dimuons in events enriched in cosmic ray muons. The black circles represent efficiencies during the 2022 data-taking period, and the red triangles represent the 2023 period. For displaced muons, the efficiency of the online $ \text{min}(d_{\text{0}}) $ requirement is larger than 95% in all data-taking periods. The invariant mass distribution for TMS-TMS dimuons (right) in events recorded by the Run 2 (2018) triggers in the combined 2022 and 2023 data set (black circles), and in the subset of events also selected by the Run 3 (2022, L2) triggers (pink triangles), illustrating the prompt muon rejection of the Run 3 (2022, L2) triggers. |

png pdf |

Figure 41-a:

The HLT efficiency (left), defined as the fraction of events recorded by the Run 2 (2018) triggers that also satisfy the requirements of the Run 3 (2022, L2) triggers, as a function of offline-reconstructed $ \text{min}(d_{\text{0}}) $ of the two muons forming STA-STA dimuons in events enriched in cosmic ray muons. The black circles represent efficiencies during the 2022 data-taking period, and the red triangles represent the 2023 period. For displaced muons, the efficiency of the online $ \text{min}(d_{\text{0}}) $ requirement is larger than 95% in all data-taking periods. The invariant mass distribution for TMS-TMS dimuons (right) in events recorded by the Run 2 (2018) triggers in the combined 2022 and 2023 data set (black circles), and in the subset of events also selected by the Run 3 (2022, L2) triggers (pink triangles), illustrating the prompt muon rejection of the Run 3 (2022, L2) triggers. |

png pdf |

Figure 41-b:

The HLT efficiency (left), defined as the fraction of events recorded by the Run 2 (2018) triggers that also satisfy the requirements of the Run 3 (2022, L2) triggers, as a function of offline-reconstructed $ \text{min}(d_{\text{0}}) $ of the two muons forming STA-STA dimuons in events enriched in cosmic ray muons. The black circles represent efficiencies during the 2022 data-taking period, and the red triangles represent the 2023 period. For displaced muons, the efficiency of the online $ \text{min}(d_{\text{0}}) $ requirement is larger than 95% in all data-taking periods. The invariant mass distribution for TMS-TMS dimuons (right) in events recorded by the Run 2 (2018) triggers in the combined 2022 and 2023 data set (black circles), and in the subset of events also selected by the Run 3 (2022, L2) triggers (pink triangles), illustrating the prompt muon rejection of the Run 3 (2022, L2) triggers. |

png pdf |

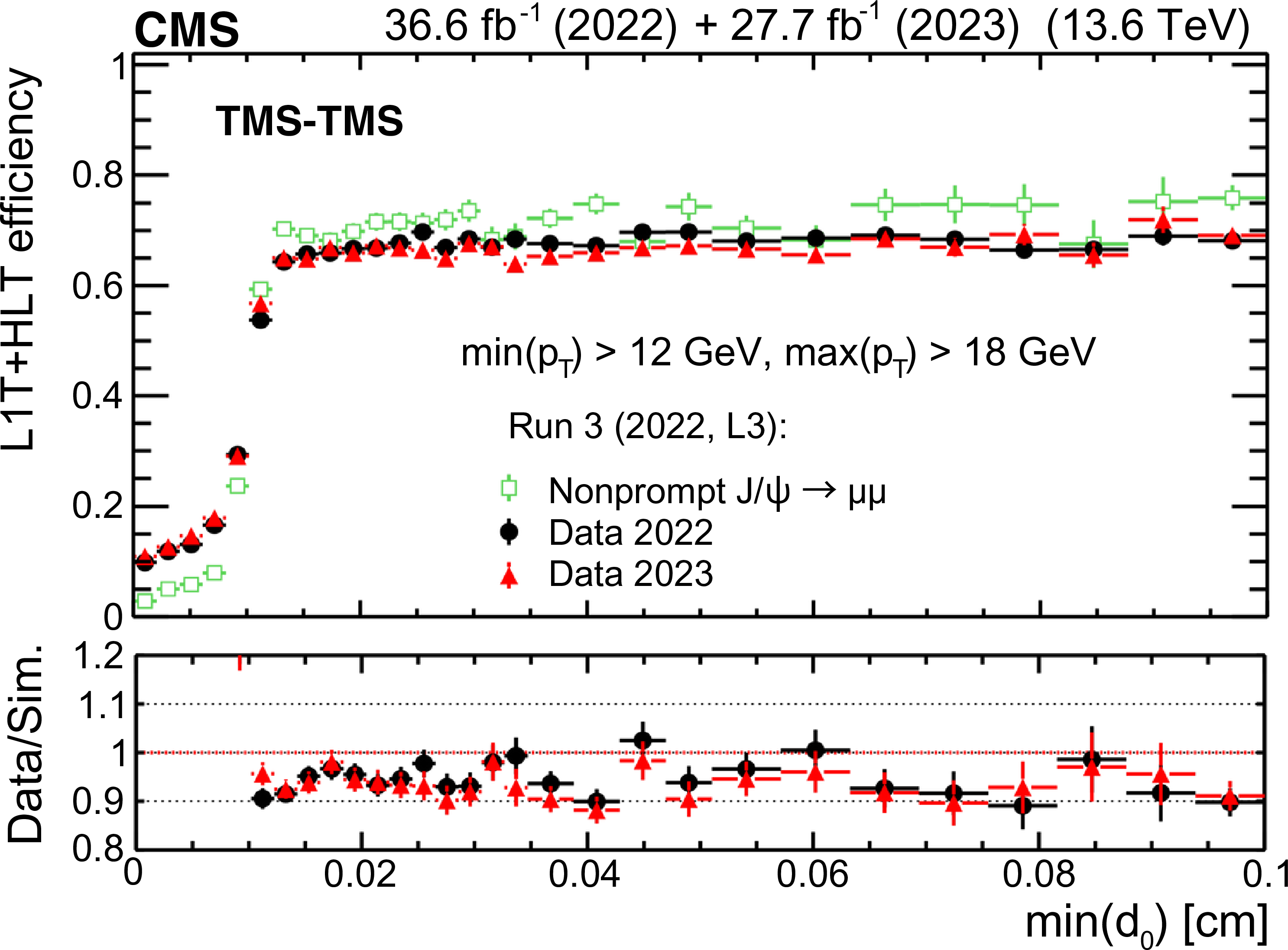

Figure 42:

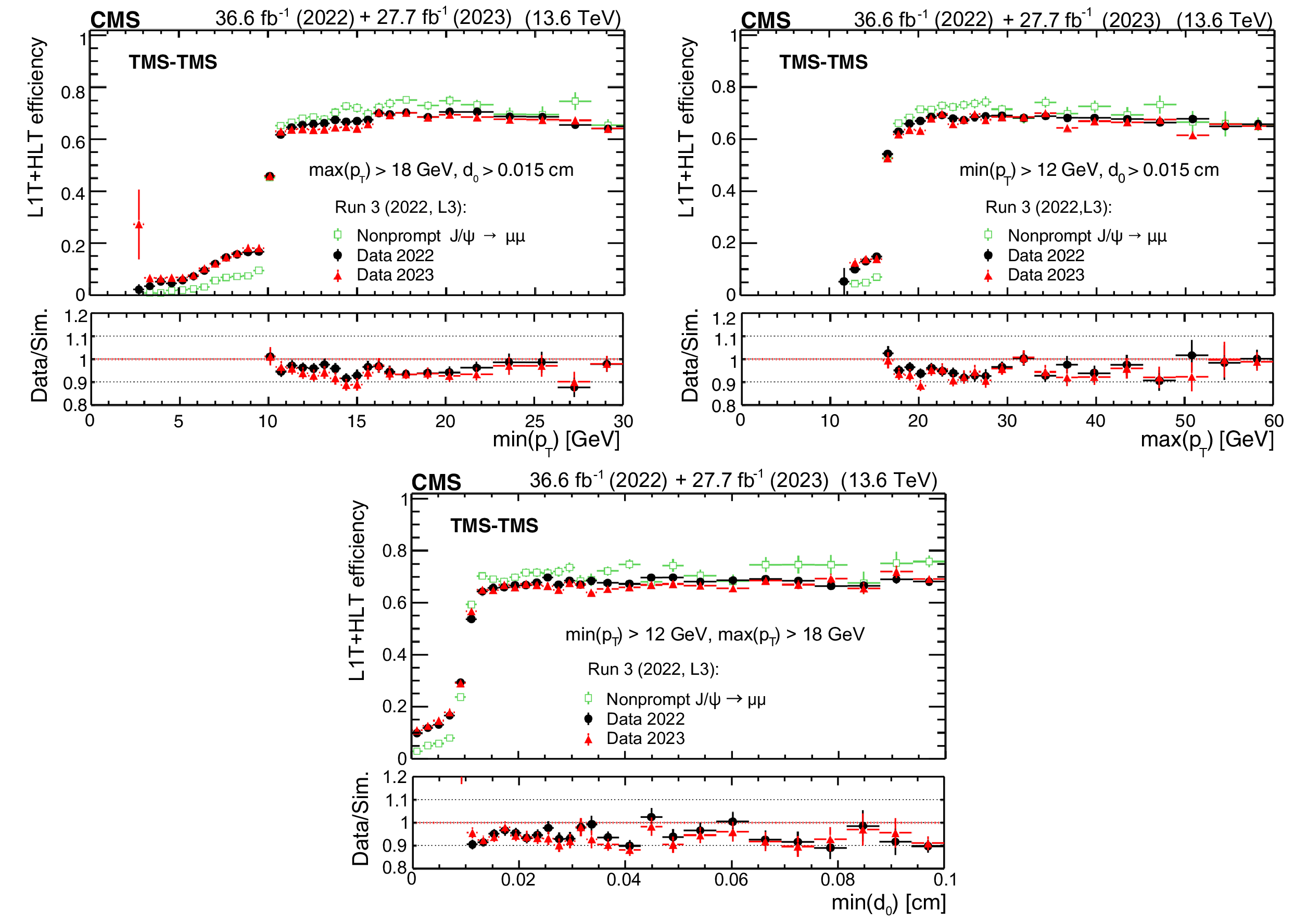

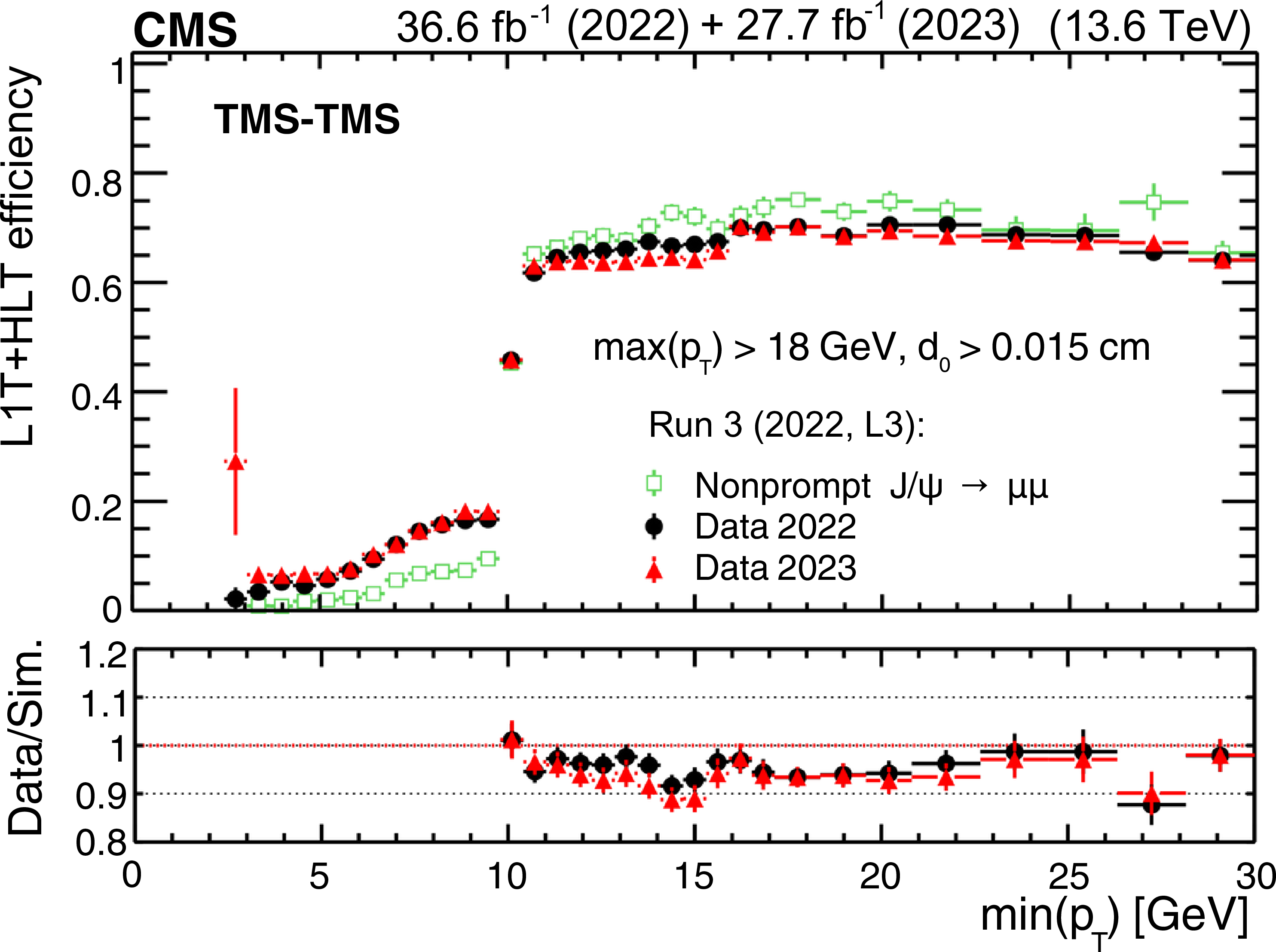

The L1T+HLT efficiency of the Run 3 (2022, L3) triggers in 2022 data (filled black circles), 2023 data (filled red triangles), and simulation (open green squares) as a function of $ \text{min}(p_{\mathrm{T}}) $ (upper left), $ \text{max}(p_{\mathrm{T}}) $ (upper right), and $ \text{min}(d_{\text{0}}) $ (lower) of the two muons forming TMS-TMS dimuons in events enriched in $ \mathrm{J}/\psi\to\mu\mu $ events. The efficiency in data is the fraction of $ \mathrm{J}/\psi\to\mu\mu $ events recorded by the triggers based on the information from jets and $ p_{\mathrm{T}}^\text{miss} $ that also satisfy the requirements of the Run 3 (2022, L3) triggers. It is compared to the efficiency of the Run 3 (2022, L3) triggers in a combination of simulated samples of $ \mathrm{J}/\psi\to\mu\mu $ events produced in various b hadron decays. The lower panels show the ratio of the data to simulated events. |

png pdf |

Figure 42-a:

The L1T+HLT efficiency of the Run 3 (2022, L3) triggers in 2022 data (filled black circles), 2023 data (filled red triangles), and simulation (open green squares) as a function of $ \text{min}(p_{\mathrm{T}}) $ (upper left), $ \text{max}(p_{\mathrm{T}}) $ (upper right), and $ \text{min}(d_{\text{0}}) $ (lower) of the two muons forming TMS-TMS dimuons in events enriched in $ \mathrm{J}/\psi\to\mu\mu $ events. The efficiency in data is the fraction of $ \mathrm{J}/\psi\to\mu\mu $ events recorded by the triggers based on the information from jets and $ p_{\mathrm{T}}^\text{miss} $ that also satisfy the requirements of the Run 3 (2022, L3) triggers. It is compared to the efficiency of the Run 3 (2022, L3) triggers in a combination of simulated samples of $ \mathrm{J}/\psi\to\mu\mu $ events produced in various b hadron decays. The lower panels show the ratio of the data to simulated events. |

png pdf |

Figure 42-b:

The L1T+HLT efficiency of the Run 3 (2022, L3) triggers in 2022 data (filled black circles), 2023 data (filled red triangles), and simulation (open green squares) as a function of $ \text{min}(p_{\mathrm{T}}) $ (upper left), $ \text{max}(p_{\mathrm{T}}) $ (upper right), and $ \text{min}(d_{\text{0}}) $ (lower) of the two muons forming TMS-TMS dimuons in events enriched in $ \mathrm{J}/\psi\to\mu\mu $ events. The efficiency in data is the fraction of $ \mathrm{J}/\psi\to\mu\mu $ events recorded by the triggers based on the information from jets and $ p_{\mathrm{T}}^\text{miss} $ that also satisfy the requirements of the Run 3 (2022, L3) triggers. It is compared to the efficiency of the Run 3 (2022, L3) triggers in a combination of simulated samples of $ \mathrm{J}/\psi\to\mu\mu $ events produced in various b hadron decays. The lower panels show the ratio of the data to simulated events. |

png pdf |

Figure 42-c:

The L1T+HLT efficiency of the Run 3 (2022, L3) triggers in 2022 data (filled black circles), 2023 data (filled red triangles), and simulation (open green squares) as a function of $ \text{min}(p_{\mathrm{T}}) $ (upper left), $ \text{max}(p_{\mathrm{T}}) $ (upper right), and $ \text{min}(d_{\text{0}}) $ (lower) of the two muons forming TMS-TMS dimuons in events enriched in $ \mathrm{J}/\psi\to\mu\mu $ events. The efficiency in data is the fraction of $ \mathrm{J}/\psi\to\mu\mu $ events recorded by the triggers based on the information from jets and $ p_{\mathrm{T}}^\text{miss} $ that also satisfy the requirements of the Run 3 (2022, L3) triggers. It is compared to the efficiency of the Run 3 (2022, L3) triggers in a combination of simulated samples of $ \mathrm{J}/\psi\to\mu\mu $ events produced in various b hadron decays. The lower panels show the ratio of the data to simulated events. |

png pdf |

Figure 43:

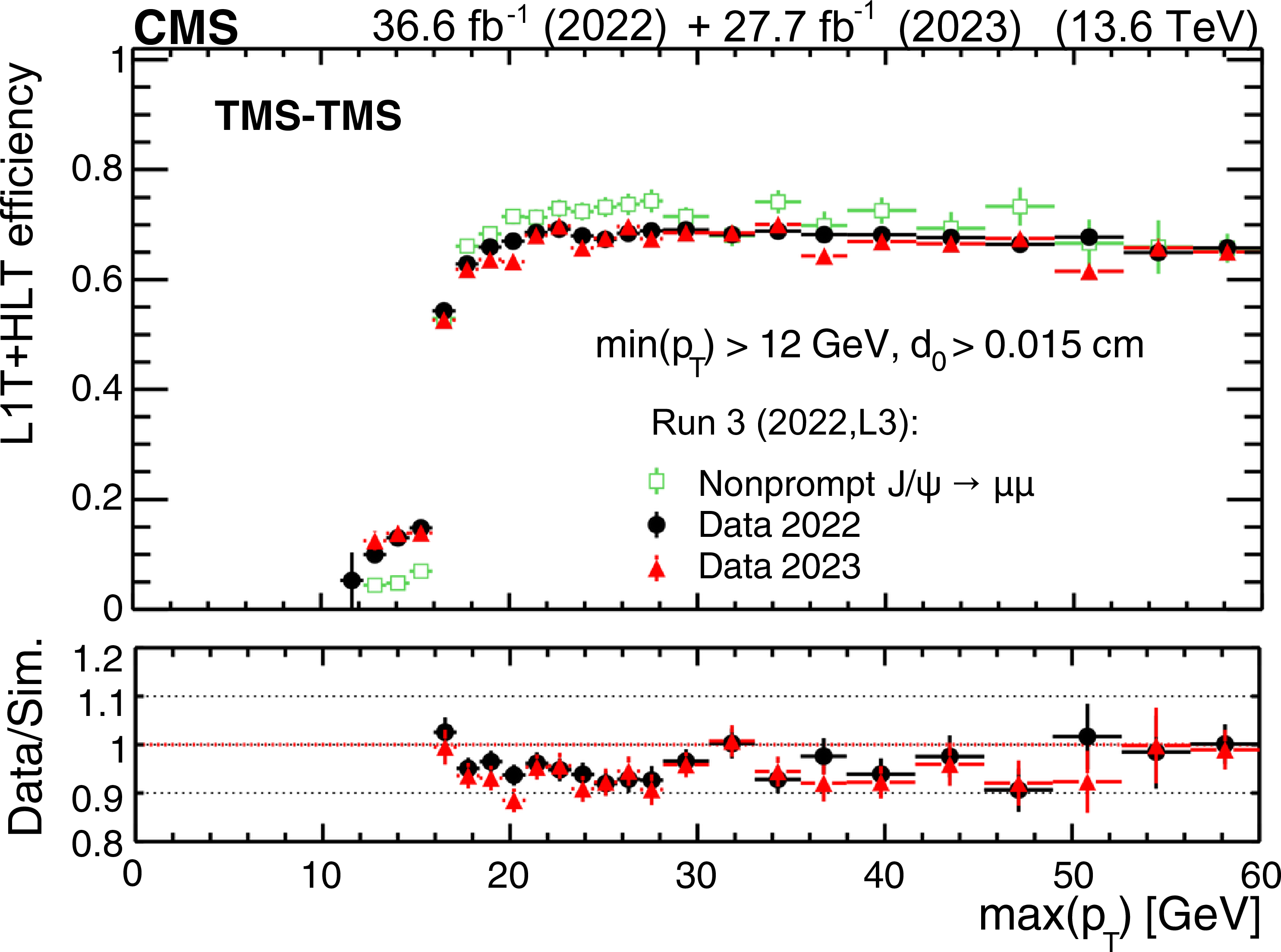

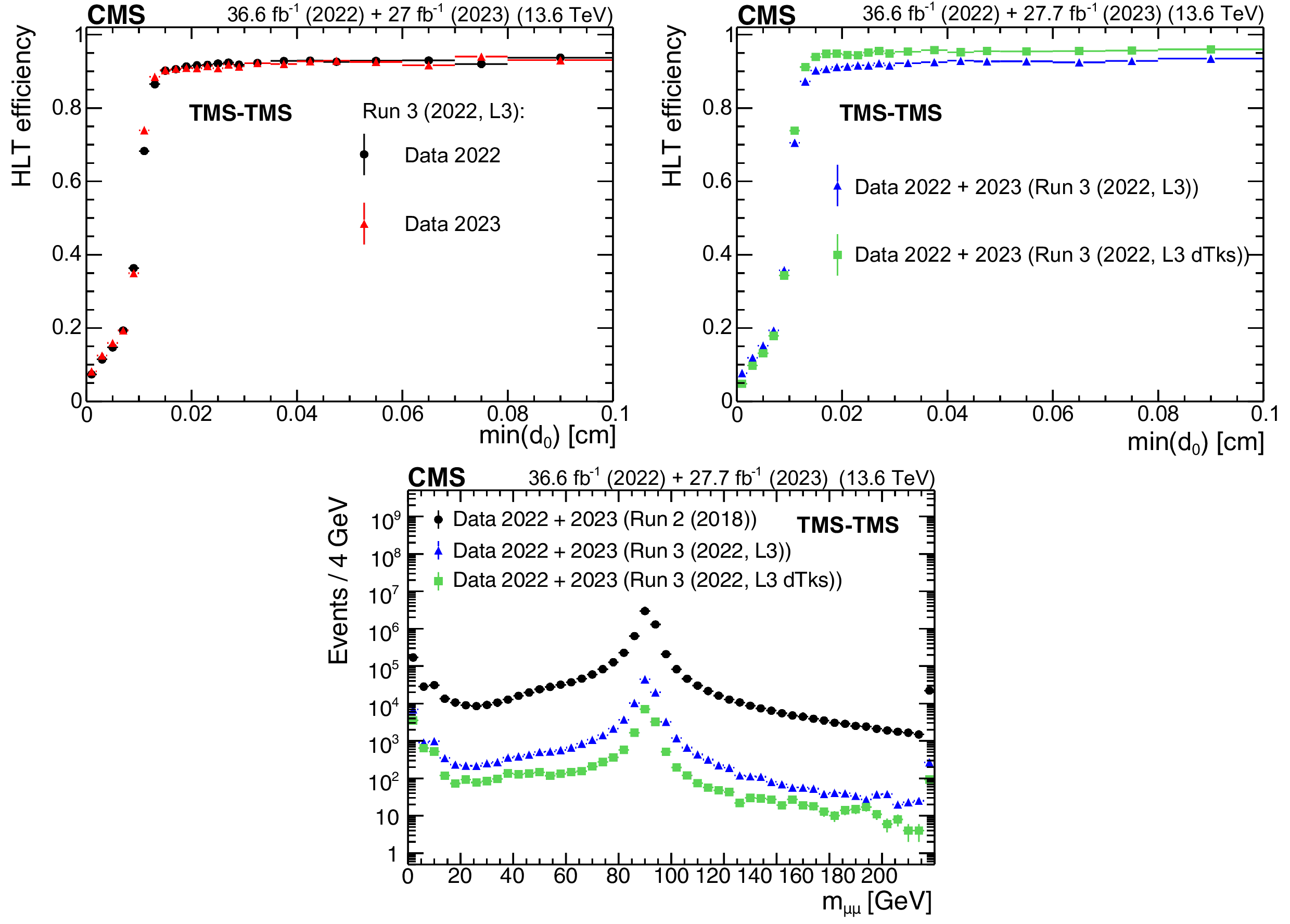

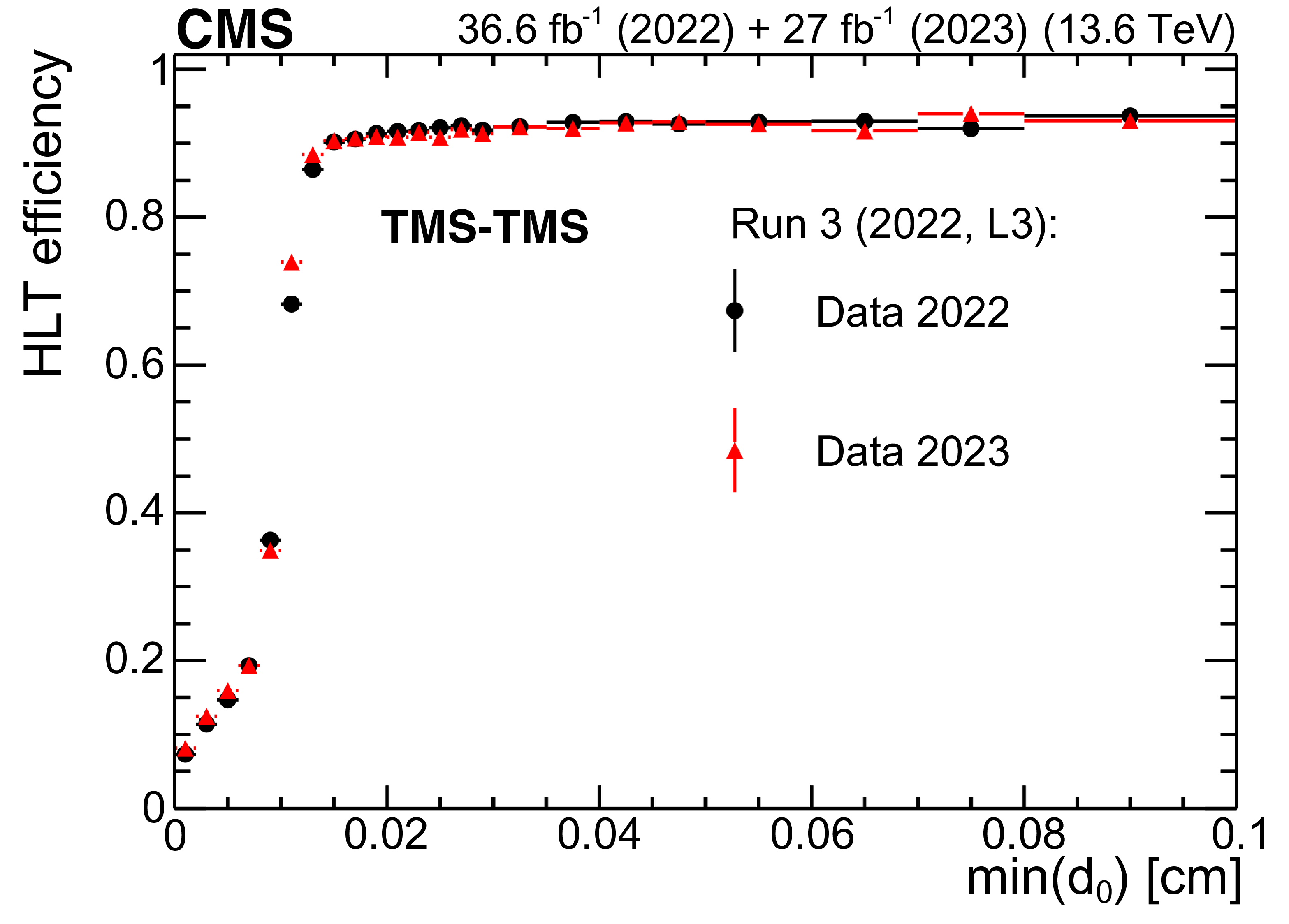

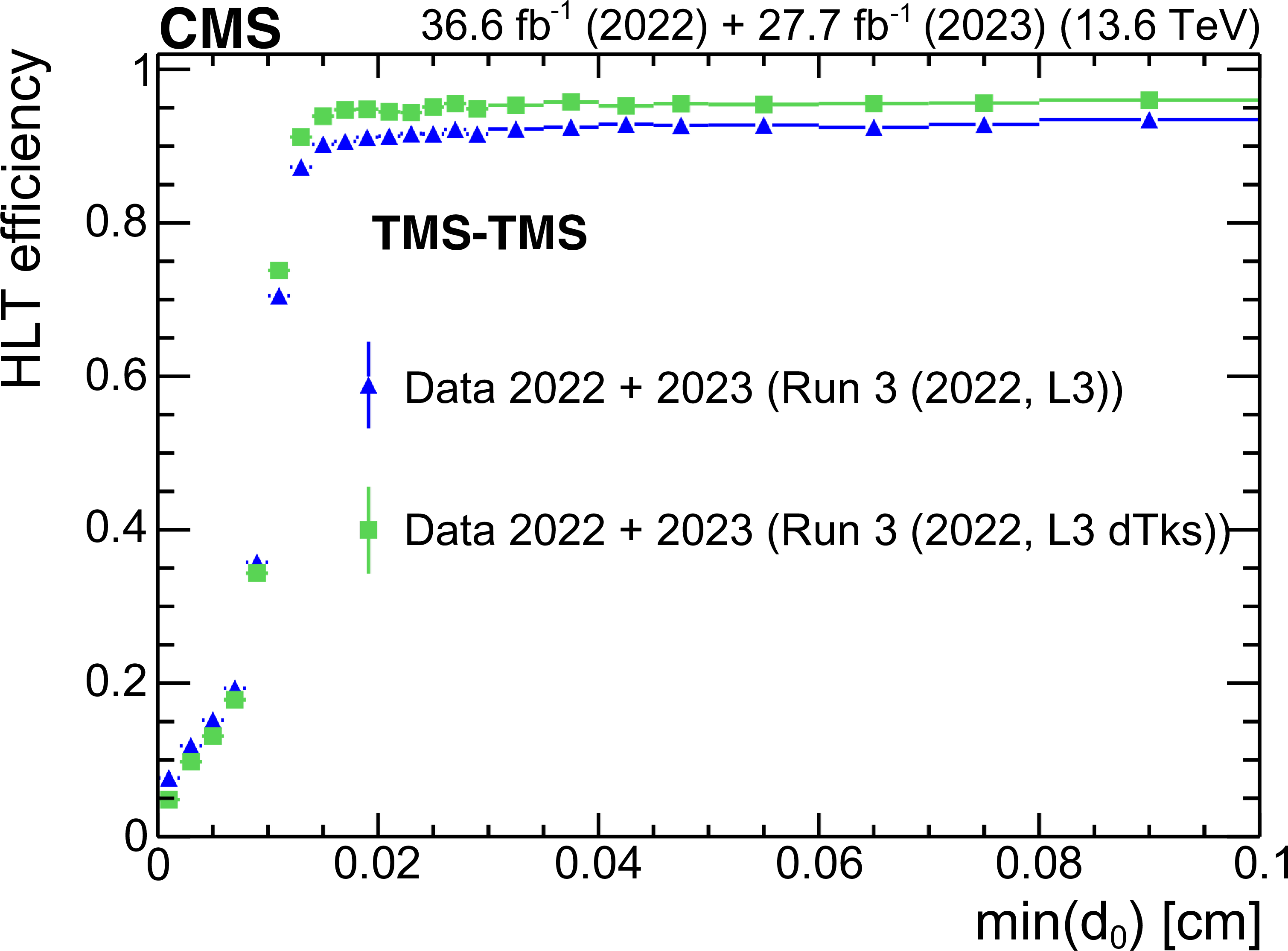

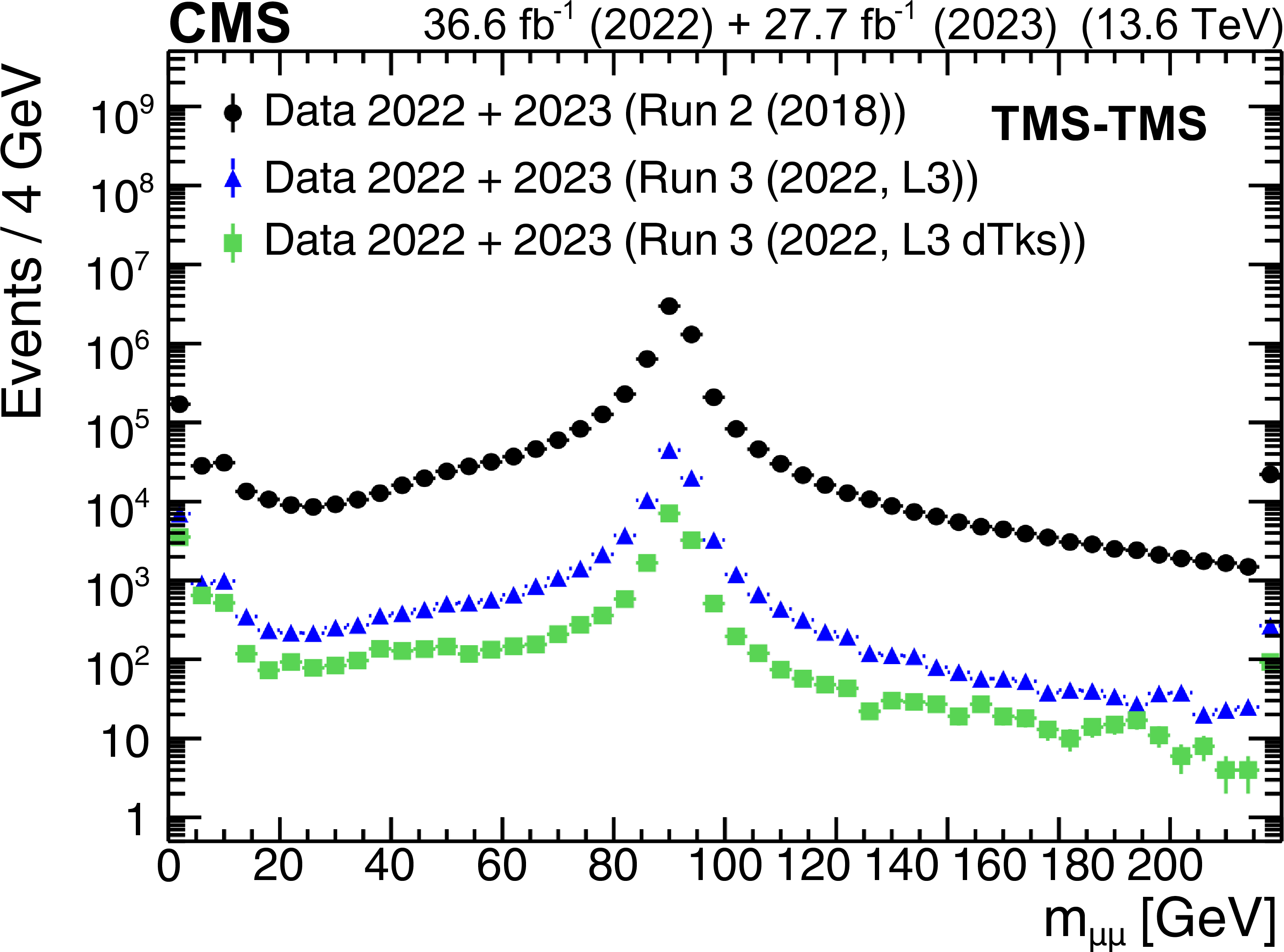

The HLT efficiency (upper left), defined as the fraction of events recorded by the Run 2 (2018) triggers that also satisfy the requirements of the Run 3 (2022, L3) triggers, as a function of offline-reconstructed $ \text{min}(d_{\text{0}}) $ of the two muons forming TMS-TMS dimuons in events enriched in $ \mathrm{J}/\psi\to\mu\mu $, for the 2022 and 2023 data-taking periods. The black circles represent efficiencies during the 2022 data-taking period, and the red triangles represent the 2023 period. For dimuons with offline $ \text{min}(d_{\text{0}}) > 0.012 \text{cm} $, the combined efficiency of the L3 muon reconstruction and the online $ \text{min}(d_{\text{0}}) $ requirement is larger than 90% in all data-taking periods. The HLT efficiency of the Run 3 (2022, L3) triggers (upper right), shown with blue triangles, and the Run 3 (2022, L3 dTks) triggers, shown with green squares, for $ \mathrm{J}/\psi\to\mu\mu $ events in the 2022 and 2023 data sets. Invariant mass distribution for TMS-TMS dimuons (lower) in events recorded by the Run 2 (2018) triggers in the combined 2022 and 2023 data set (black circles), and in the subset of events also selected by the Run 3 (2022, L3) trigger (blue triangles) and Run 3 (2022, L3 dTks) trigger (green squares), illustrating the prompt muon rejection of the L3 triggers. |

png pdf |

Figure 43-a:

The HLT efficiency (upper left), defined as the fraction of events recorded by the Run 2 (2018) triggers that also satisfy the requirements of the Run 3 (2022, L3) triggers, as a function of offline-reconstructed $ \text{min}(d_{\text{0}}) $ of the two muons forming TMS-TMS dimuons in events enriched in $ \mathrm{J}/\psi\to\mu\mu $, for the 2022 and 2023 data-taking periods. The black circles represent efficiencies during the 2022 data-taking period, and the red triangles represent the 2023 period. For dimuons with offline $ \text{min}(d_{\text{0}}) > 0.012 \text{cm} $, the combined efficiency of the L3 muon reconstruction and the online $ \text{min}(d_{\text{0}}) $ requirement is larger than 90% in all data-taking periods. The HLT efficiency of the Run 3 (2022, L3) triggers (upper right), shown with blue triangles, and the Run 3 (2022, L3 dTks) triggers, shown with green squares, for $ \mathrm{J}/\psi\to\mu\mu $ events in the 2022 and 2023 data sets. Invariant mass distribution for TMS-TMS dimuons (lower) in events recorded by the Run 2 (2018) triggers in the combined 2022 and 2023 data set (black circles), and in the subset of events also selected by the Run 3 (2022, L3) trigger (blue triangles) and Run 3 (2022, L3 dTks) trigger (green squares), illustrating the prompt muon rejection of the L3 triggers. |

png pdf |

Figure 43-b:

The HLT efficiency (upper left), defined as the fraction of events recorded by the Run 2 (2018) triggers that also satisfy the requirements of the Run 3 (2022, L3) triggers, as a function of offline-reconstructed $ \text{min}(d_{\text{0}}) $ of the two muons forming TMS-TMS dimuons in events enriched in $ \mathrm{J}/\psi\to\mu\mu $, for the 2022 and 2023 data-taking periods. The black circles represent efficiencies during the 2022 data-taking period, and the red triangles represent the 2023 period. For dimuons with offline $ \text{min}(d_{\text{0}}) > 0.012 \text{cm} $, the combined efficiency of the L3 muon reconstruction and the online $ \text{min}(d_{\text{0}}) $ requirement is larger than 90% in all data-taking periods. The HLT efficiency of the Run 3 (2022, L3) triggers (upper right), shown with blue triangles, and the Run 3 (2022, L3 dTks) triggers, shown with green squares, for $ \mathrm{J}/\psi\to\mu\mu $ events in the 2022 and 2023 data sets. Invariant mass distribution for TMS-TMS dimuons (lower) in events recorded by the Run 2 (2018) triggers in the combined 2022 and 2023 data set (black circles), and in the subset of events also selected by the Run 3 (2022, L3) trigger (blue triangles) and Run 3 (2022, L3 dTks) trigger (green squares), illustrating the prompt muon rejection of the L3 triggers. |

png pdf |

Figure 43-c:

The HLT efficiency (upper left), defined as the fraction of events recorded by the Run 2 (2018) triggers that also satisfy the requirements of the Run 3 (2022, L3) triggers, as a function of offline-reconstructed $ \text{min}(d_{\text{0}}) $ of the two muons forming TMS-TMS dimuons in events enriched in $ \mathrm{J}/\psi\to\mu\mu $, for the 2022 and 2023 data-taking periods. The black circles represent efficiencies during the 2022 data-taking period, and the red triangles represent the 2023 period. For dimuons with offline $ \text{min}(d_{\text{0}}) > 0.012 \text{cm} $, the combined efficiency of the L3 muon reconstruction and the online $ \text{min}(d_{\text{0}}) $ requirement is larger than 90% in all data-taking periods. The HLT efficiency of the Run 3 (2022, L3) triggers (upper right), shown with blue triangles, and the Run 3 (2022, L3 dTks) triggers, shown with green squares, for $ \mathrm{J}/\psi\to\mu\mu $ events in the 2022 and 2023 data sets. Invariant mass distribution for TMS-TMS dimuons (lower) in events recorded by the Run 2 (2018) triggers in the combined 2022 and 2023 data set (black circles), and in the subset of events also selected by the Run 3 (2022, L3) trigger (blue triangles) and Run 3 (2022, L3 dTks) trigger (green squares), illustrating the prompt muon rejection of the L3 triggers. |

png pdf |

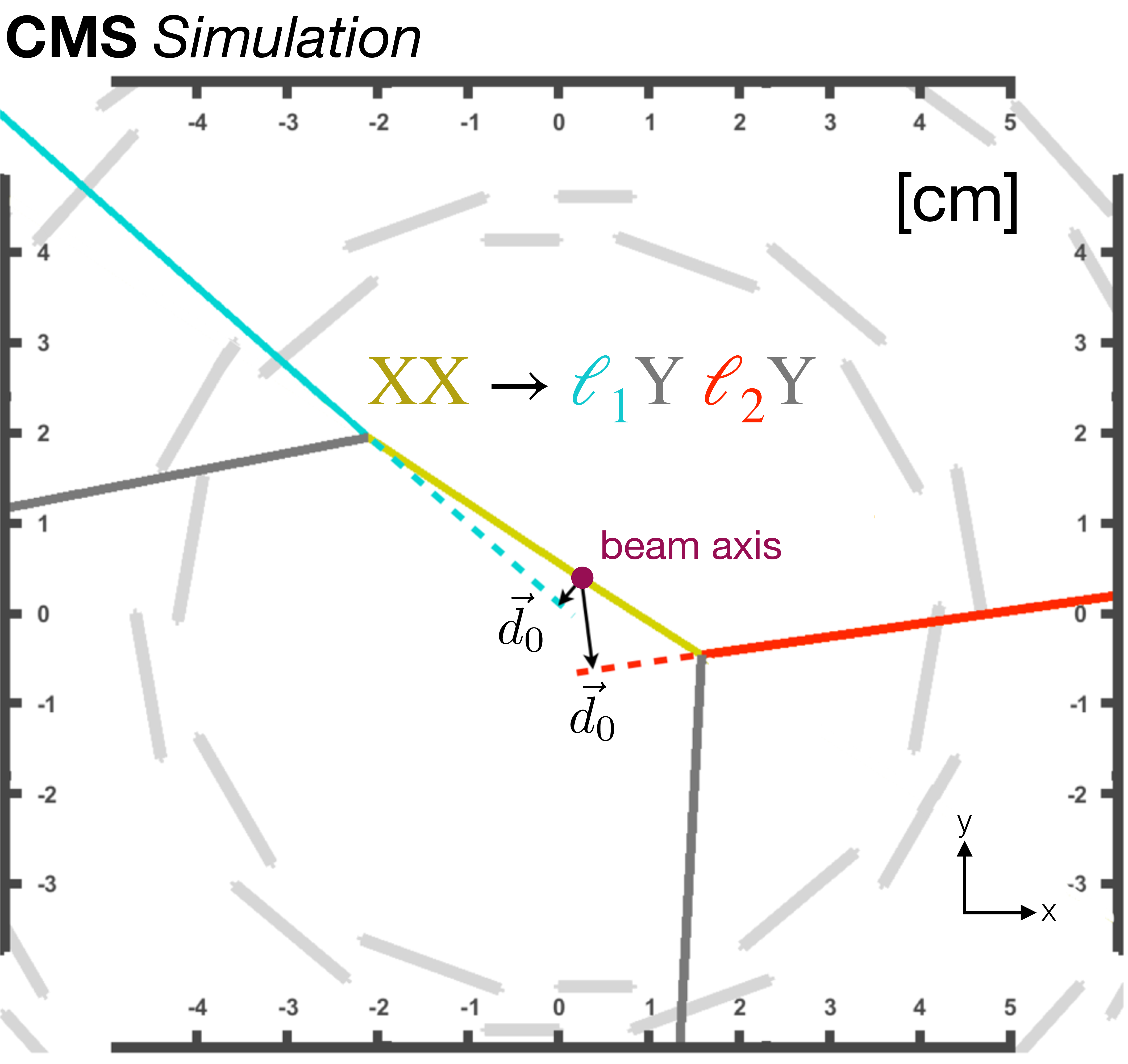

Figure 44:

Diagram of a simulated signal event in the inclusive displaced-lepton search [127], from a transverse view of the IP. The cyan and red solid lines indicate the trajectories of the two leptons, and the two dashed lines indicate the extrapolation of the trajectories towards their point of closest approach to the beam axis. The black arrows, which point from the beam axis and are orthogonal to the cyan and red dotted lines, indicate the lepton $ d_{\text{0}} $ vectors. Figure adapted from Ref. [131]. |

png pdf |

Figure 45:

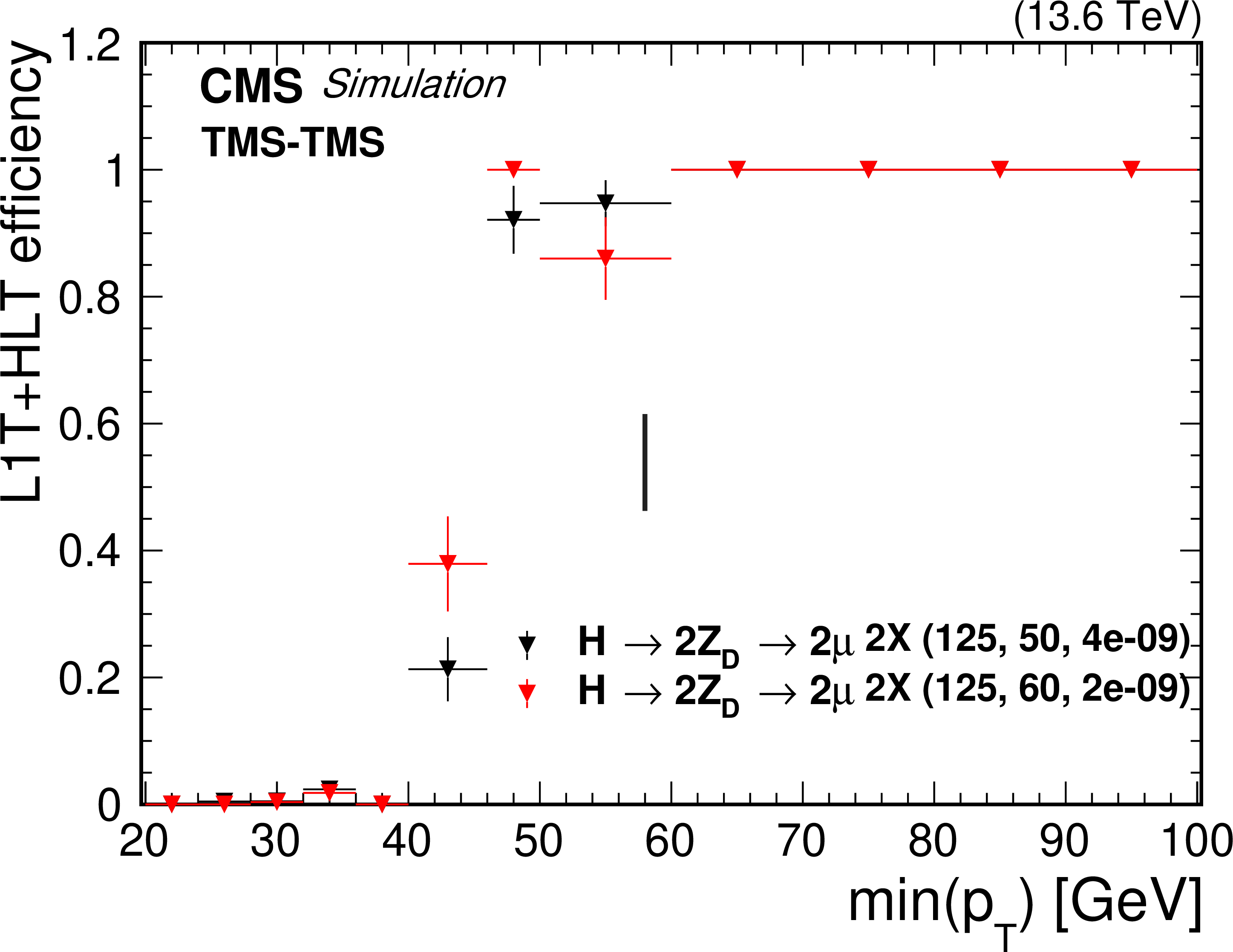

The L1T+HLT efficiency of the double displaced L3 muon trigger as a function of $ \text{min}(p_{\mathrm{T}}) $ of the two global or tracker muons in the event. The efficiency is plotted for HAHM signal events for 2022 conditions with $ m_{\mathrm{Z}_\text{D}} = $ 50 GeV and $ \epsilon = 4 \times 10^{-9} $ (black triangles), $ m_{\mathrm{Z}_\text{D}} = $ 60 GeV and $ \epsilon = 2 \times 10^{-9} $ (red triangles), and $ m_{\mathrm{H}}= $ 125 GeV in both cases. The events are required to have at least two good global or tracker muons with $ p_{\mathrm{T}} > $ 23 GeV. |

png pdf |

Figure 46:

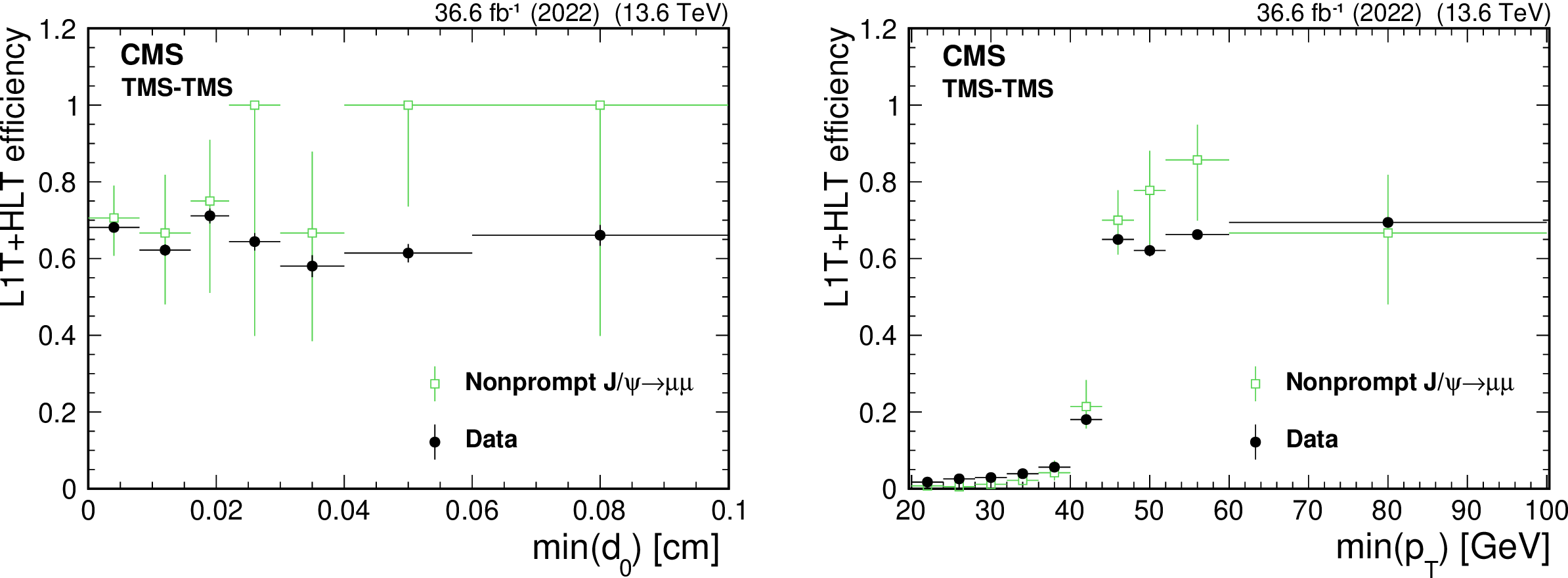

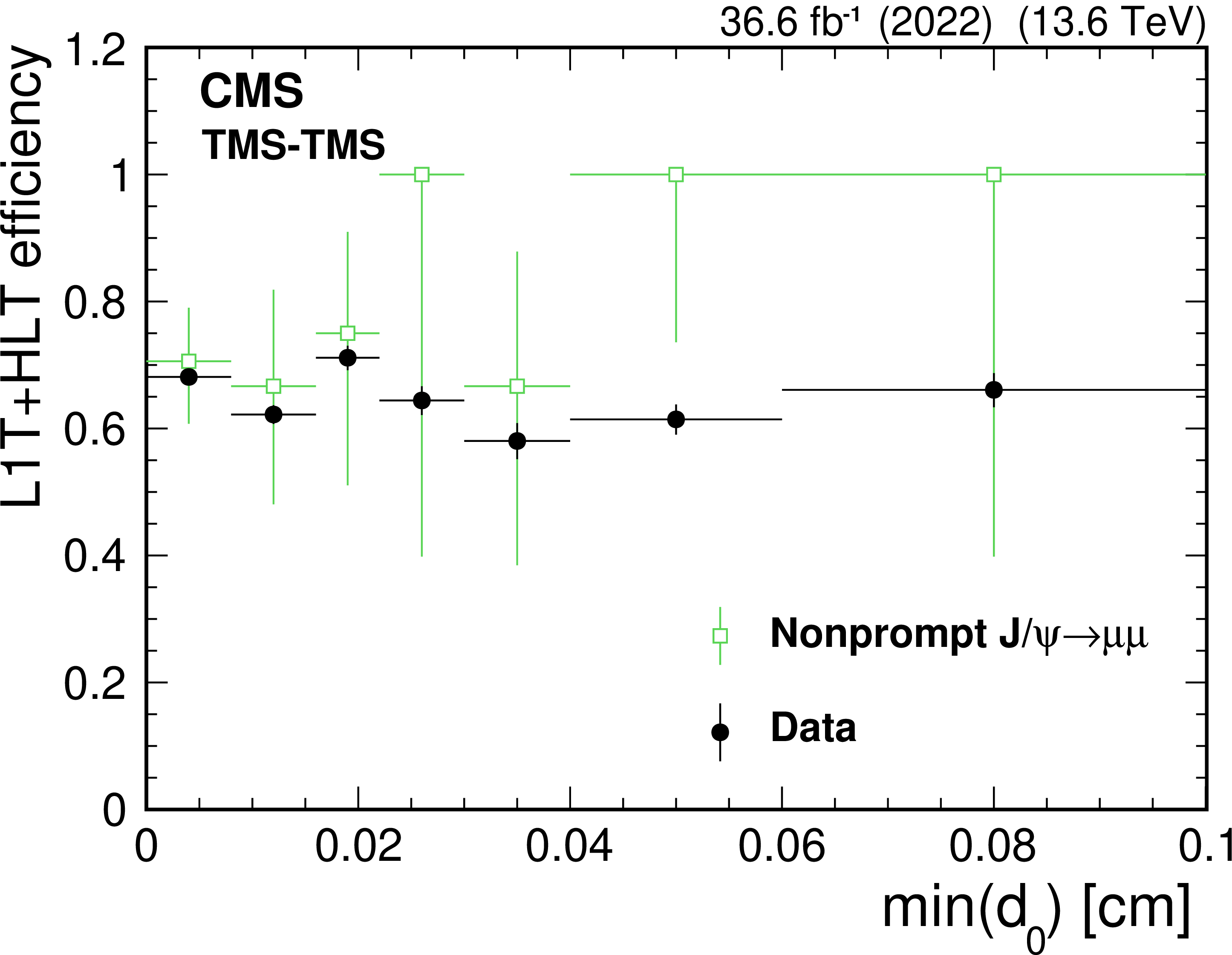

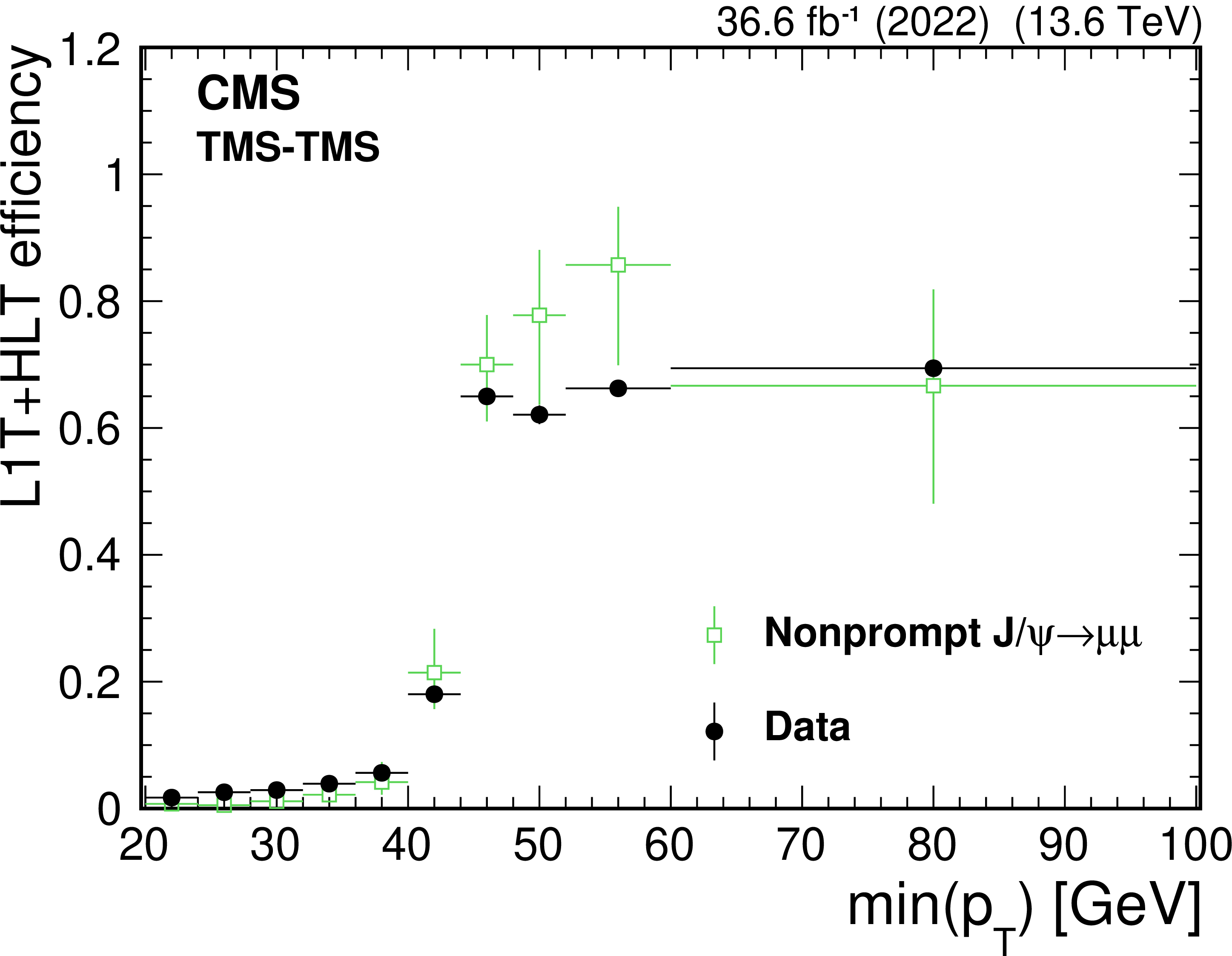

The L1T+HLT efficiency of the double displaced L3 muon trigger in 2022, as a function of $ \text{min}(d_{\text{0}}) $ (left) and $ \text{min}(p_{\mathrm{T}}) $ (right) of the two global or tracker muons in the event. The efficiency is plotted for simulated $ \mathrm{J}/\psi\to\mu\mu $ events produced in various b hadron decays (open green squares) and data enriched in $ \mathrm{J}/\psi\to\mu\mu $ events recorded by jet- and $ p_{\mathrm{T}}^\text{miss} $-based triggers (filled black circles). The events are required to have at least two good global or tracker muons compatible with the $ \mathrm{J}/\psi $ meson mass and with $ p_{\mathrm{T}} > $ 45 GeV (left) or $ p_{\mathrm{T}} > $ 23 GeV (right). |

png pdf |

Figure 46-a:

The L1T+HLT efficiency of the double displaced L3 muon trigger in 2022, as a function of $ \text{min}(d_{\text{0}}) $ (left) and $ \text{min}(p_{\mathrm{T}}) $ (right) of the two global or tracker muons in the event. The efficiency is plotted for simulated $ \mathrm{J}/\psi\to\mu\mu $ events produced in various b hadron decays (open green squares) and data enriched in $ \mathrm{J}/\psi\to\mu\mu $ events recorded by jet- and $ p_{\mathrm{T}}^\text{miss} $-based triggers (filled black circles). The events are required to have at least two good global or tracker muons compatible with the $ \mathrm{J}/\psi $ meson mass and with $ p_{\mathrm{T}} > $ 45 GeV (left) or $ p_{\mathrm{T}} > $ 23 GeV (right). |

png pdf |

Figure 46-b:

The L1T+HLT efficiency of the double displaced L3 muon trigger in 2022, as a function of $ \text{min}(d_{\text{0}}) $ (left) and $ \text{min}(p_{\mathrm{T}}) $ (right) of the two global or tracker muons in the event. The efficiency is plotted for simulated $ \mathrm{J}/\psi\to\mu\mu $ events produced in various b hadron decays (open green squares) and data enriched in $ \mathrm{J}/\psi\to\mu\mu $ events recorded by jet- and $ p_{\mathrm{T}}^\text{miss} $-based triggers (filled black circles). The events are required to have at least two good global or tracker muons compatible with the $ \mathrm{J}/\psi $ meson mass and with $ p_{\mathrm{T}} > $ 45 GeV (left) or $ p_{\mathrm{T}} > $ 23 GeV (right). |

png pdf |

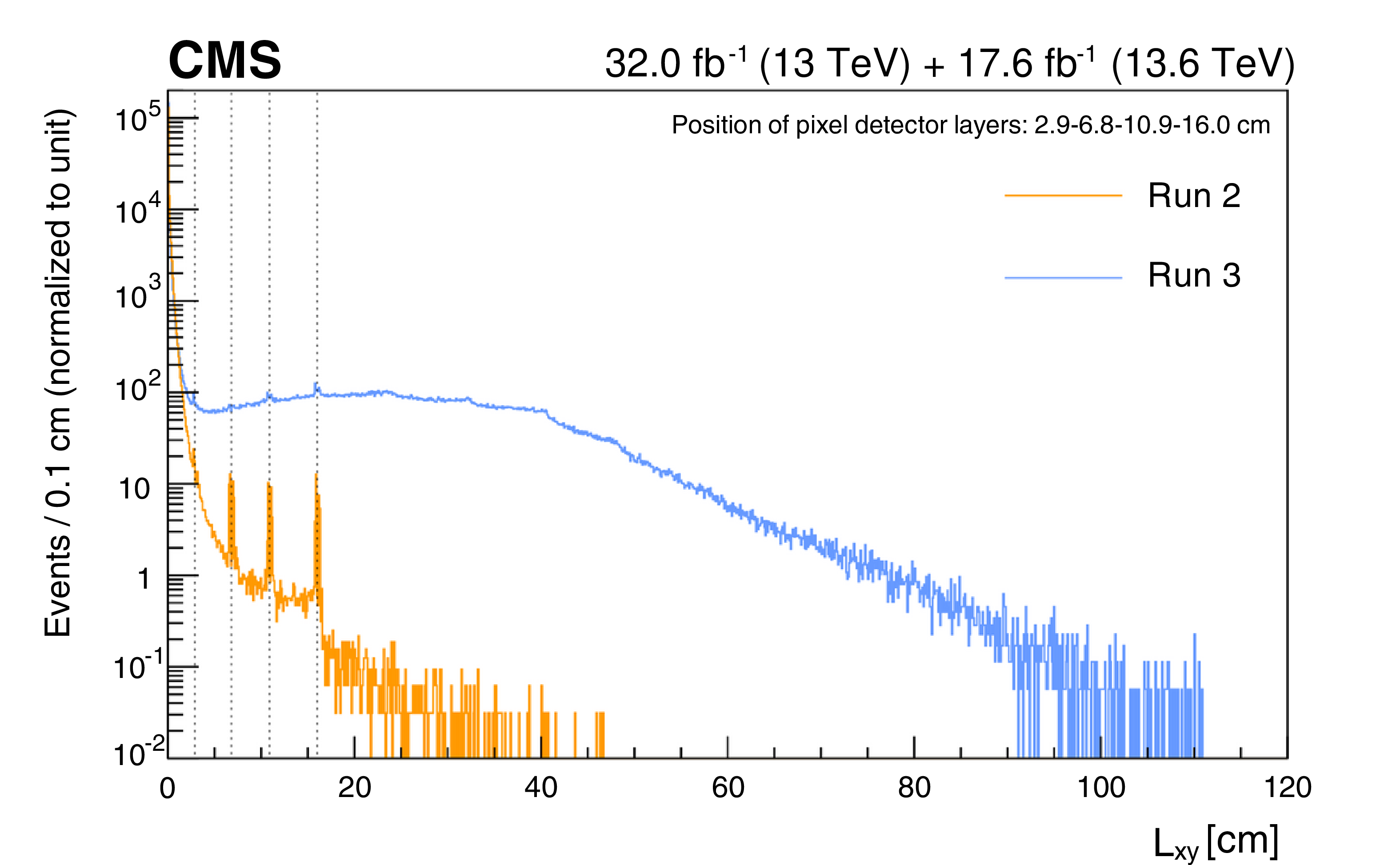

Figure 47:

Comparison between the $ L_{\text{xy}} $ distribution for dimuon scouting events for Run 2 (orange) and Run 3 (blue) events in data that contain dimuon pairs with a common displaced vertex and a minimal selection on the vertex quality. The blue Run 3 line is obtained from the vertex-unconstrained muon reconstruction algorithm. The dashed vertical lines, at radii of 2.9, 6.8, 10.9, and 16.0$ \text{cm} $, correspond to the positions of the pixel detector layers where photons undergo conversion processes in the material, causing the observed peaks in the $ L_{\text{xy}} $ distribution. Figure taken from Ref. [45]. |

png pdf |

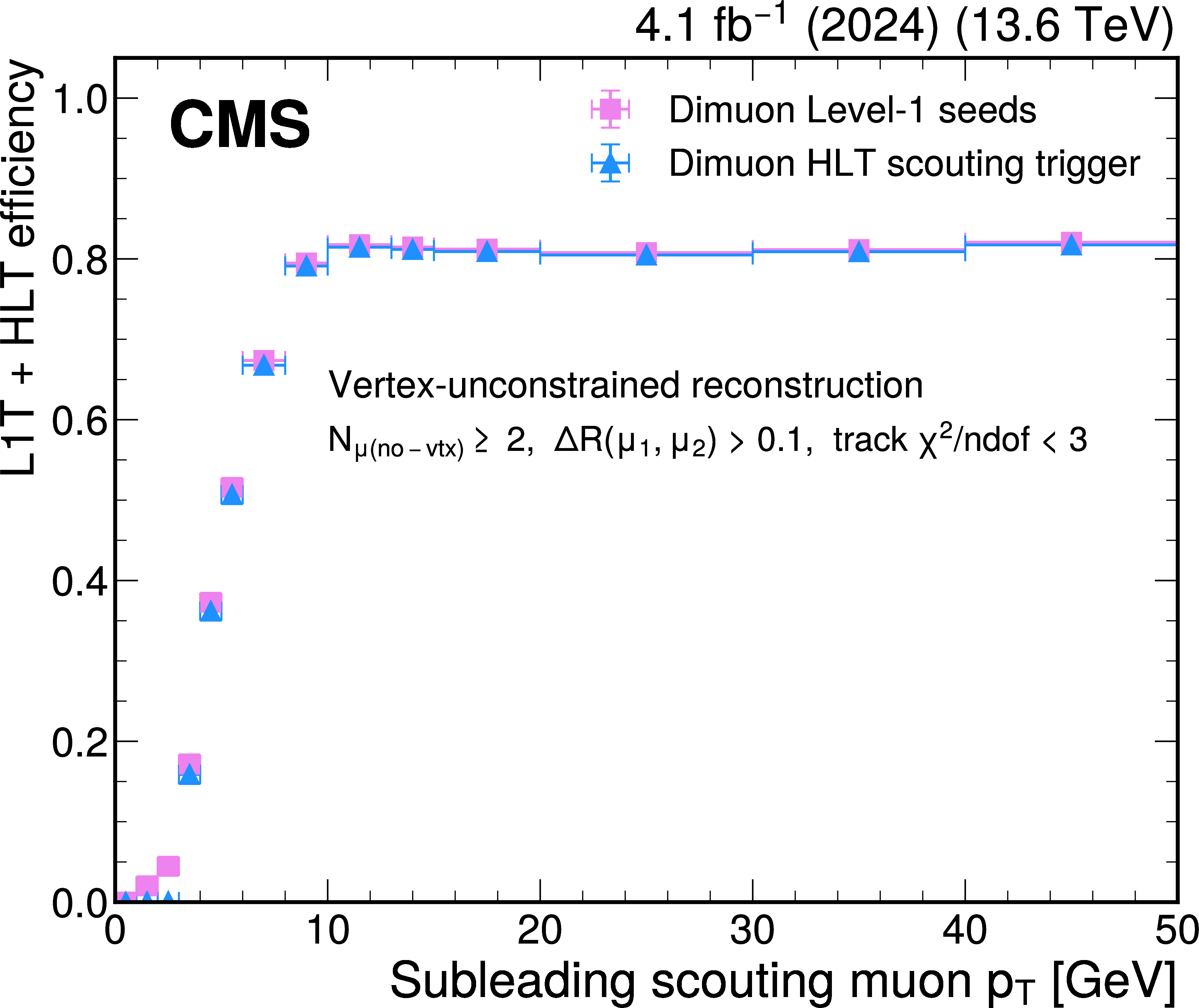

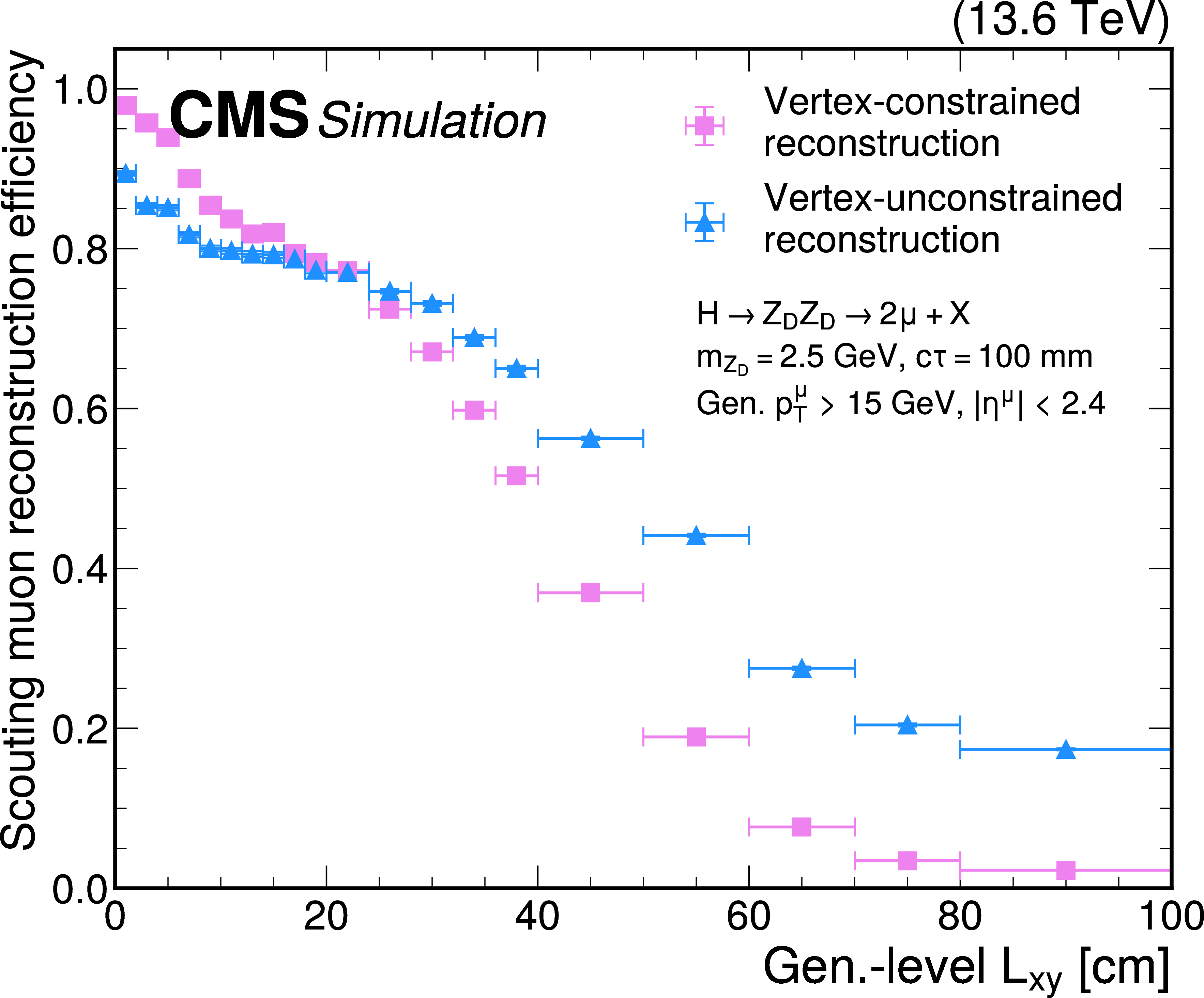

Figure 48:

The L1T+HLT efficiency of the dimuon scouting trigger as a function of the subleading muon $ p_{\mathrm{T}} $, for 2024 data. The efficiency of the L1T dimuon seeds (pink squares) and the HLT dimuon scouting trigger with the vertex-unconstrained reconstruction algorithm (blue triangles) is shown. The events in the denominator are required to have at least two vertex-unconstrained muons ($ N_{\mu $ (no-vtx) $ } > $ 2) and additionally to have $ \chi^2/N_{\text{dof}} < $ 3 and $ \Delta R > $ 0.1. |

png pdf |

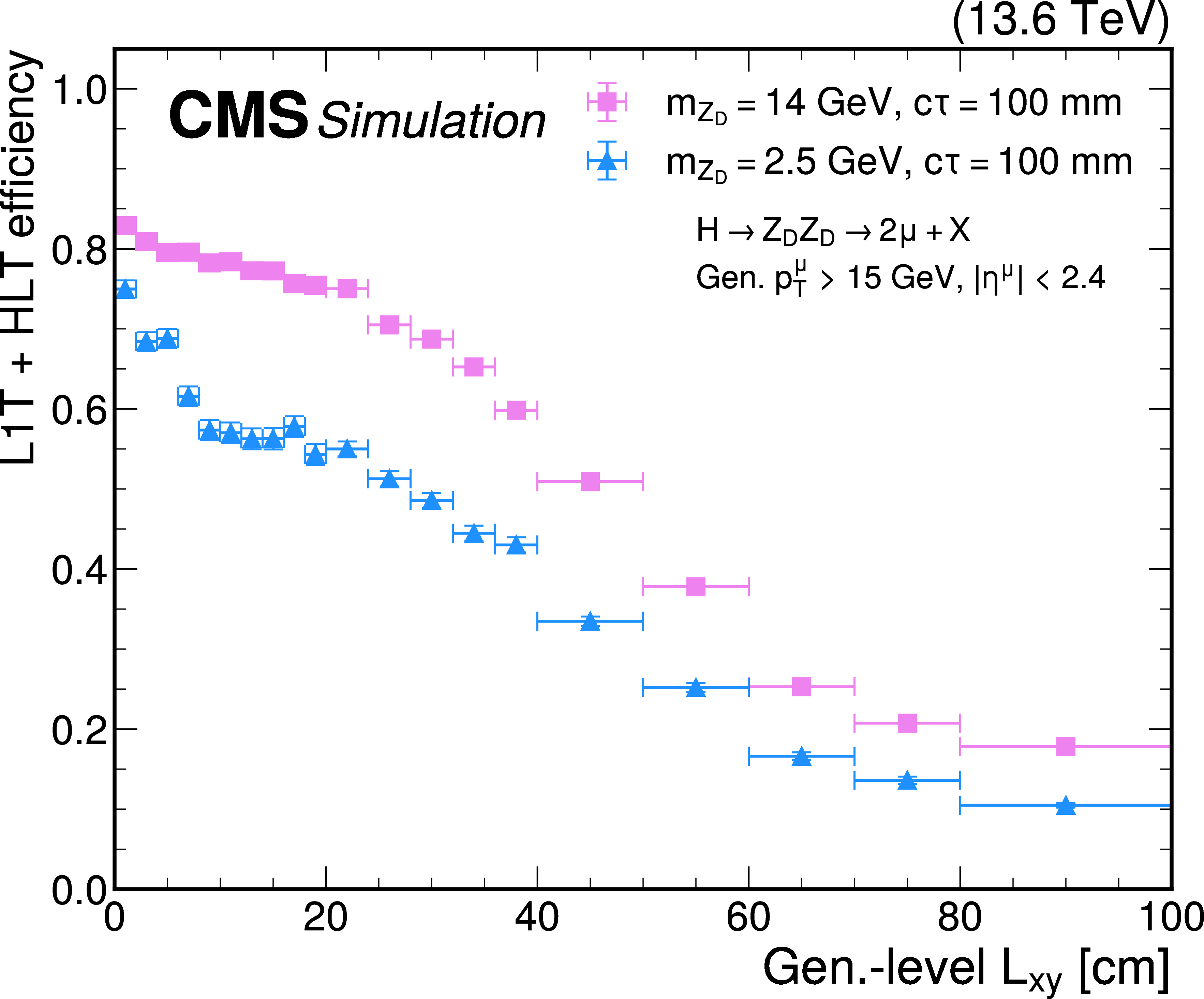

Figure 49:

The L1T+HLT efficiency of the dimuon scouting trigger as a function of the generator-level $ L_{\text{xy}} $, for HAHM signal events, for 2024 conditions. The efficiency is shown for $ m_{\mathrm{Z}_\text{D}} = $ 14 GeV and $ c\tau=100 \text{mm} $ (pink squares) and $ m_{\mathrm{Z}_\text{D}} = $ 2.5 GeV and $ c\tau=100 \text{mm} $ (blue triangles). The muons are required to have $ p_{\mathrm{T}} > $ 15 GeV and $ |\eta| < $ 2.4 at the generator level. |

png pdf |

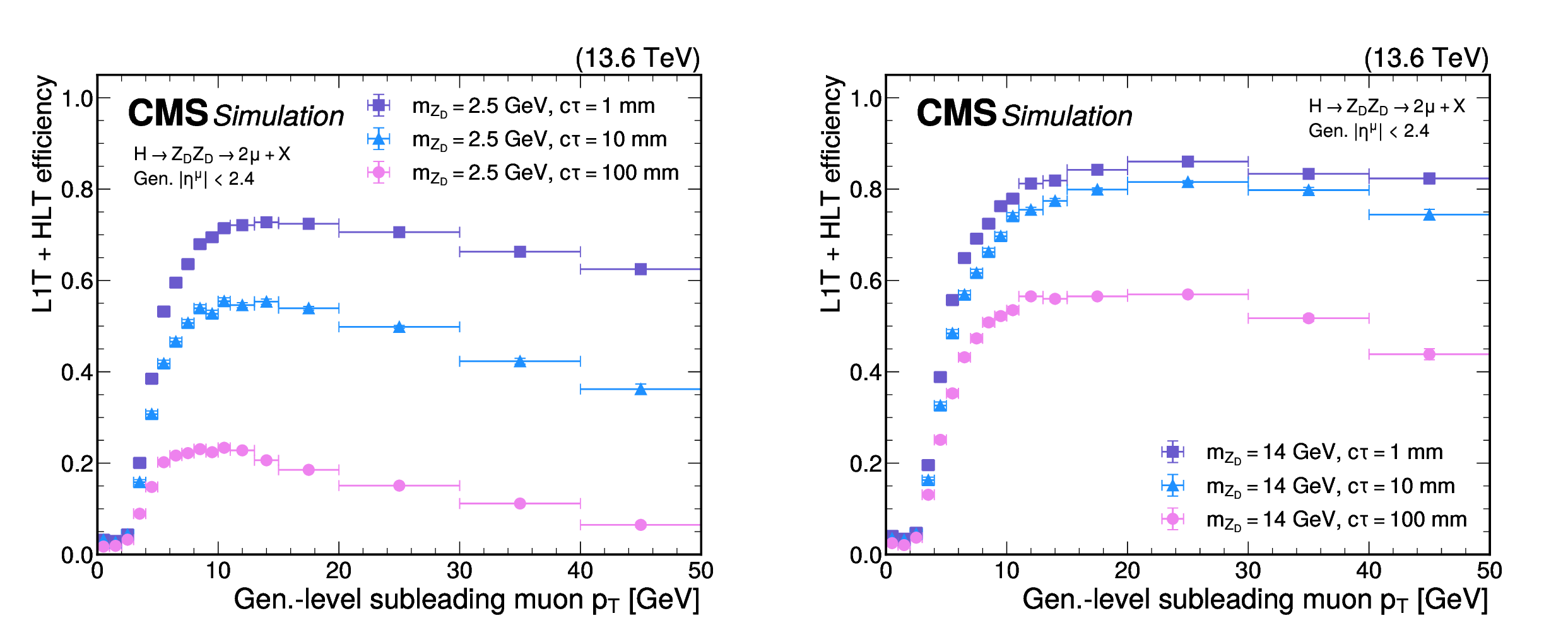

Figure 50:

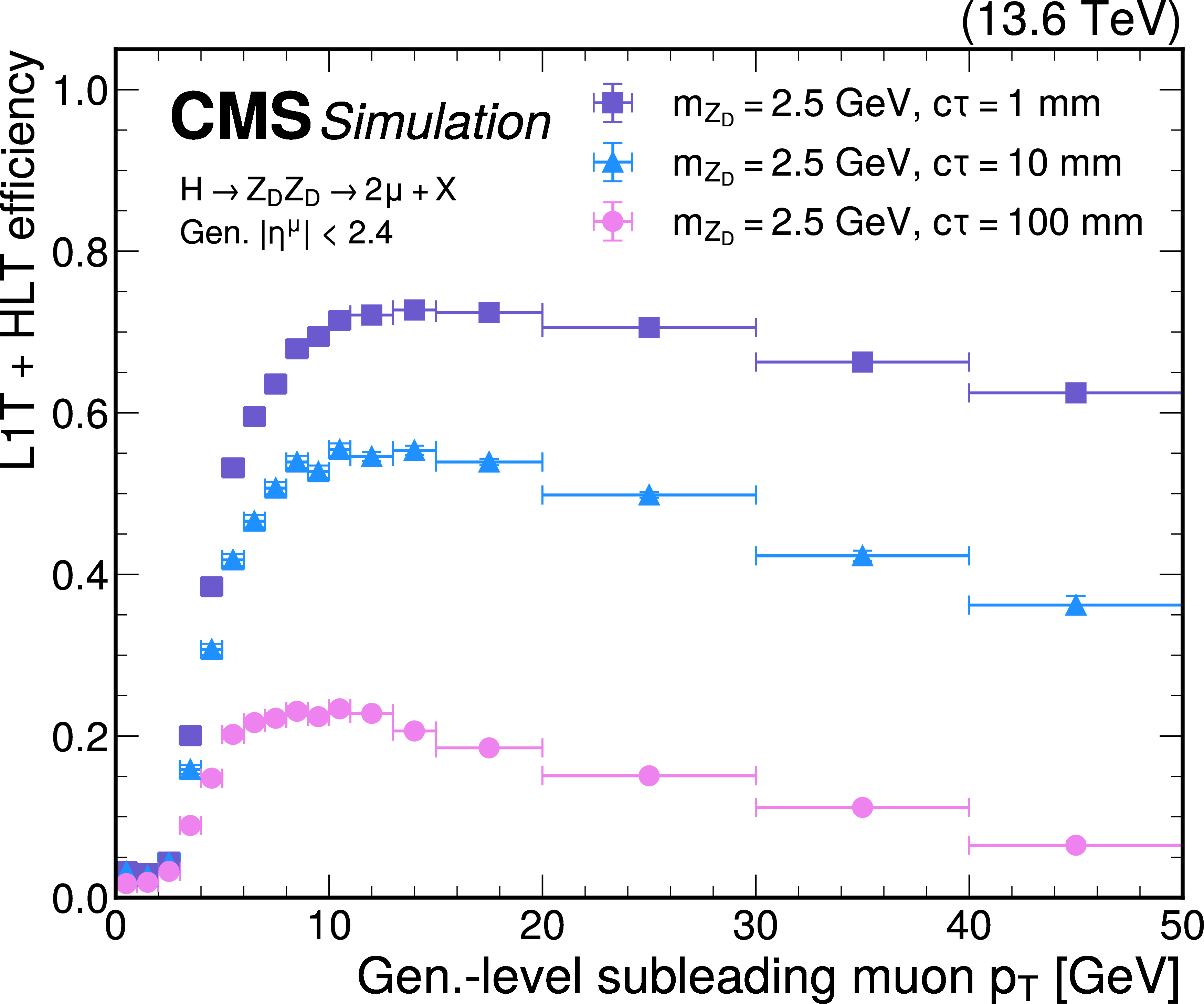

The L1T+HLT efficiency of the dimuon scouting trigger as a function of the generator-level subleading muon $ p_{\mathrm{T}} $, for HAHM signal events for 2024 conditions. The efficiency is shown for $ \mathrm{Z}_\text{D} $ masses of 2.5 (left) and 14 GeV (right), and $ c\tau $ values of 1 (purple squares), 10 (blue triangles), and 100$ \text{mm} $ (pink circles). The muons are required to have $ |\eta| < $ 2.4 at the generator level. |

png pdf |

Figure 50-a:

The L1T+HLT efficiency of the dimuon scouting trigger as a function of the generator-level subleading muon $ p_{\mathrm{T}} $, for HAHM signal events for 2024 conditions. The efficiency is shown for $ \mathrm{Z}_\text{D} $ masses of 2.5 (left) and 14 GeV (right), and $ c\tau $ values of 1 (purple squares), 10 (blue triangles), and 100$ \text{mm} $ (pink circles). The muons are required to have $ |\eta| < $ 2.4 at the generator level. |

png pdf |

Figure 50-b:

The L1T+HLT efficiency of the dimuon scouting trigger as a function of the generator-level subleading muon $ p_{\mathrm{T}} $, for HAHM signal events for 2024 conditions. The efficiency is shown for $ \mathrm{Z}_\text{D} $ masses of 2.5 (left) and 14 GeV (right), and $ c\tau $ values of 1 (purple squares), 10 (blue triangles), and 100$ \text{mm} $ (pink circles). The muons are required to have $ |\eta| < $ 2.4 at the generator level. |

png pdf |

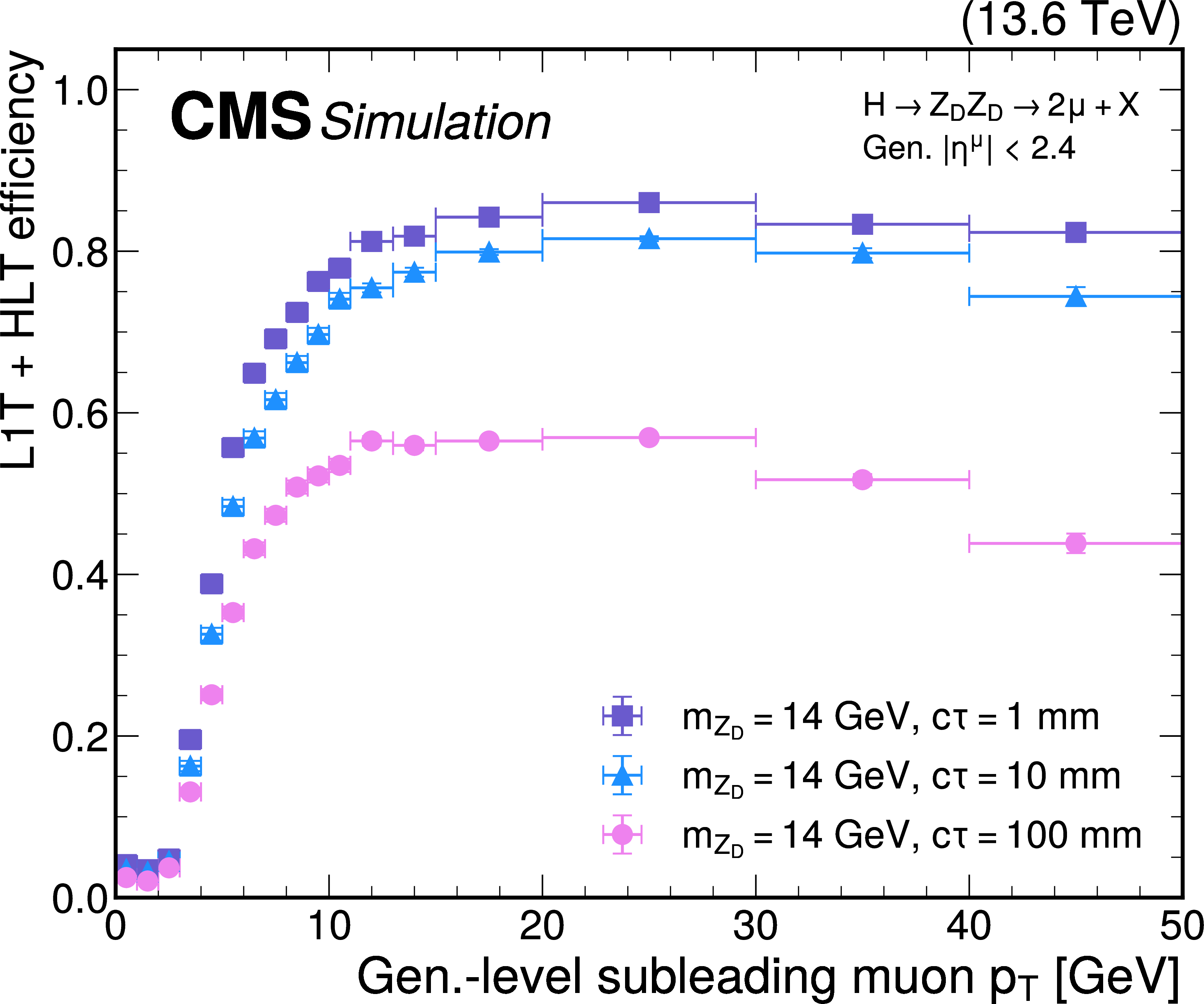

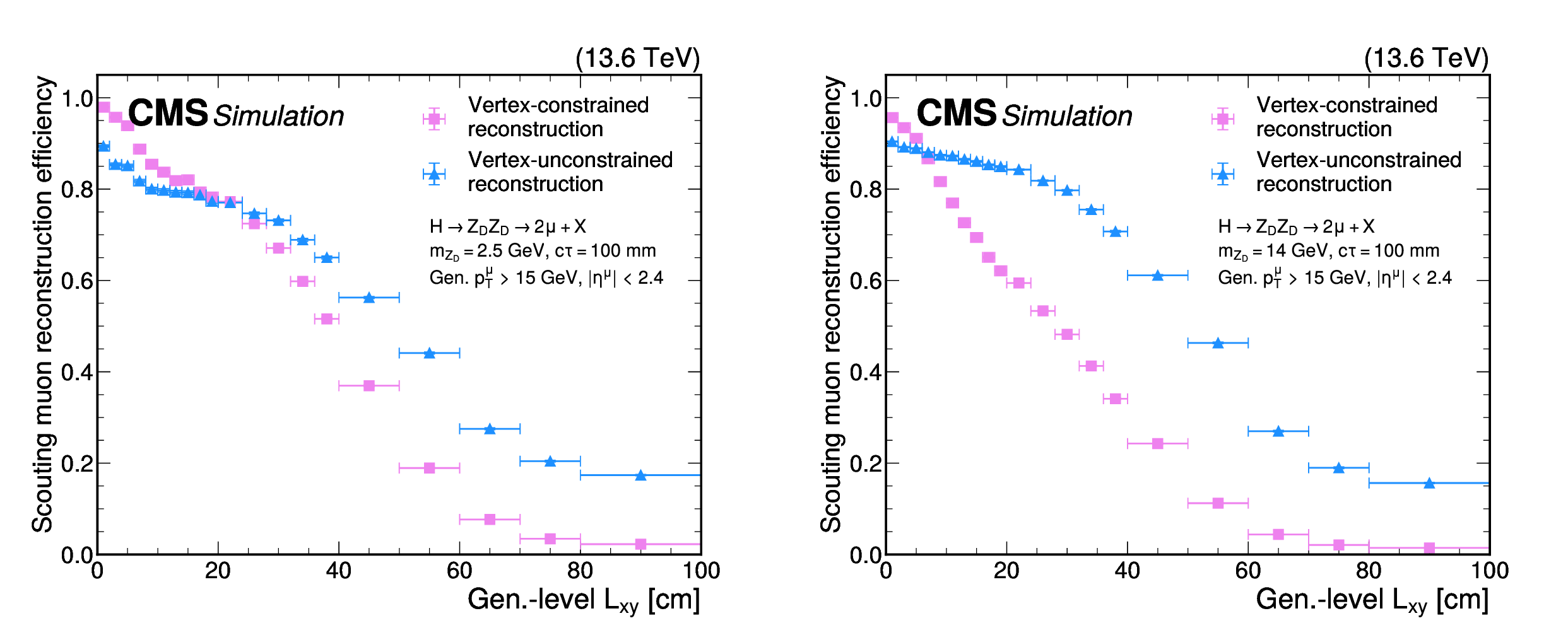

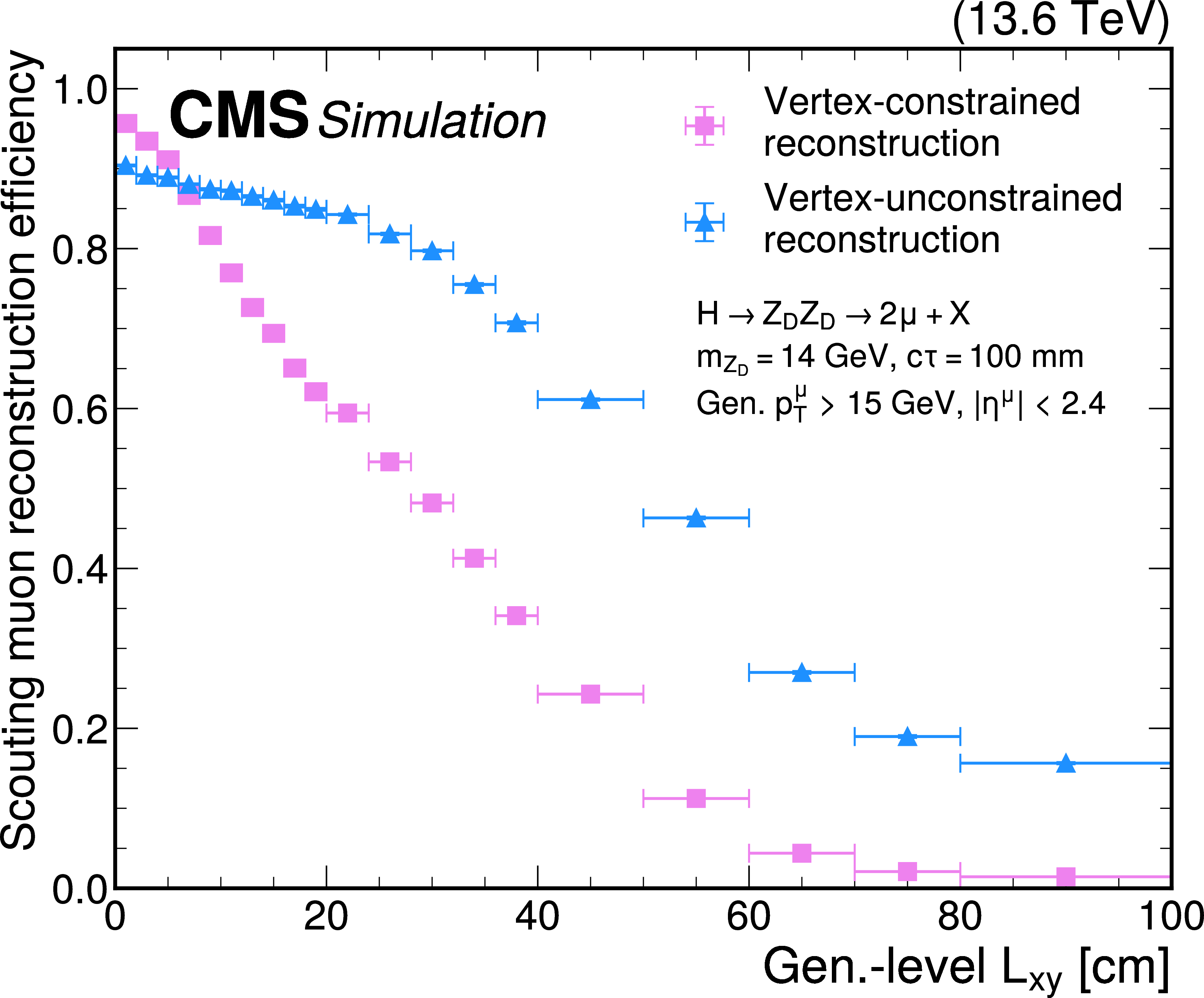

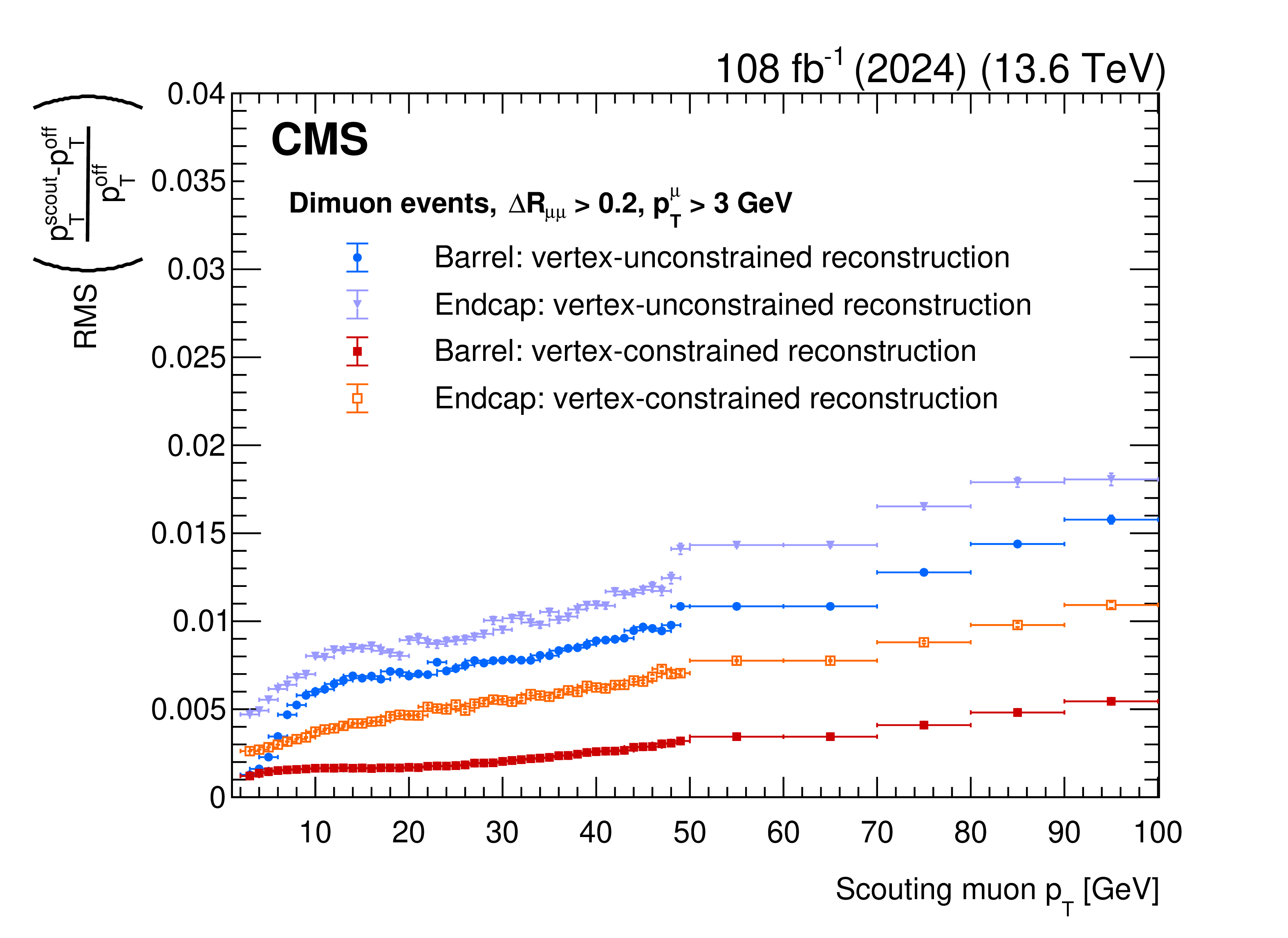

Figure 51:

Scouting muon reconstruction efficiency of the vertex-constrained (pink circles) and vertex-unconstrained (blue triangles) algorithms as a function of the generator-level $ L_{\text{xy}} $, for HAHM signal events for 2024 conditions. This efficiency is representative of the reconstruction efficiency of the L2 and L3 HLT muon reconstruction employed for scouting data. The efficiency is shown for $ m_{\mathrm{Z}_\text{D}} = $ 2.5 GeV and $ c\tau=100 \text{mm} $ (left) and $ m_{\mathrm{Z}_\text{D}} = $ 14 GeV and $ c\tau=100 \text{mm} $ (right). The muons are required to have $ p_{\mathrm{T}} > $ 15 GeV and $ |\eta| < $ 2.4 at the generator level. |

png pdf |

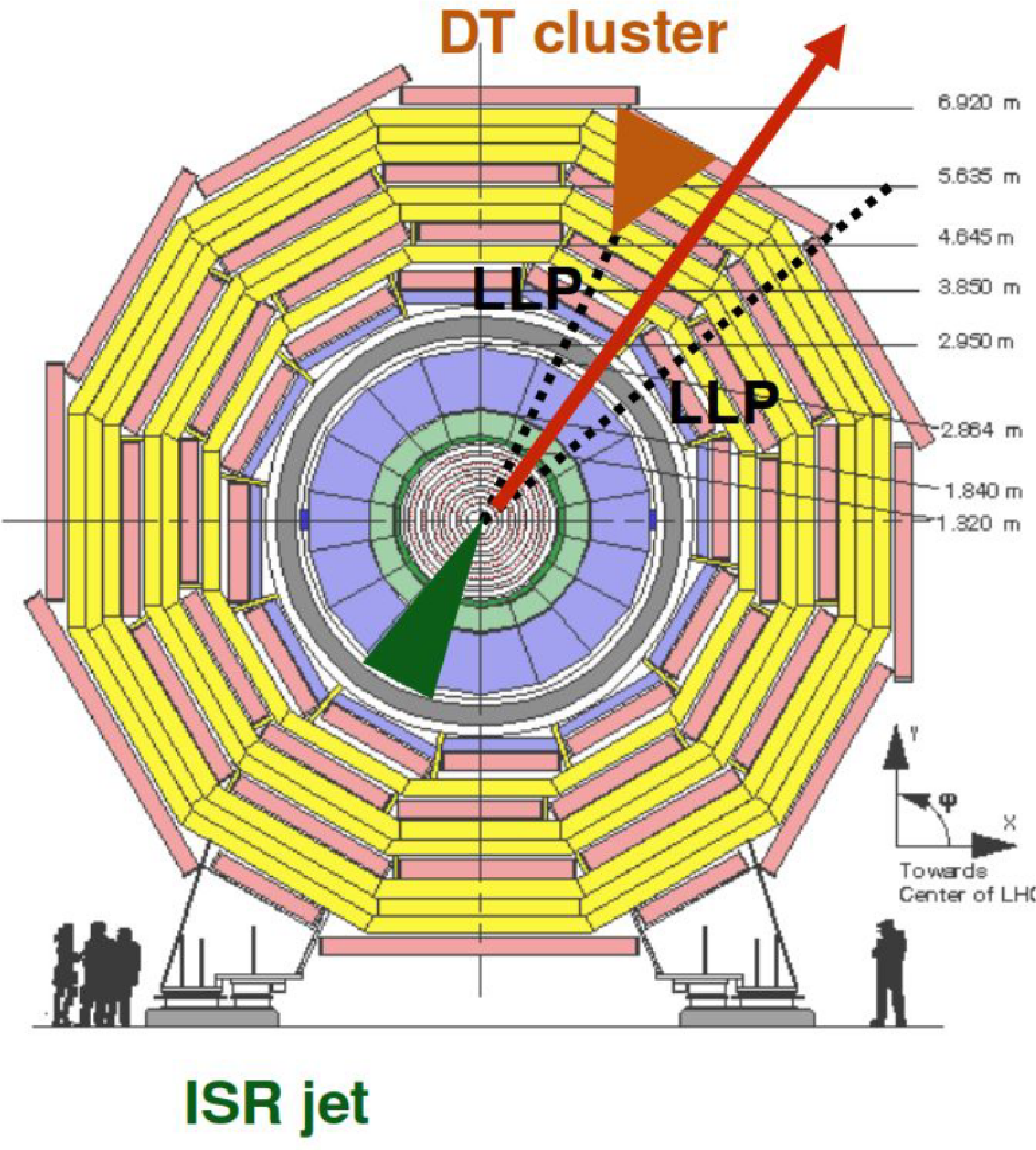

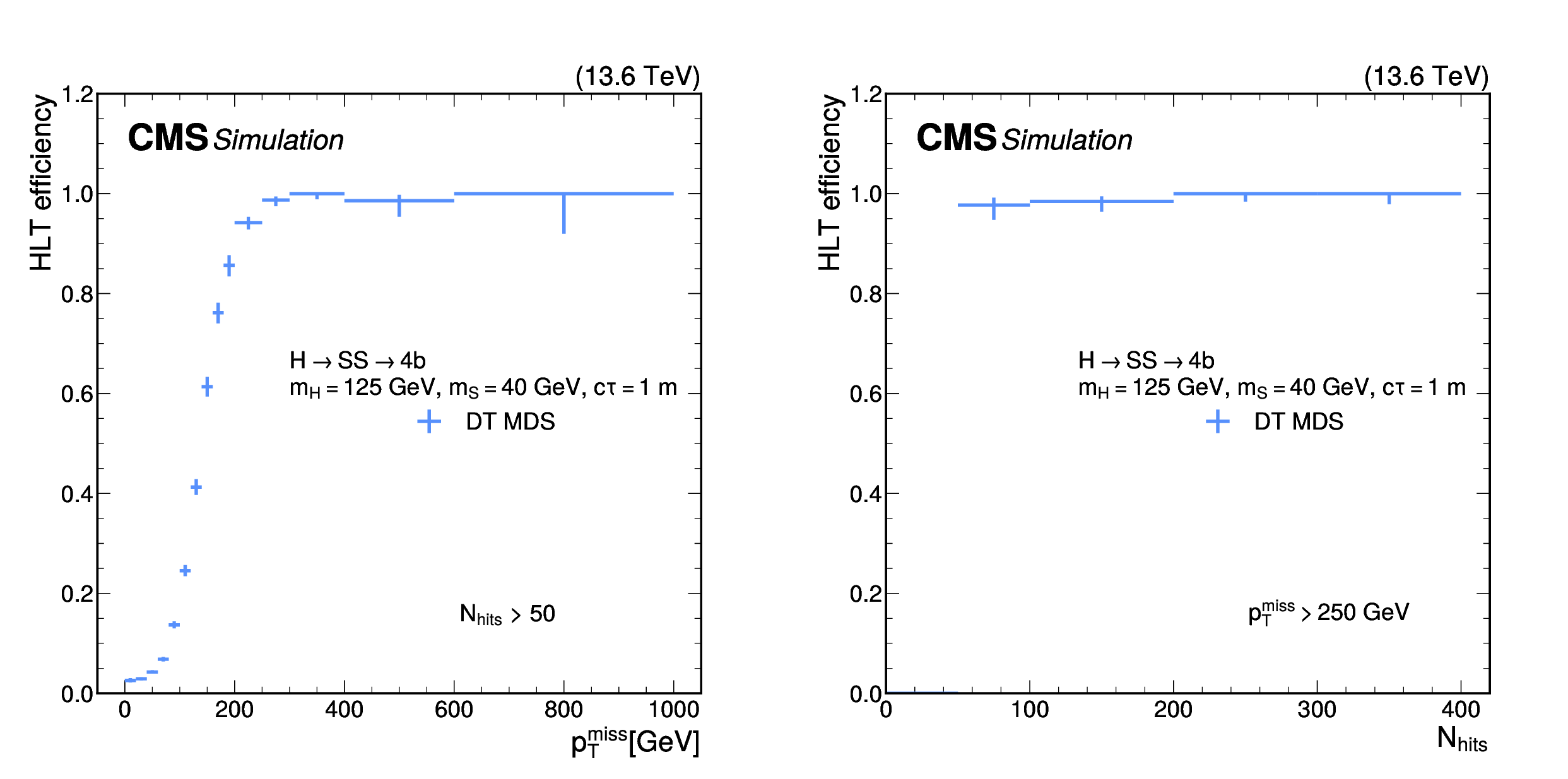

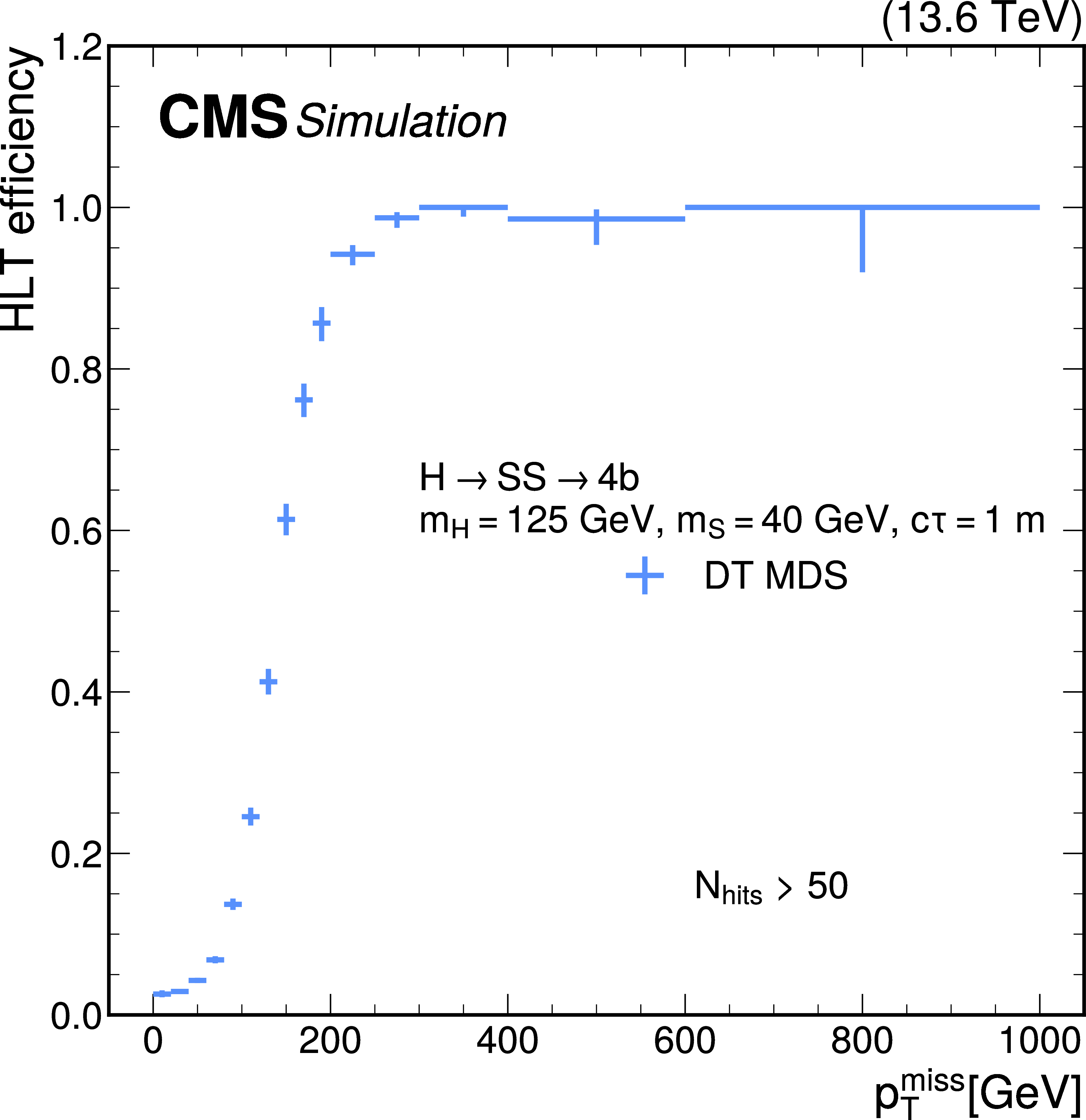

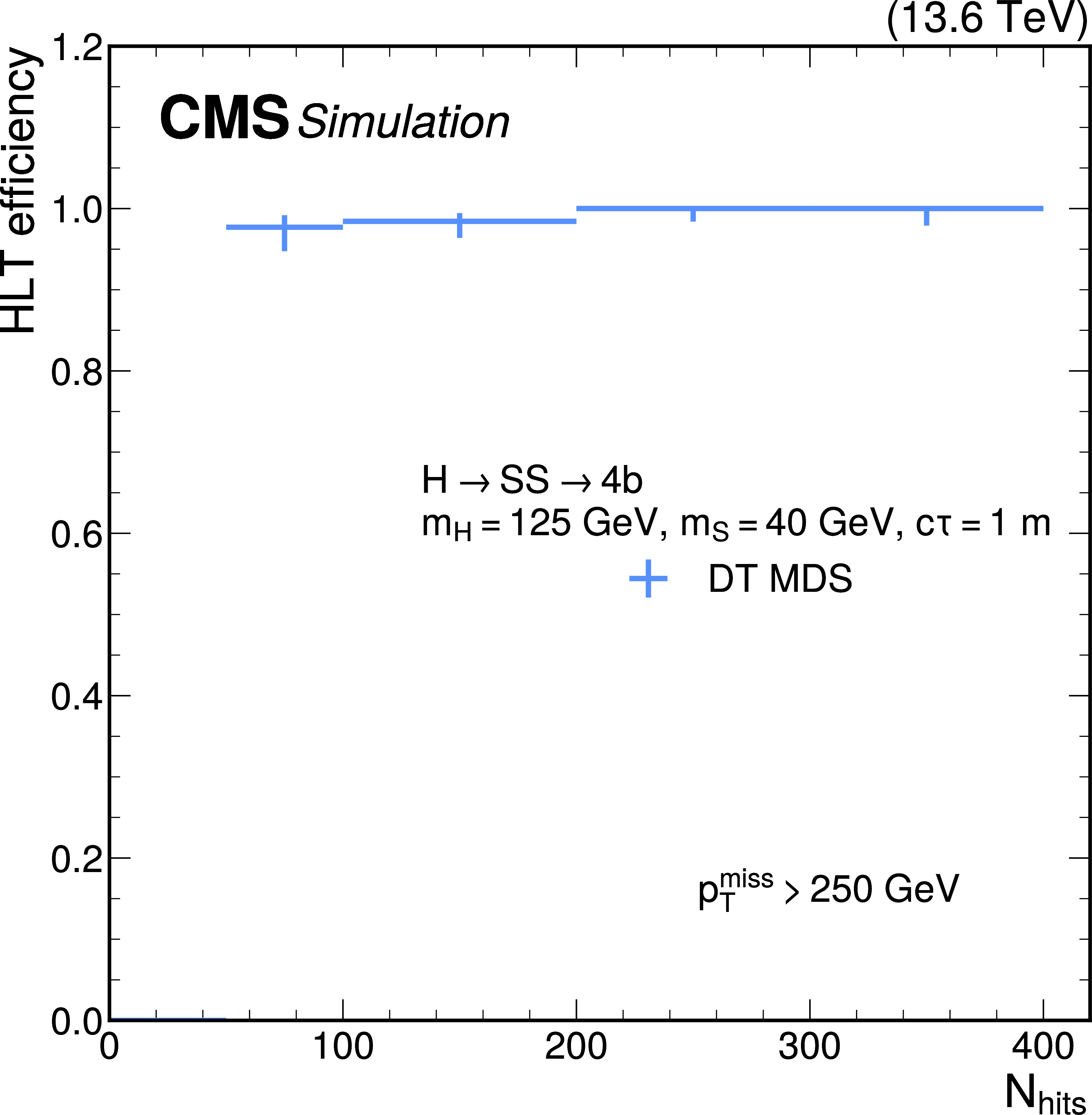

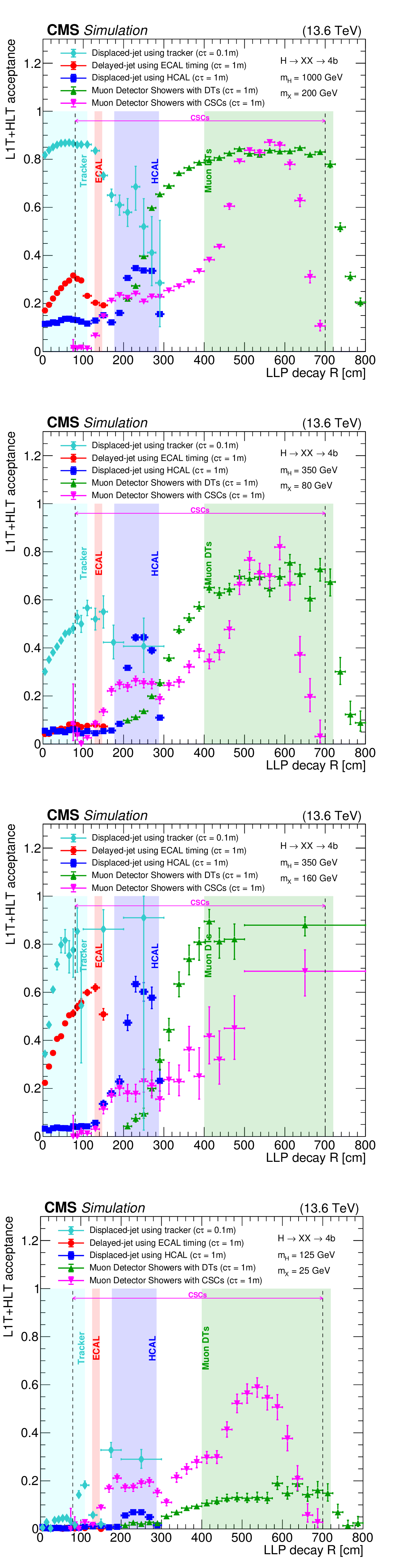

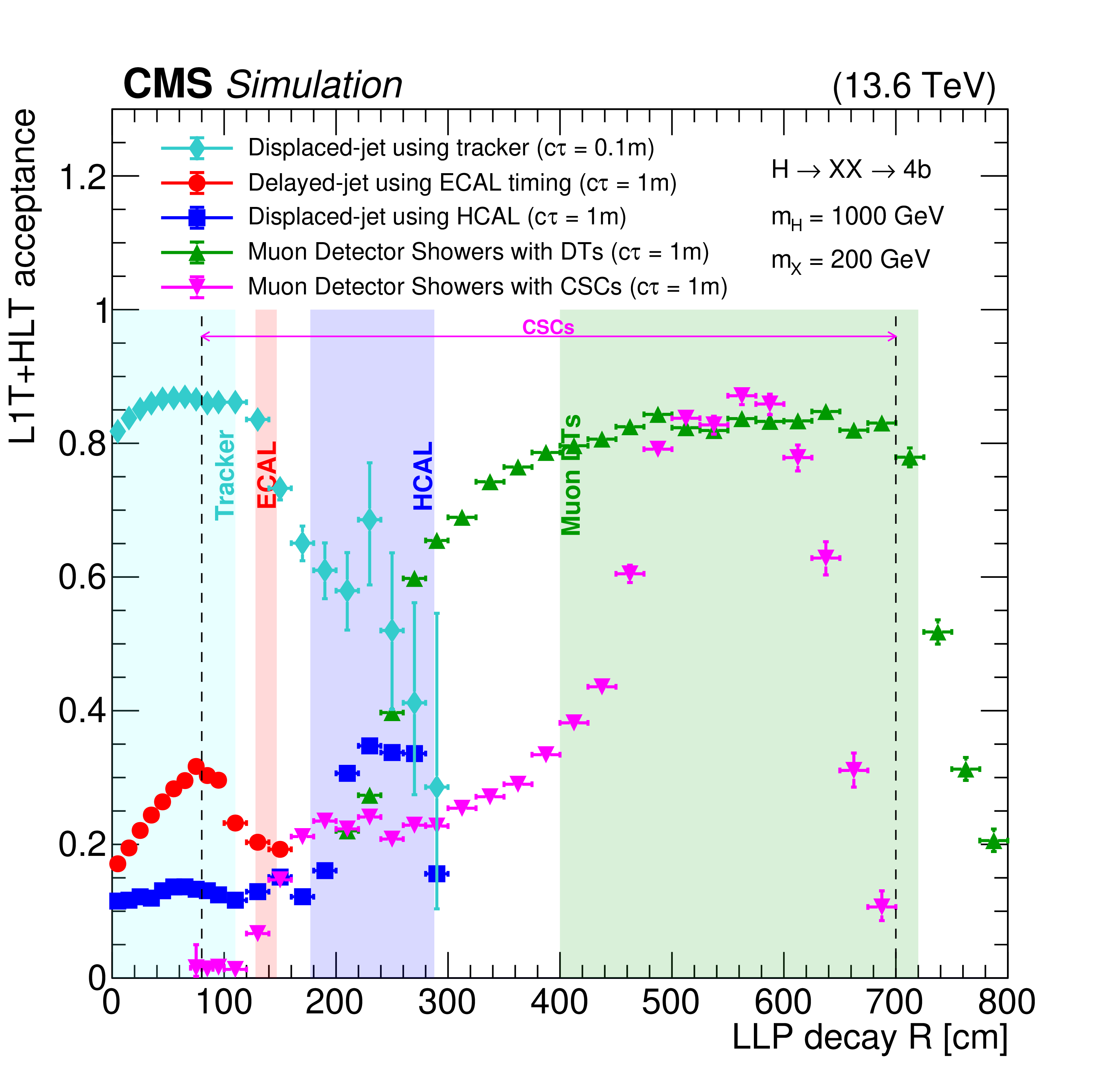

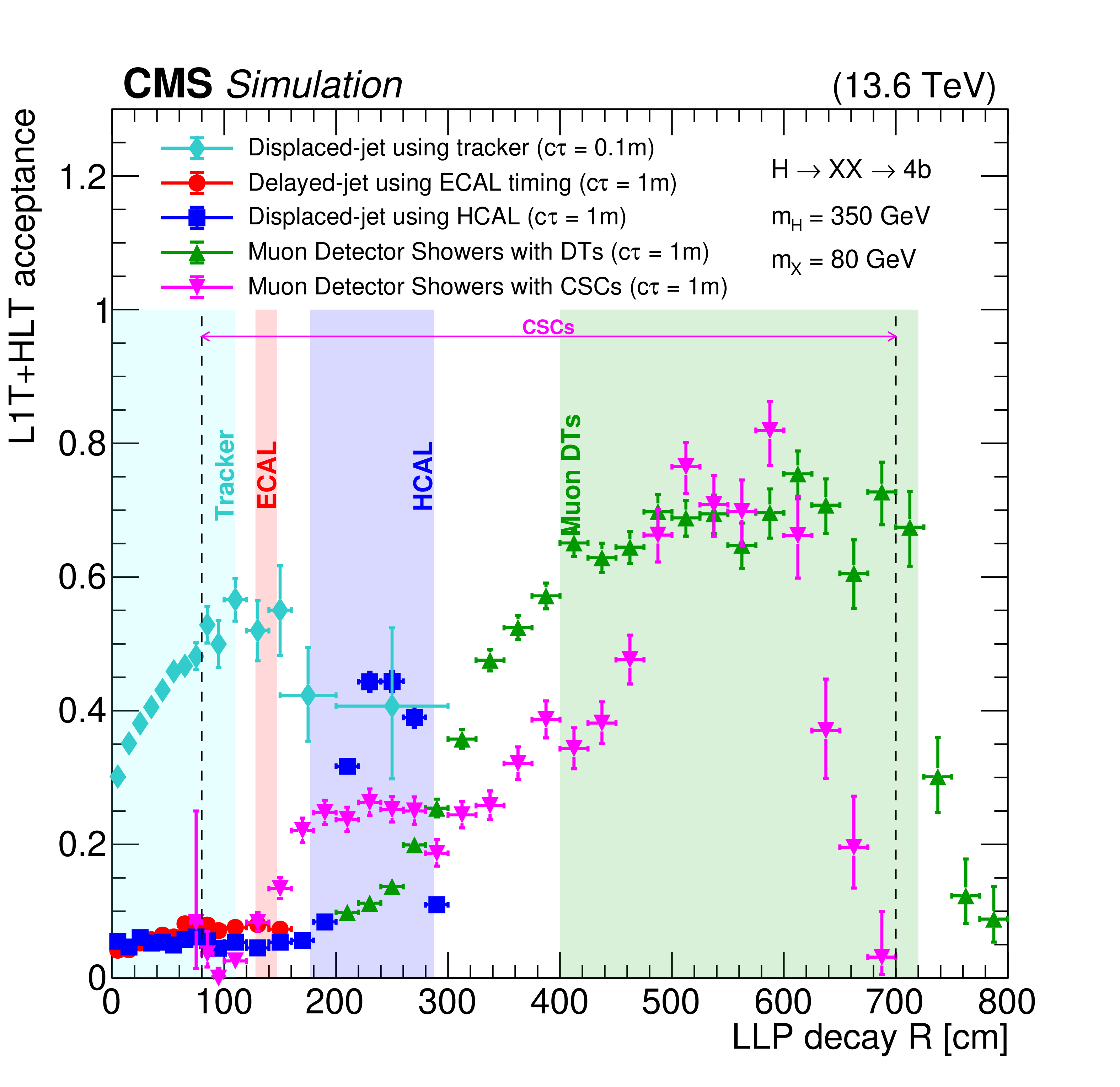

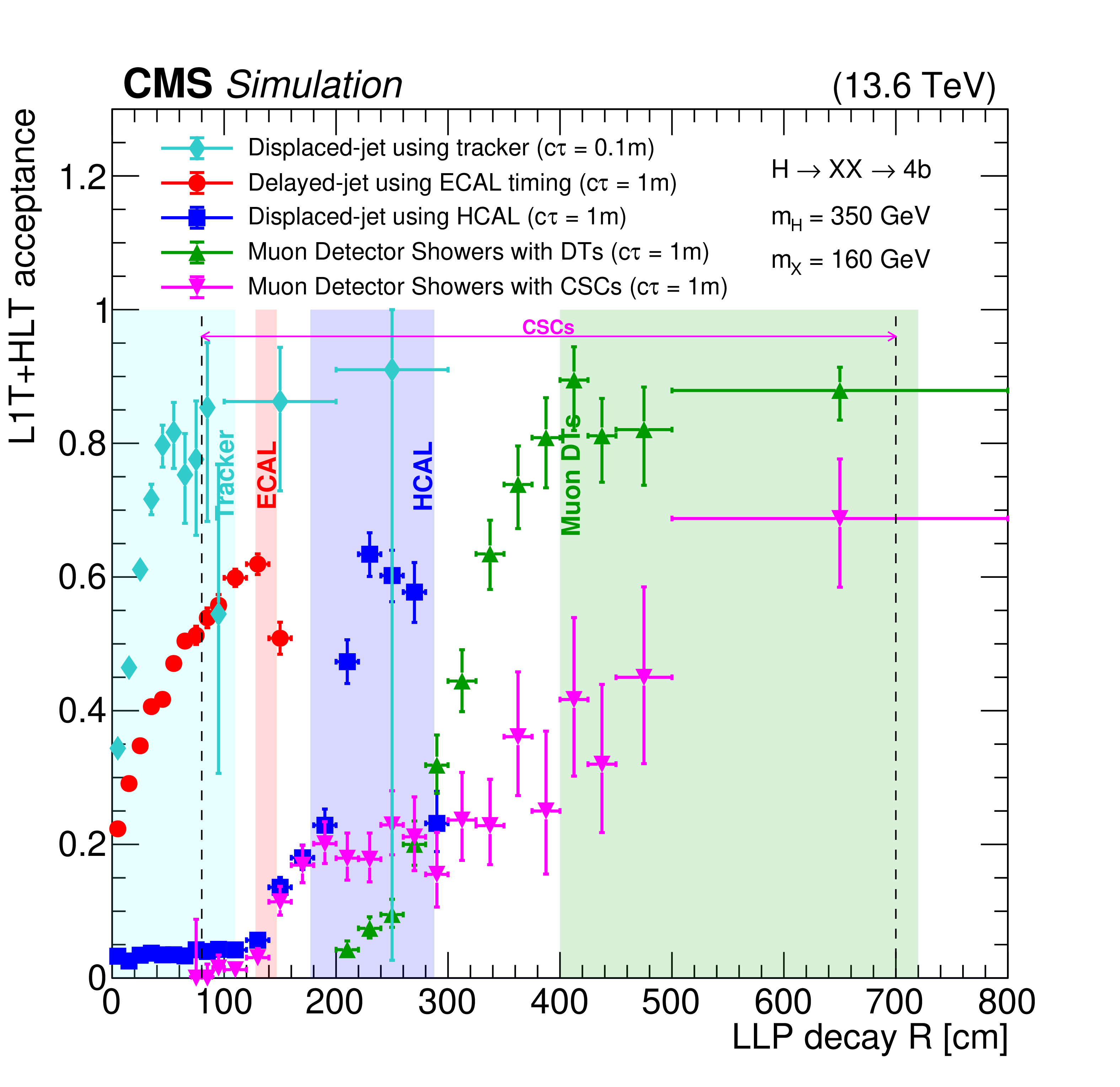

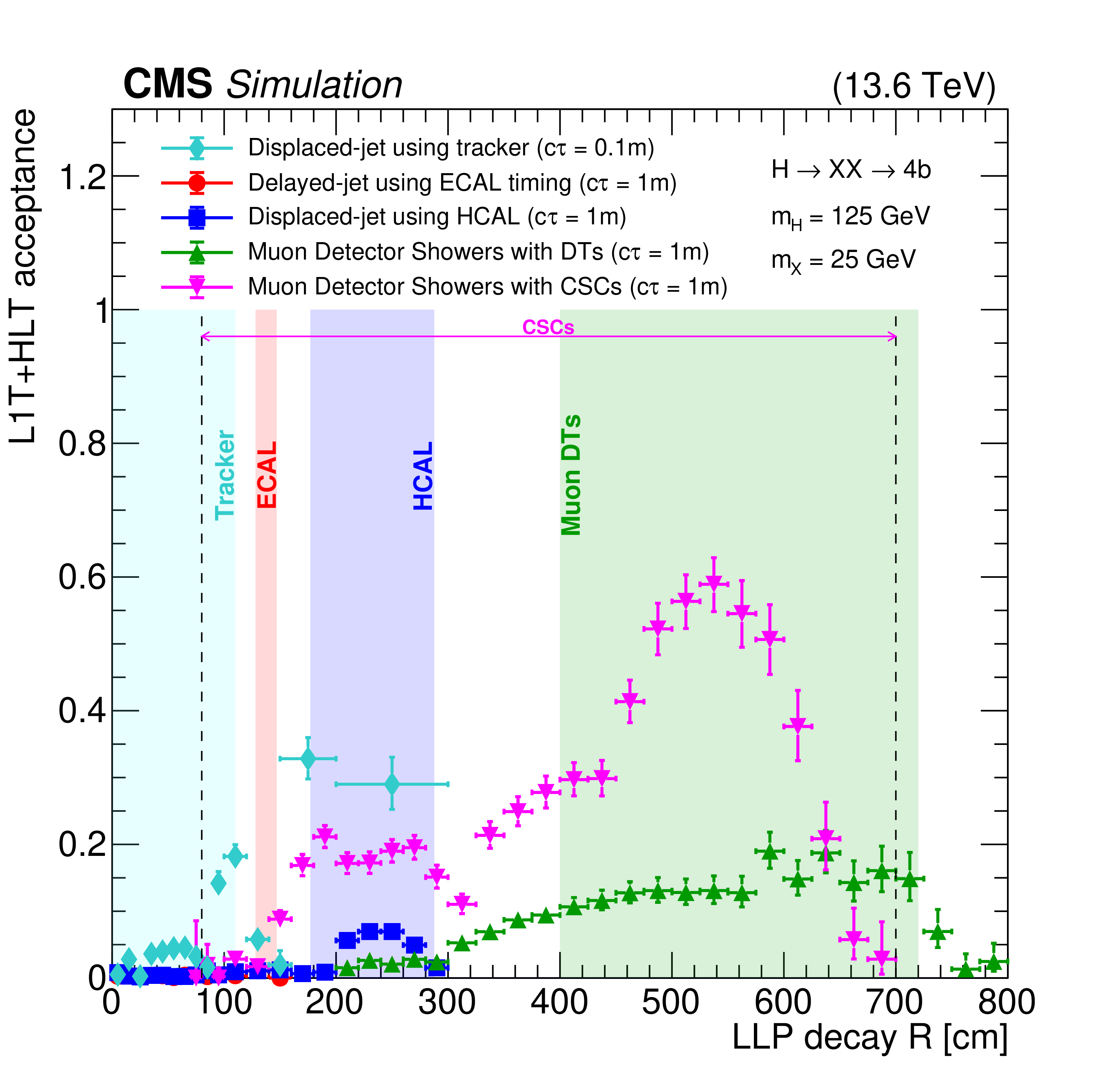

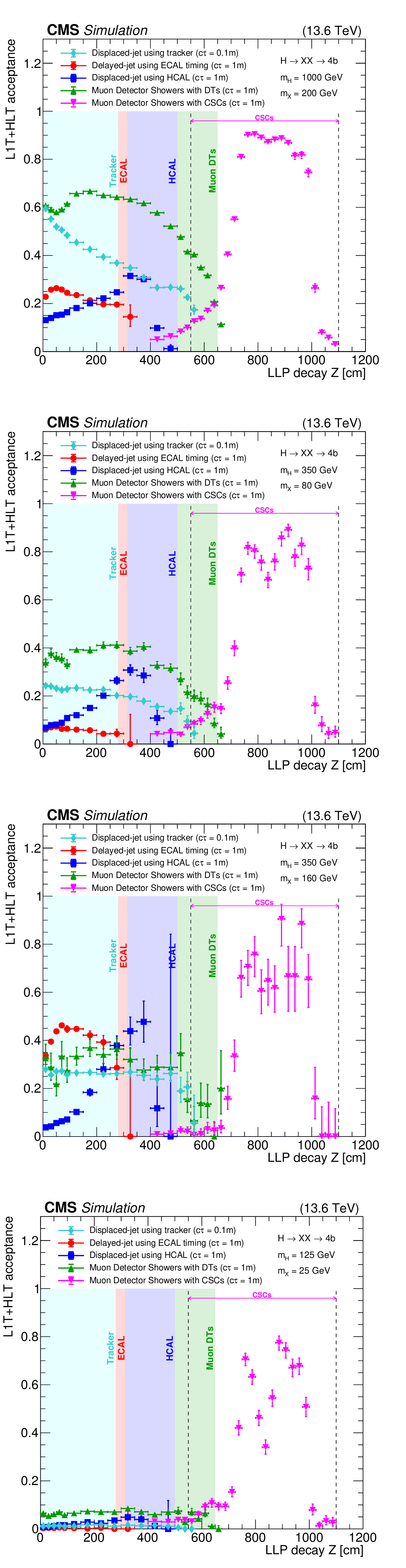

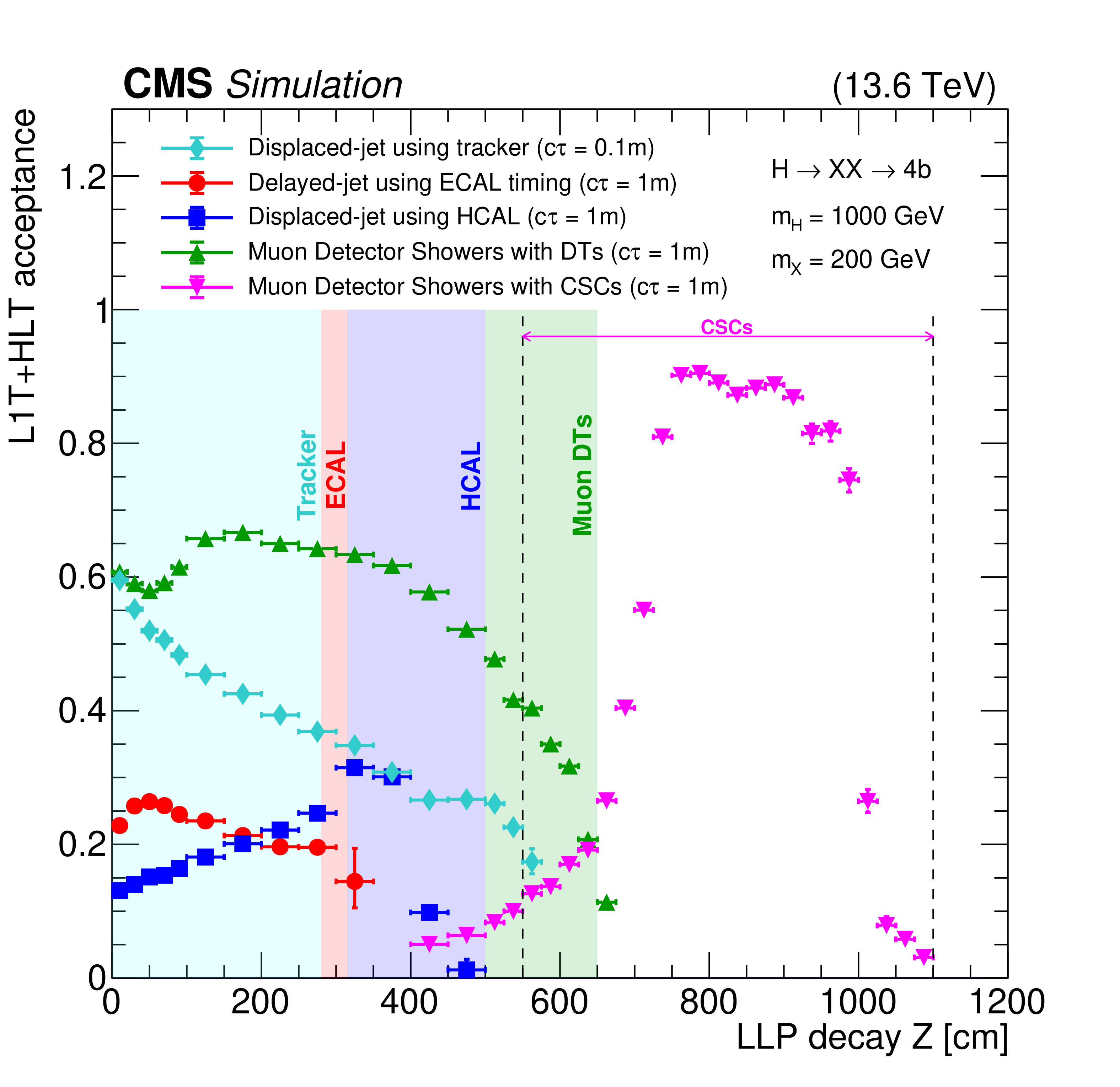

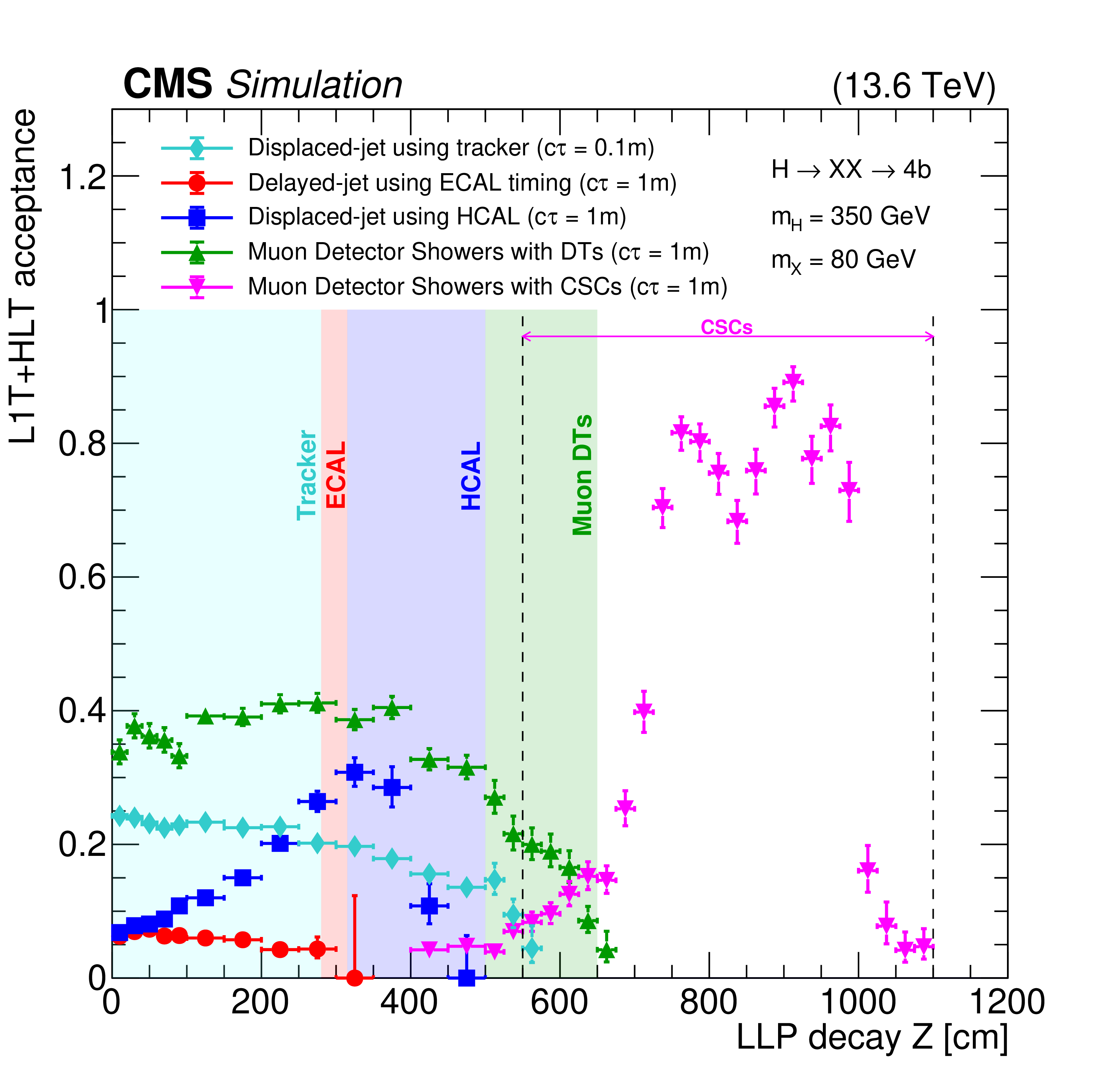

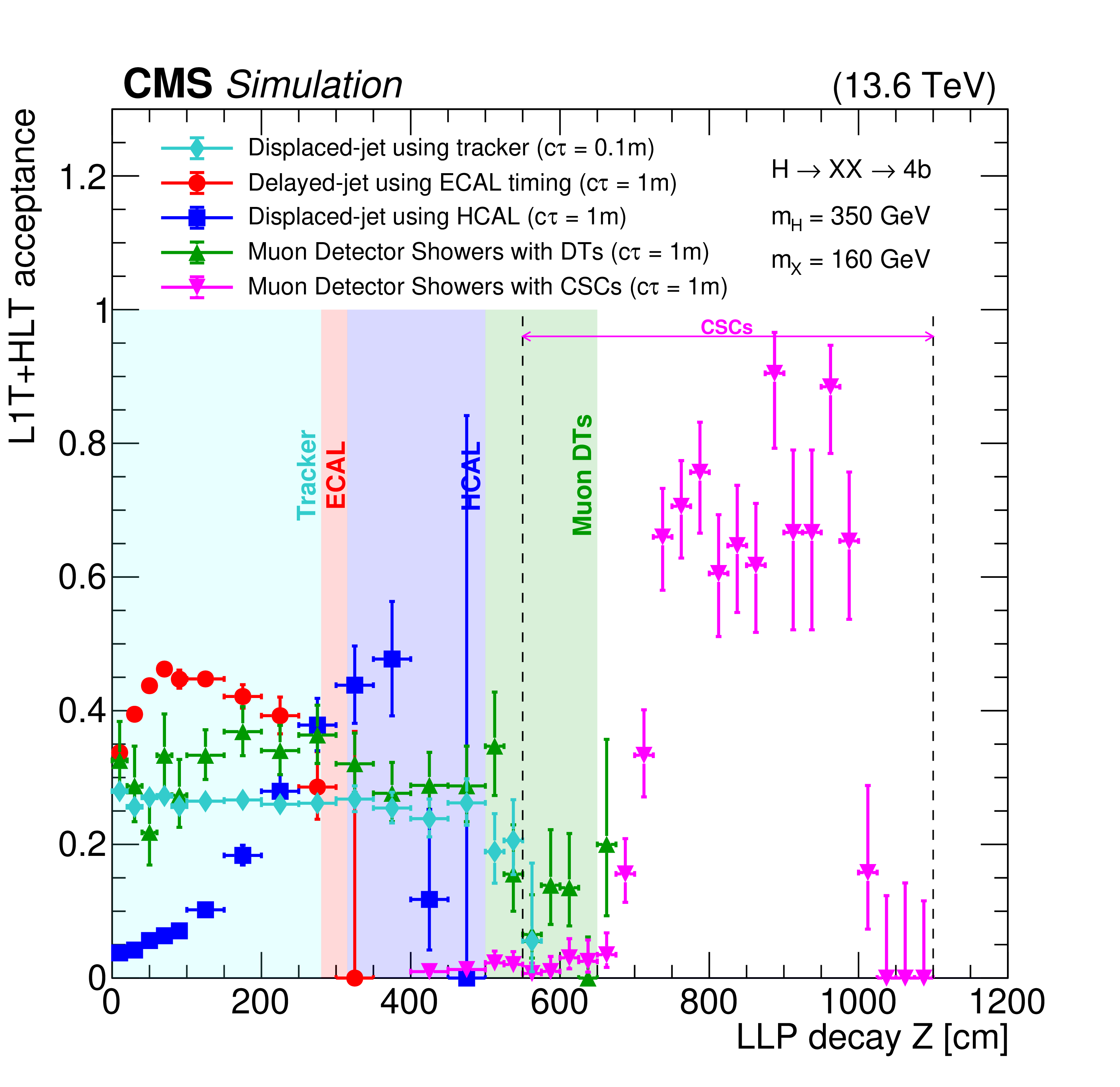

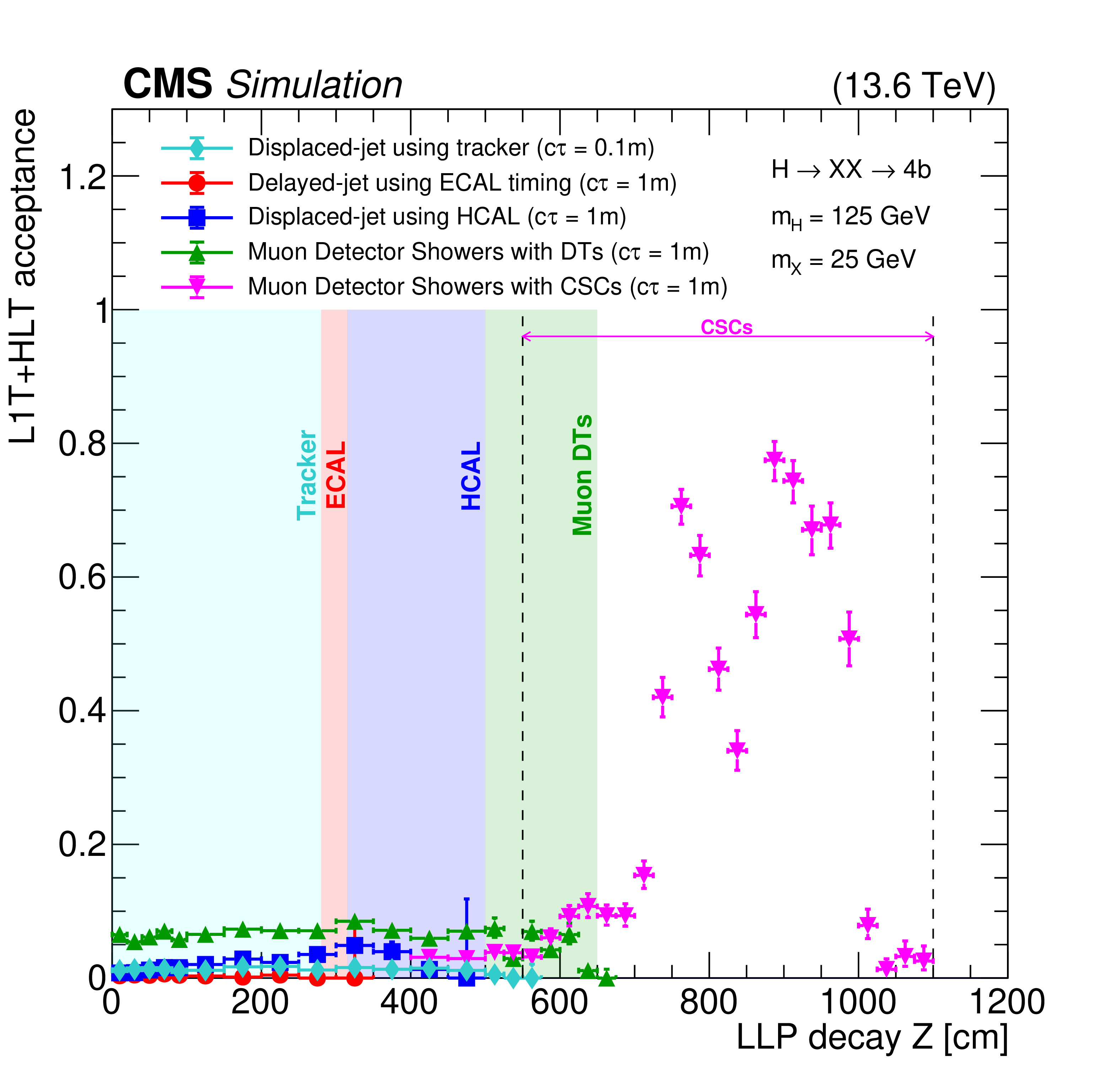

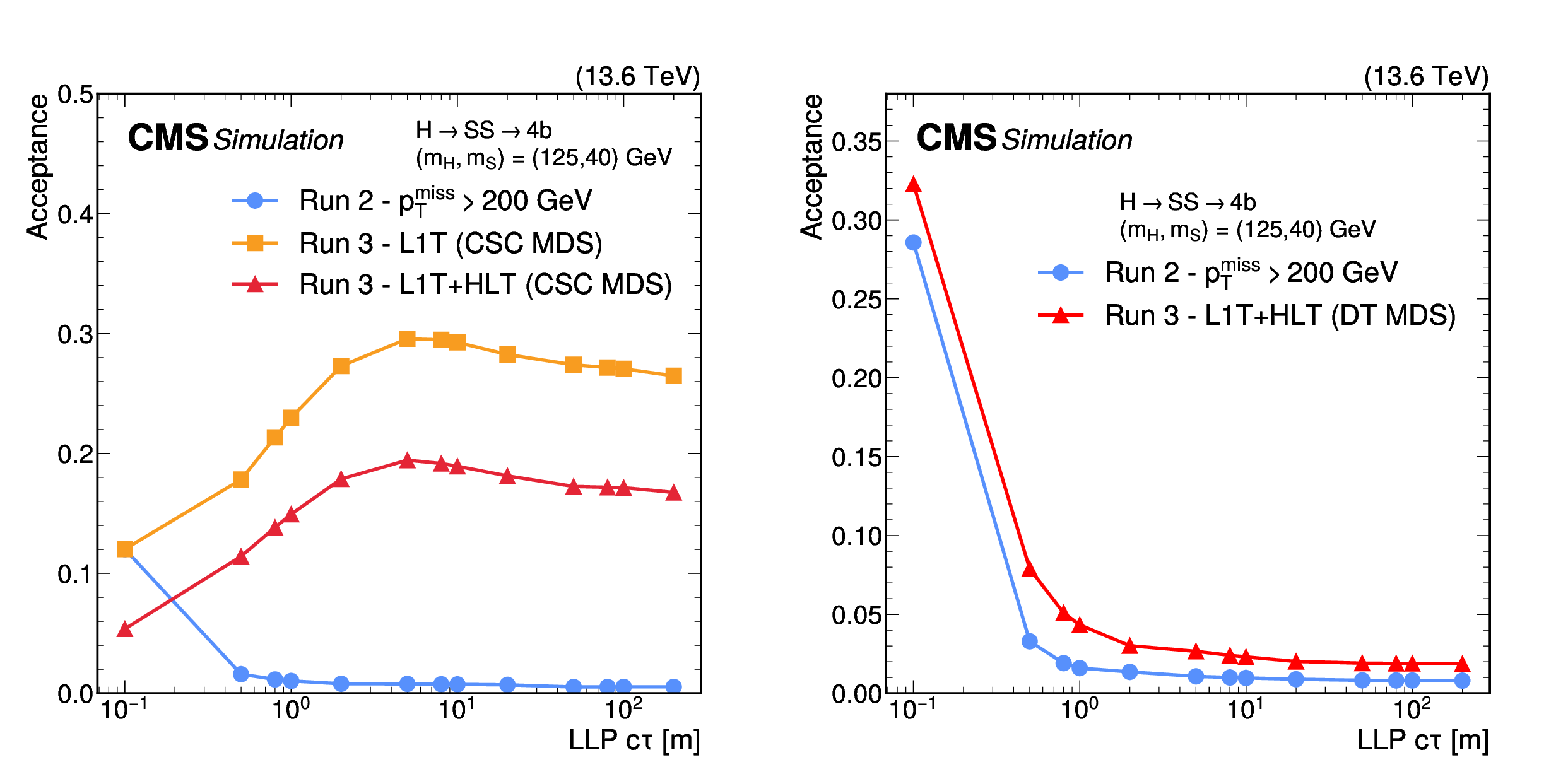

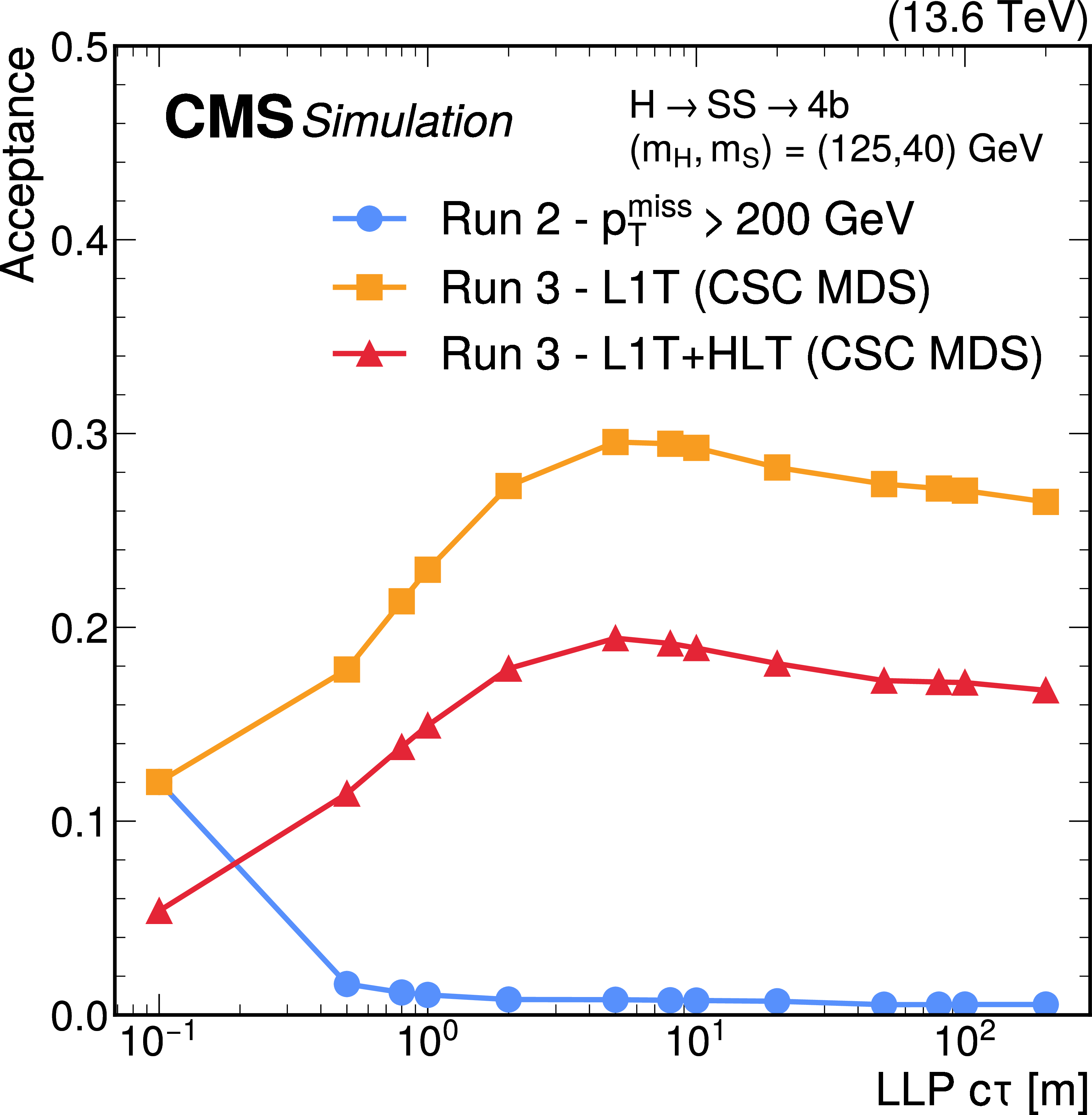

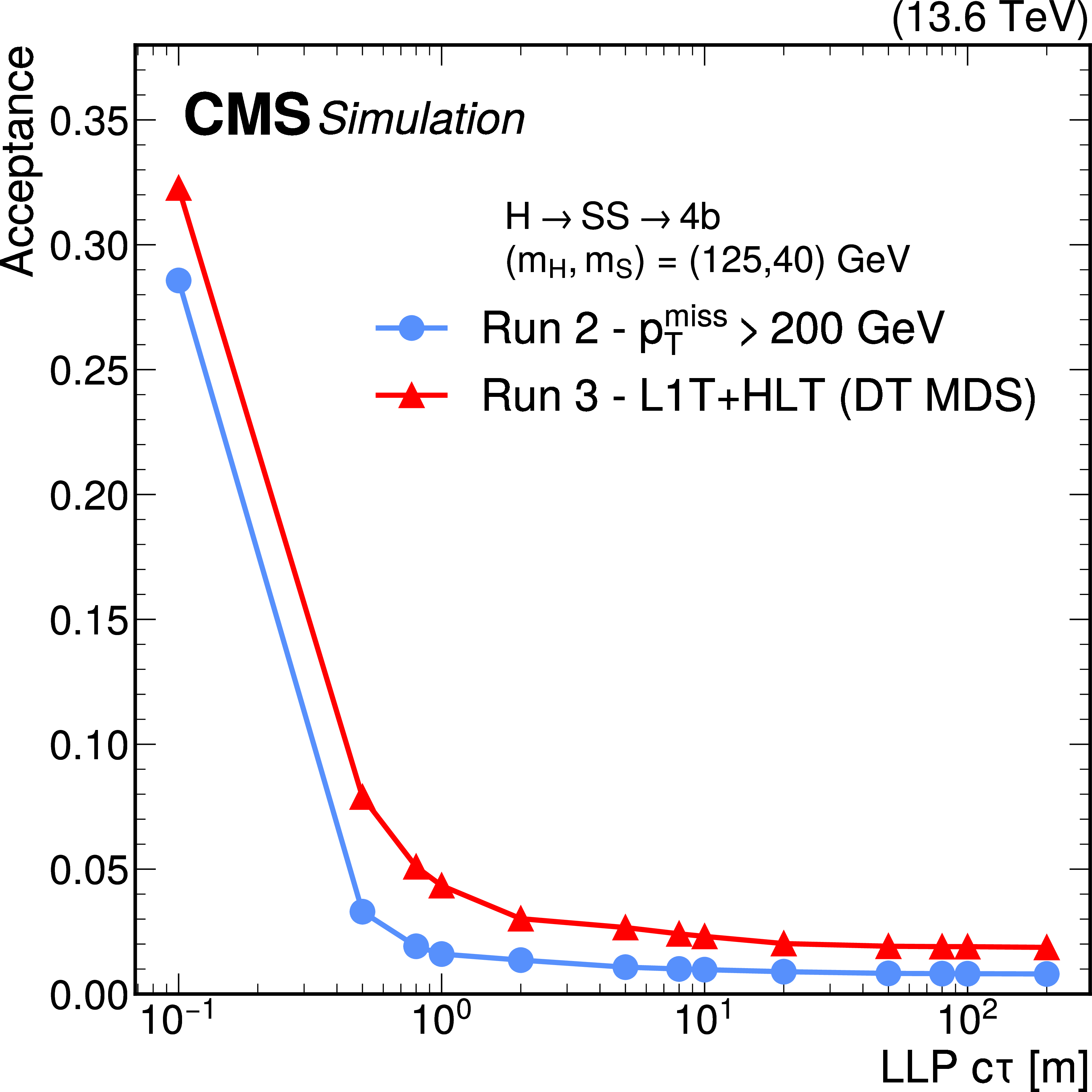

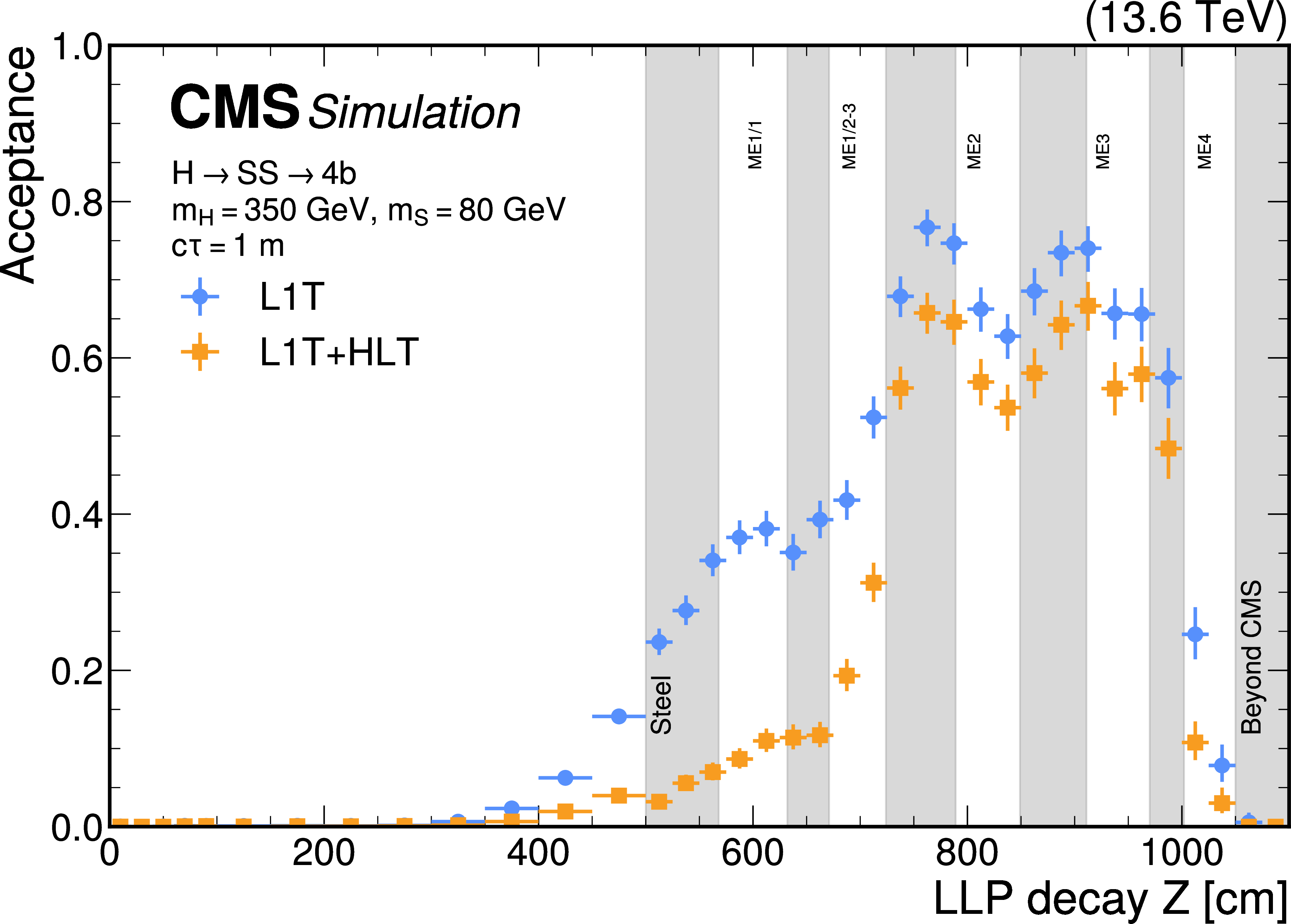

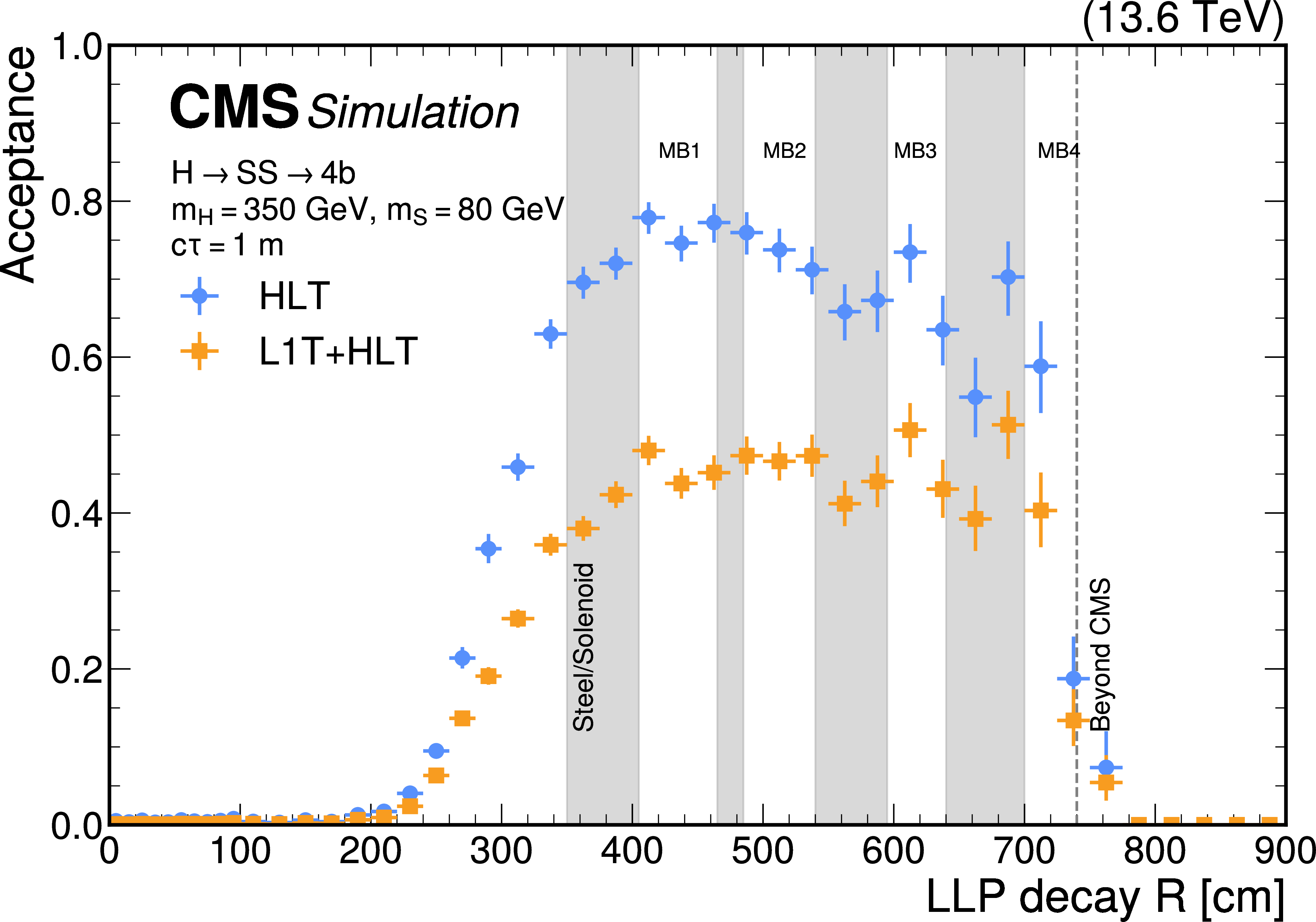

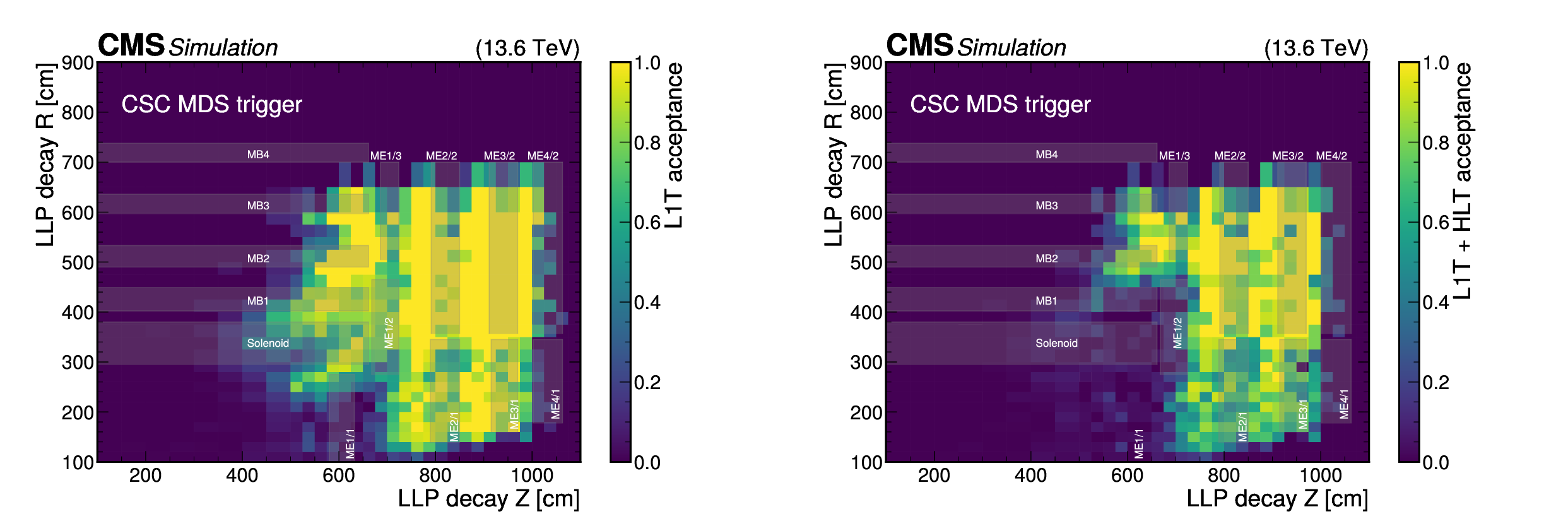

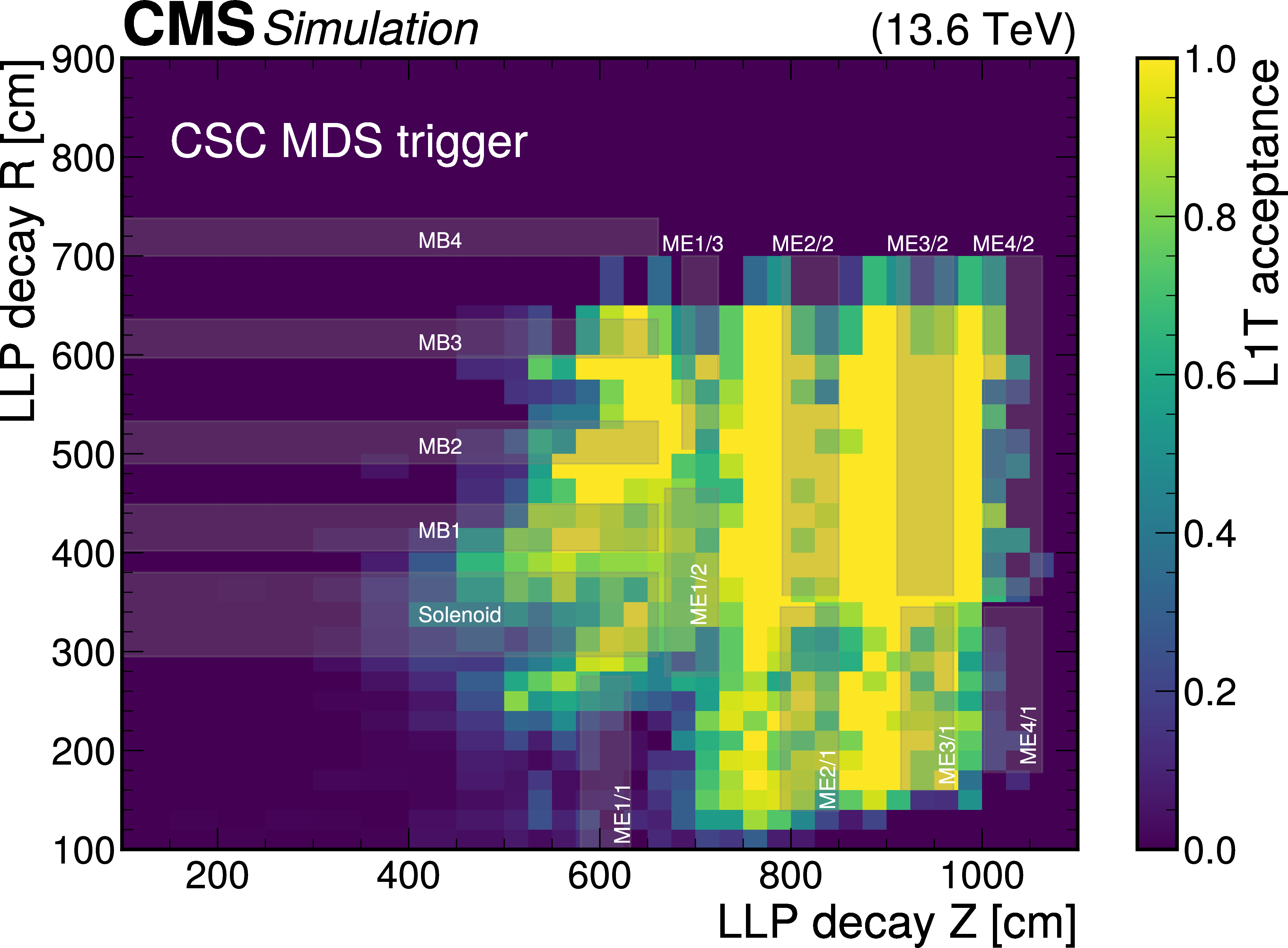

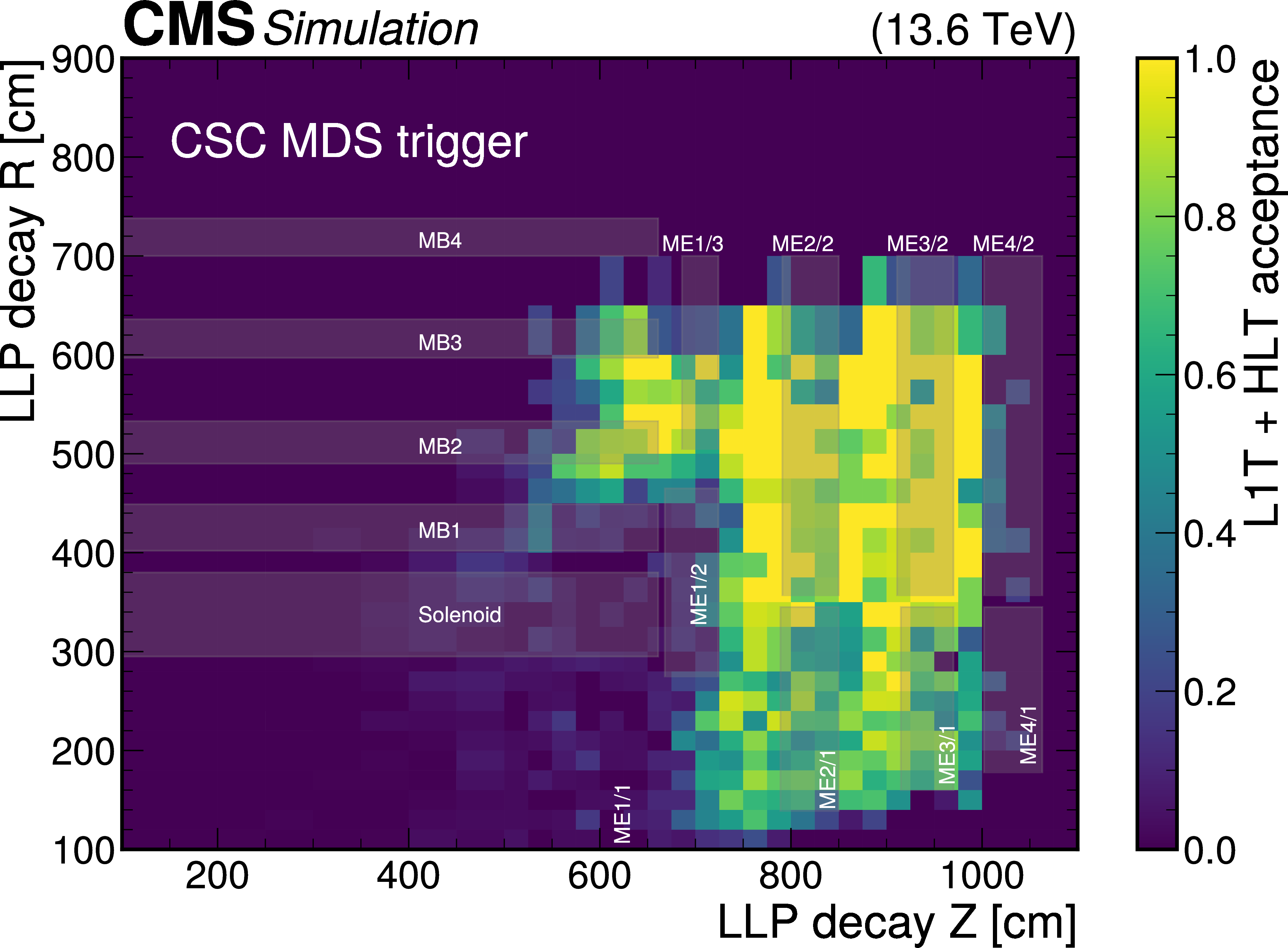

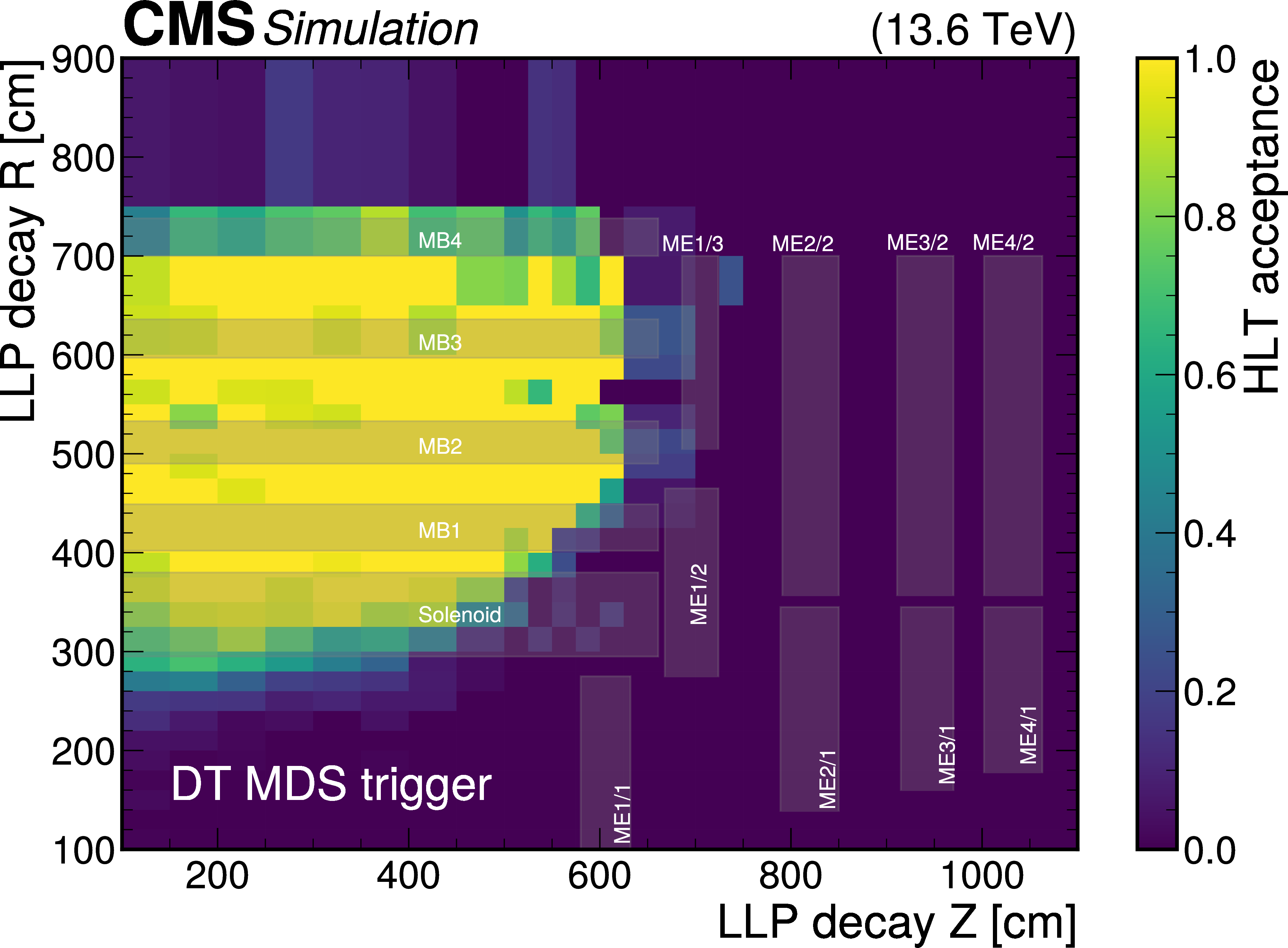

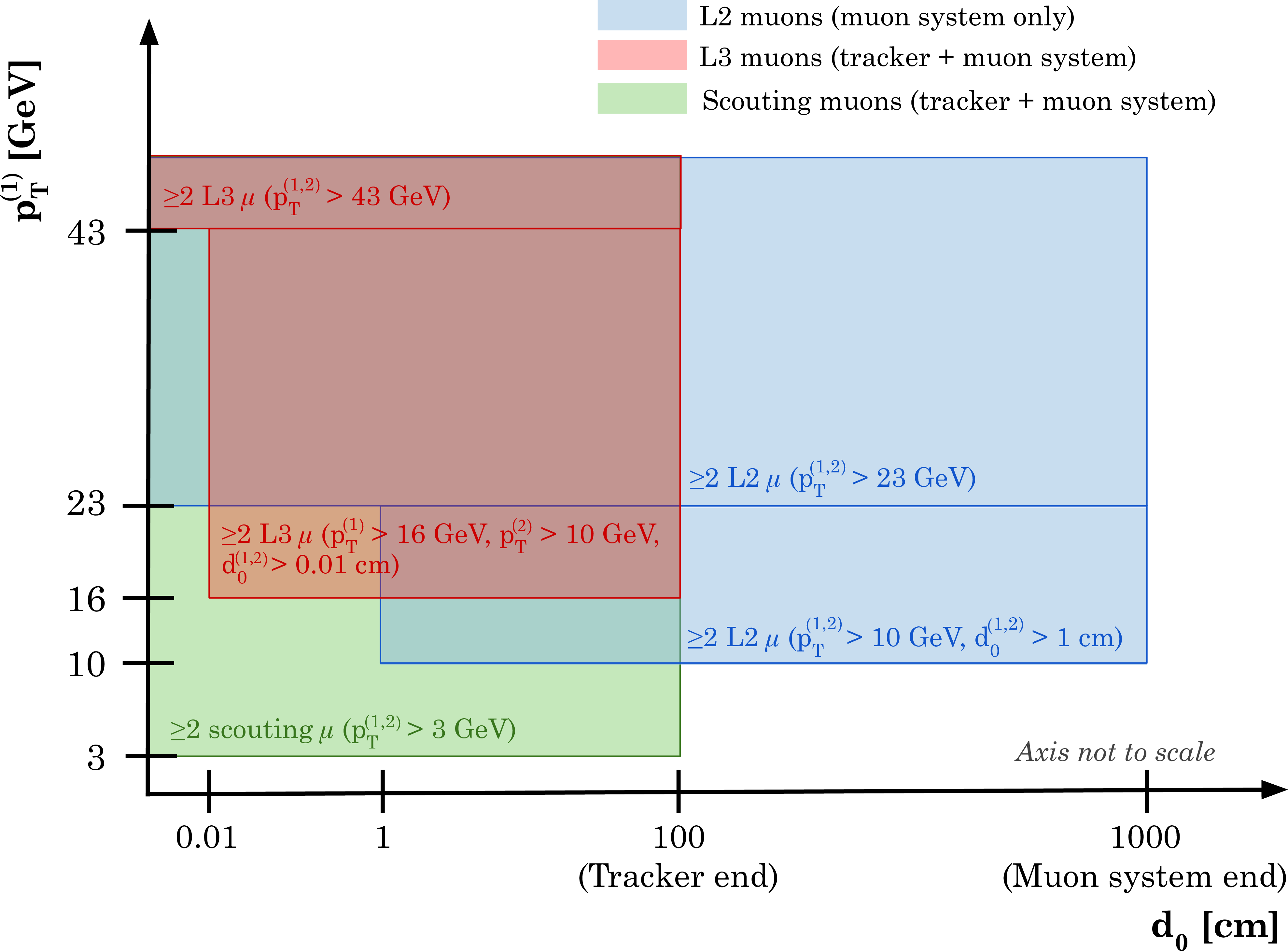

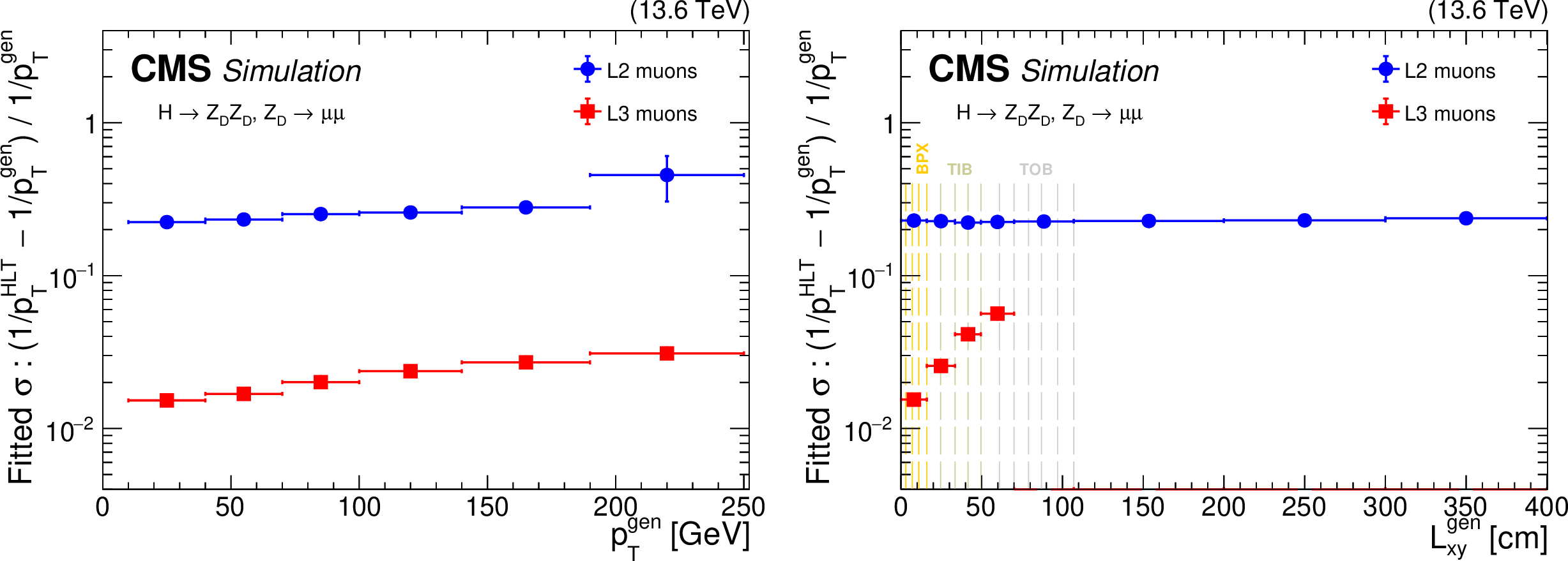

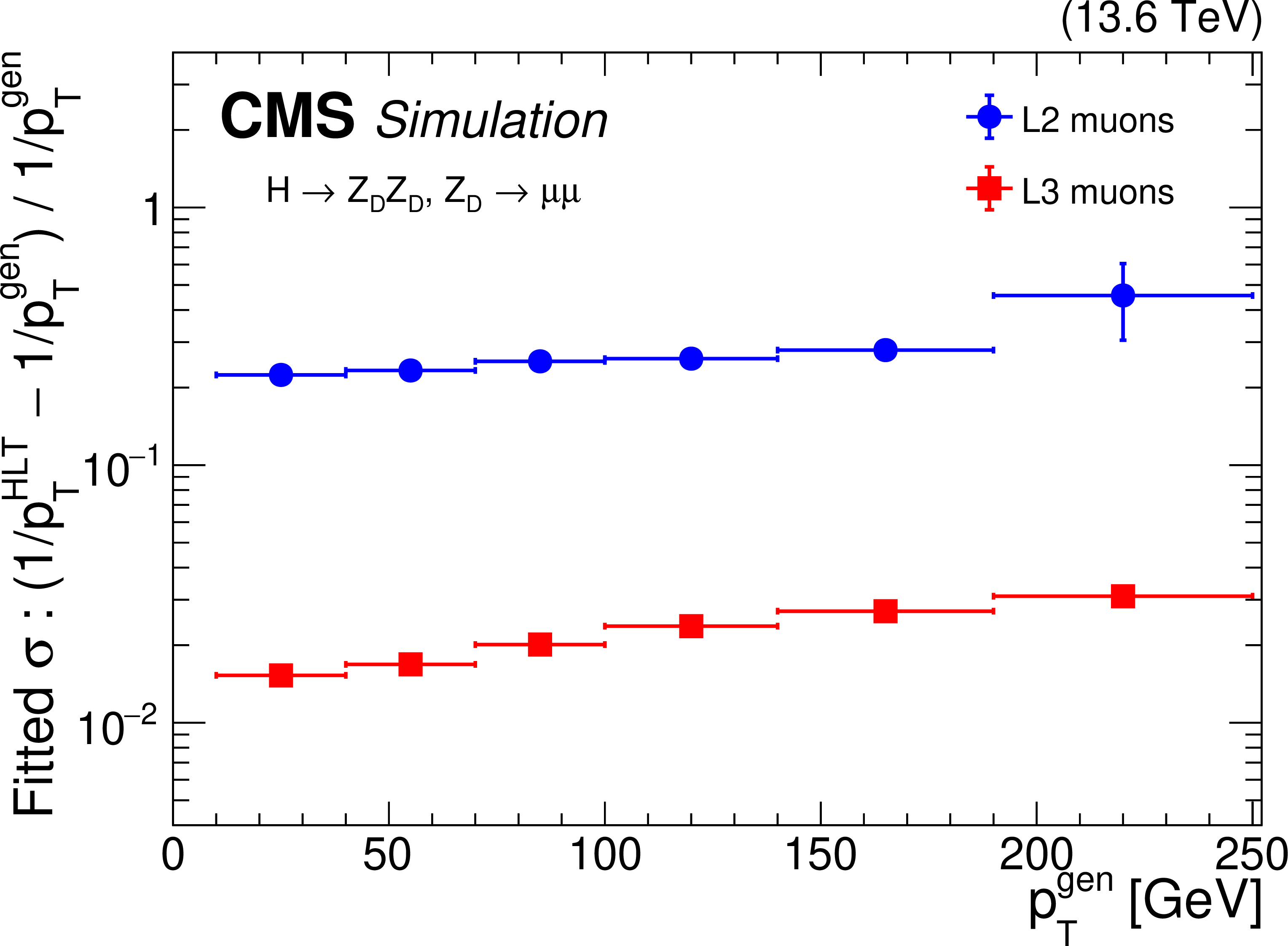

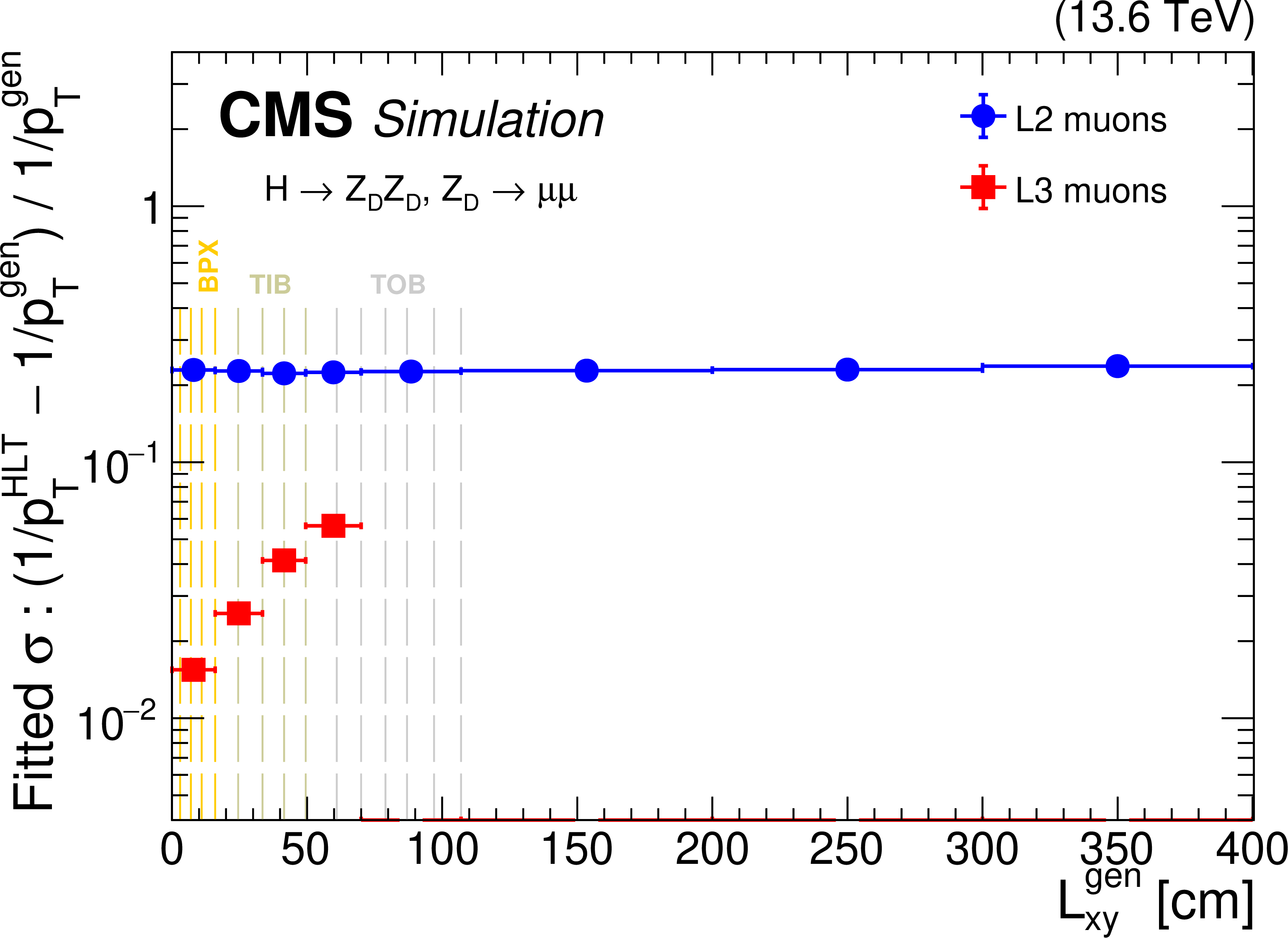

Figure 51-a: