Compact Muon Solenoid

LHC, CERN

| CMS-PFT-25-001 ; CERN-EP-2025-300 | ||

| Full event interpretation with machine-learning-based particle-flow reconstruction in the CMS detector | ||

| CMS Collaboration | ||

| 24 January 2026 | ||

| Submitted to Eur. Phys. J. C | ||

| Abstract: The particle-flow (PF) algorithm constructs a global description of each particle collision by producing a comprehensive list of final-state particles, and is central to event reconstruction in the CMS experiment at the CERN LHC. The existing PF implementation relies on physics-motivated heuristics and assumptions that can be replaced by machine-learning (ML) models trained directly on simulated data and naturally suited to modern graphics processing units (GPUs). A state-of-the-art ML-based PF (MLPF) reconstruction algorithm, implemented within the CMS software framework, is presented. The MLPF algorithm performs a learnable full-event reconstruction on GPUs, generalizes across detector conditions and collision energies, and replaces multiple modular reconstruction steps with a single unified model. Physics performance comparable to standard PF reconstruction is achieved in both simulation and data, with improved jet energy resolution and inference time. In simulated top quark-antiquark events under LHC Run-3 (2023-2024) conditions, the jet energy resolution improves by 10-20% for jets with transverse momentum between 30-100 GeV. Inference time is evaluated using simulated multijet events, with a median of 20 ms per event on an Nvidia L4 GPU, compared to approximately 110 ms for the standard CMS PF reconstruction. | ||

| Links: e-print arXiv:2601.17554 [hep-ex] (PDF) ; CDS record ; inSPIRE record ; CADI line (restricted) ; | ||

| Figures | |

png pdf |

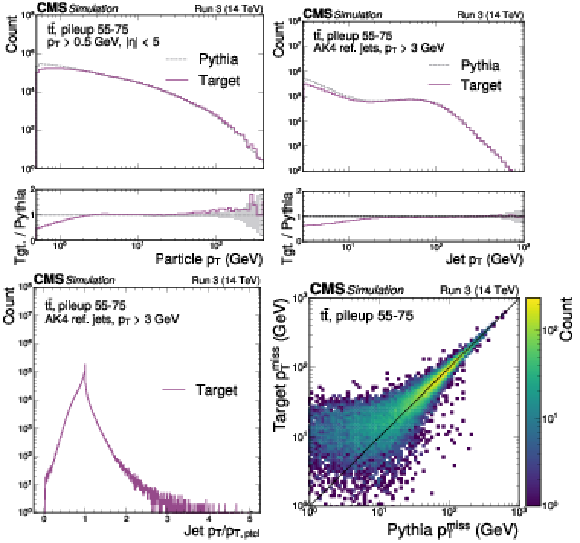

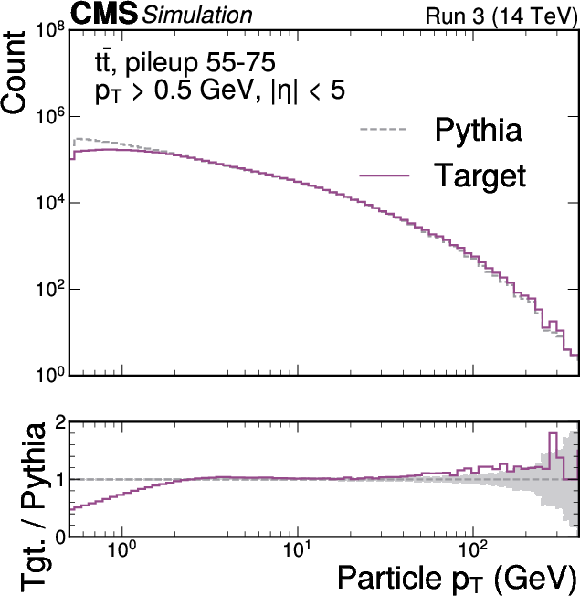

Figure 1:

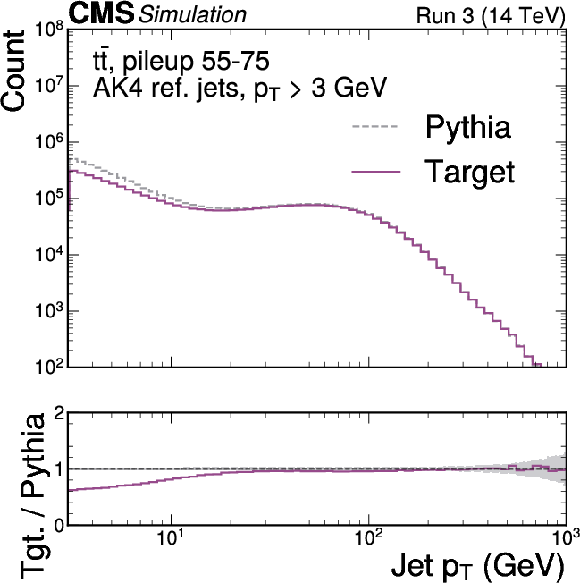

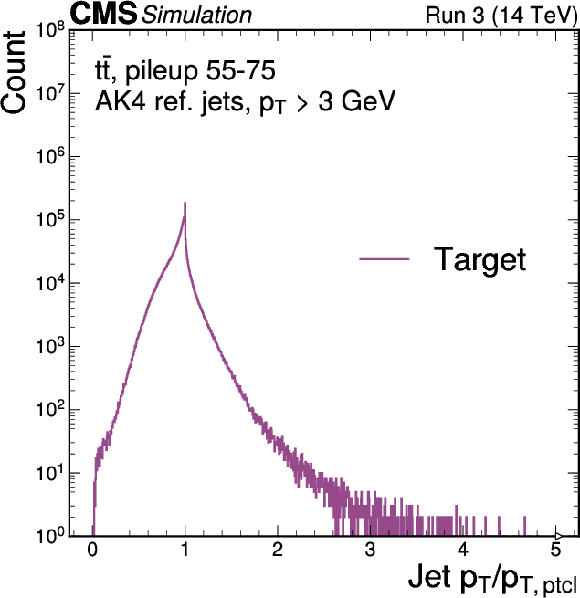

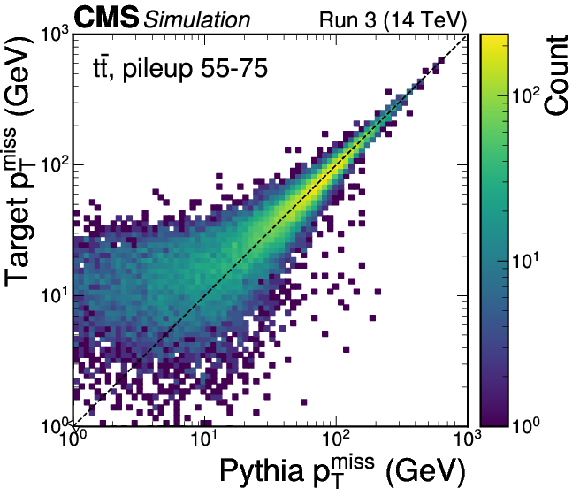

Validation of the MLPF particle-level target, after removing the contributions from the pileup particles, using $ \mathrm{t} \overline{\mathrm{t}} $ simulation with pileup. The $ p_{\mathrm{T}} $ distribution of target particles and truth particles derived from PYTHIA stable particles (upper left). The $ p_{\mathrm{T}} $ distribution of jets clustered from each particle set (upper right). The jet response relative to particle-level jets (lower left). The target $ p_{\mathrm{T}}^\text{miss} $ as a function of the PYTHIA truth $ p_{\mathrm{T}}^\text{miss} $ (lower right). The target particle set, after removing the contribution from pileup, generally aligns well with the pileup-free PYTHIA truth. |

png pdf |

Figure 1-a:

Validation of the MLPF particle-level target, after removing the contributions from the pileup particles, using $ \mathrm{t} \overline{\mathrm{t}} $ simulation with pileup. The $ p_{\mathrm{T}} $ distribution of target particles and truth particles derived from PYTHIA stable particles (upper left). The $ p_{\mathrm{T}} $ distribution of jets clustered from each particle set (upper right). The jet response relative to particle-level jets (lower left). The target $ p_{\mathrm{T}}^\text{miss} $ as a function of the PYTHIA truth $ p_{\mathrm{T}}^\text{miss} $ (lower right). The target particle set, after removing the contribution from pileup, generally aligns well with the pileup-free PYTHIA truth. |

png pdf |

Figure 1-b:

Validation of the MLPF particle-level target, after removing the contributions from the pileup particles, using $ \mathrm{t} \overline{\mathrm{t}} $ simulation with pileup. The $ p_{\mathrm{T}} $ distribution of target particles and truth particles derived from PYTHIA stable particles (upper left). The $ p_{\mathrm{T}} $ distribution of jets clustered from each particle set (upper right). The jet response relative to particle-level jets (lower left). The target $ p_{\mathrm{T}}^\text{miss} $ as a function of the PYTHIA truth $ p_{\mathrm{T}}^\text{miss} $ (lower right). The target particle set, after removing the contribution from pileup, generally aligns well with the pileup-free PYTHIA truth. |

png pdf |

Figure 1-c:

Validation of the MLPF particle-level target, after removing the contributions from the pileup particles, using $ \mathrm{t} \overline{\mathrm{t}} $ simulation with pileup. The $ p_{\mathrm{T}} $ distribution of target particles and truth particles derived from PYTHIA stable particles (upper left). The $ p_{\mathrm{T}} $ distribution of jets clustered from each particle set (upper right). The jet response relative to particle-level jets (lower left). The target $ p_{\mathrm{T}}^\text{miss} $ as a function of the PYTHIA truth $ p_{\mathrm{T}}^\text{miss} $ (lower right). The target particle set, after removing the contribution from pileup, generally aligns well with the pileup-free PYTHIA truth. |

png pdf |

Figure 1-d:

Validation of the MLPF particle-level target, after removing the contributions from the pileup particles, using $ \mathrm{t} \overline{\mathrm{t}} $ simulation with pileup. The $ p_{\mathrm{T}} $ distribution of target particles and truth particles derived from PYTHIA stable particles (upper left). The $ p_{\mathrm{T}} $ distribution of jets clustered from each particle set (upper right). The jet response relative to particle-level jets (lower left). The target $ p_{\mathrm{T}}^\text{miss} $ as a function of the PYTHIA truth $ p_{\mathrm{T}}^\text{miss} $ (lower right). The target particle set, after removing the contribution from pileup, generally aligns well with the pileup-free PYTHIA truth. |

png pdf |

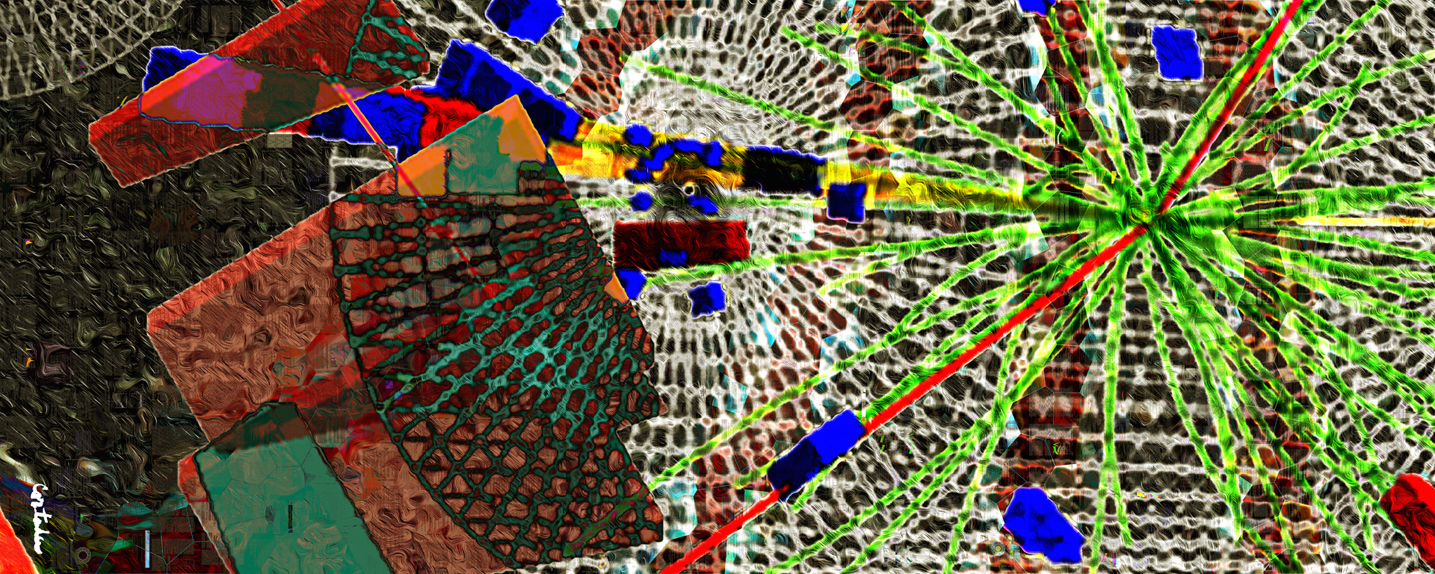

Figure 2:

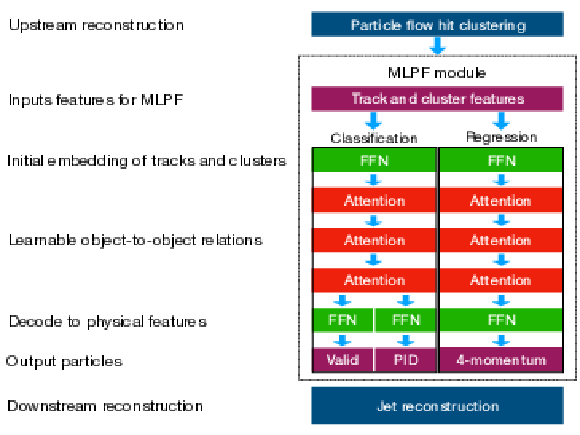

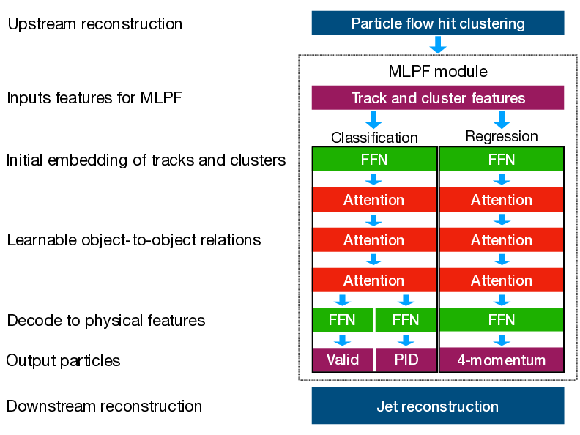

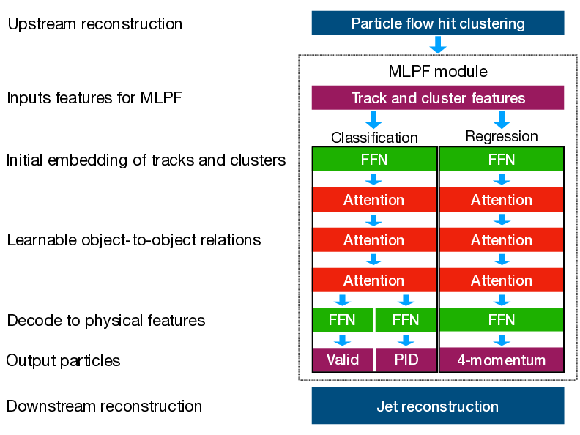

The neural network structure of the model. Input and output features are visualized in purple. Pointwise FFNs are visualized in green, and layers with full-event correlations in red. The last dimension contains a binary output to predict the presence of a particle (Valid), multi-class outputs for the PID, and the predicted momentum values. |

png pdf |

Figure 2-a:

The neural network structure of the model. Input and output features are visualized in purple. Pointwise FFNs are visualized in green, and layers with full-event correlations in red. The last dimension contains a binary output to predict the presence of a particle (Valid), multi-class outputs for the PID, and the predicted momentum values. |

png pdf |

Figure 2-b:

The neural network structure of the model. Input and output features are visualized in purple. Pointwise FFNs are visualized in green, and layers with full-event correlations in red. The last dimension contains a binary output to predict the presence of a particle (Valid), multi-class outputs for the PID, and the predicted momentum values. |

png pdf |

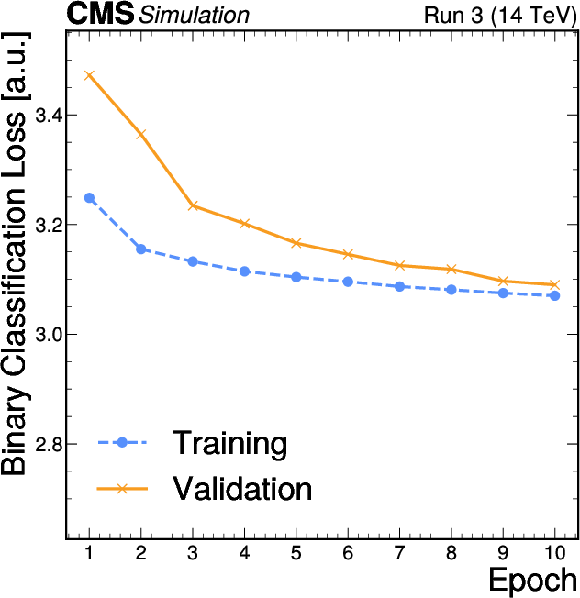

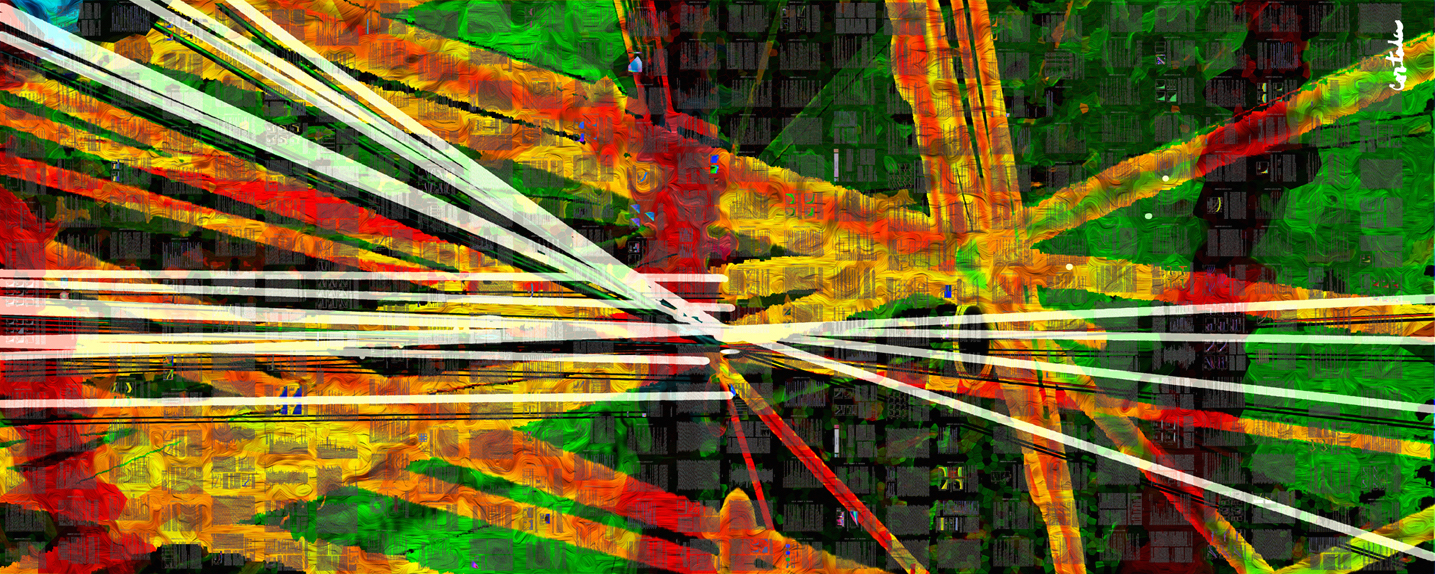

Figure 3:

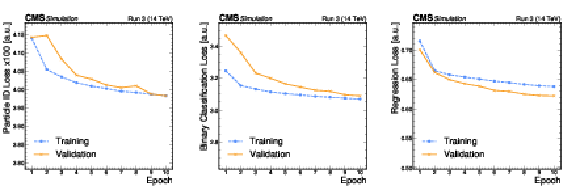

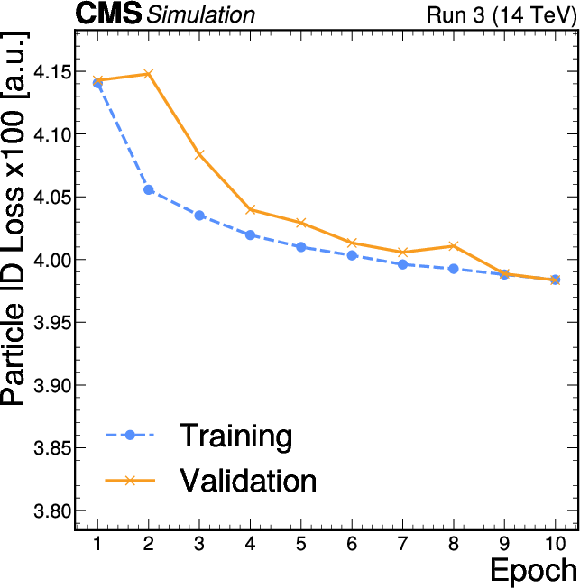

The PID, binary classification, and regression losses for the training and validation data sets, as a function of the training epoch. We observe both the training and validation losses to be smoothly converging. The training loss is evaluated with a partially-trained model throughout the training epoch on the training events (80%), while the validation loss is computed with the model weights at the end of the epoch on the validation events (20%). The losses are measured in arbitrary units, averaged across the events. |

png pdf |

Figure 3-a:

The PID, binary classification, and regression losses for the training and validation data sets, as a function of the training epoch. We observe both the training and validation losses to be smoothly converging. The training loss is evaluated with a partially-trained model throughout the training epoch on the training events (80%), while the validation loss is computed with the model weights at the end of the epoch on the validation events (20%). The losses are measured in arbitrary units, averaged across the events. |

png pdf |

Figure 3-b:

The PID, binary classification, and regression losses for the training and validation data sets, as a function of the training epoch. We observe both the training and validation losses to be smoothly converging. The training loss is evaluated with a partially-trained model throughout the training epoch on the training events (80%), while the validation loss is computed with the model weights at the end of the epoch on the validation events (20%). The losses are measured in arbitrary units, averaged across the events. |

png pdf |

Figure 3-c:

The PID, binary classification, and regression losses for the training and validation data sets, as a function of the training epoch. We observe both the training and validation losses to be smoothly converging. The training loss is evaluated with a partially-trained model throughout the training epoch on the training events (80%), while the validation loss is computed with the model weights at the end of the epoch on the validation events (20%). The losses are measured in arbitrary units, averaged across the events. |

png pdf |

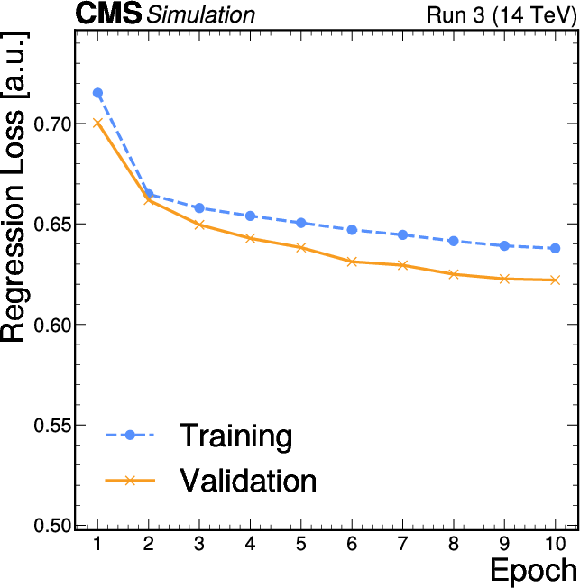

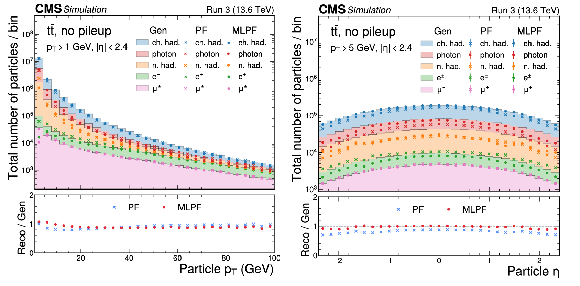

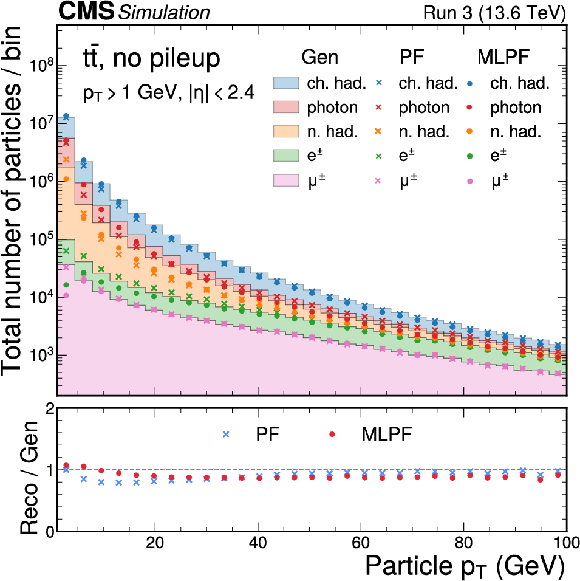

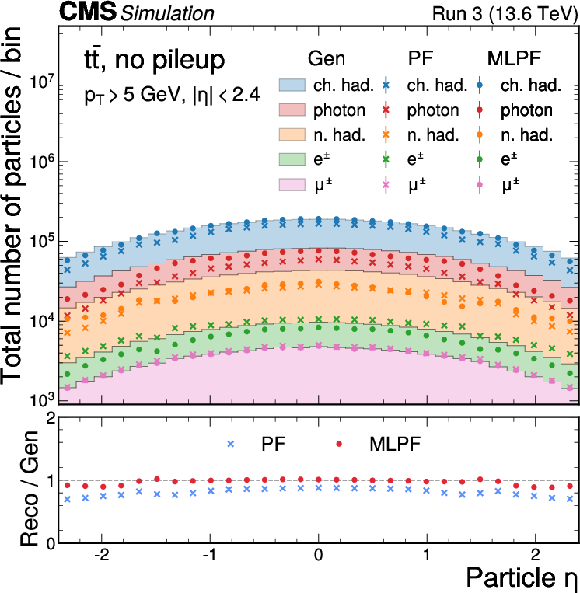

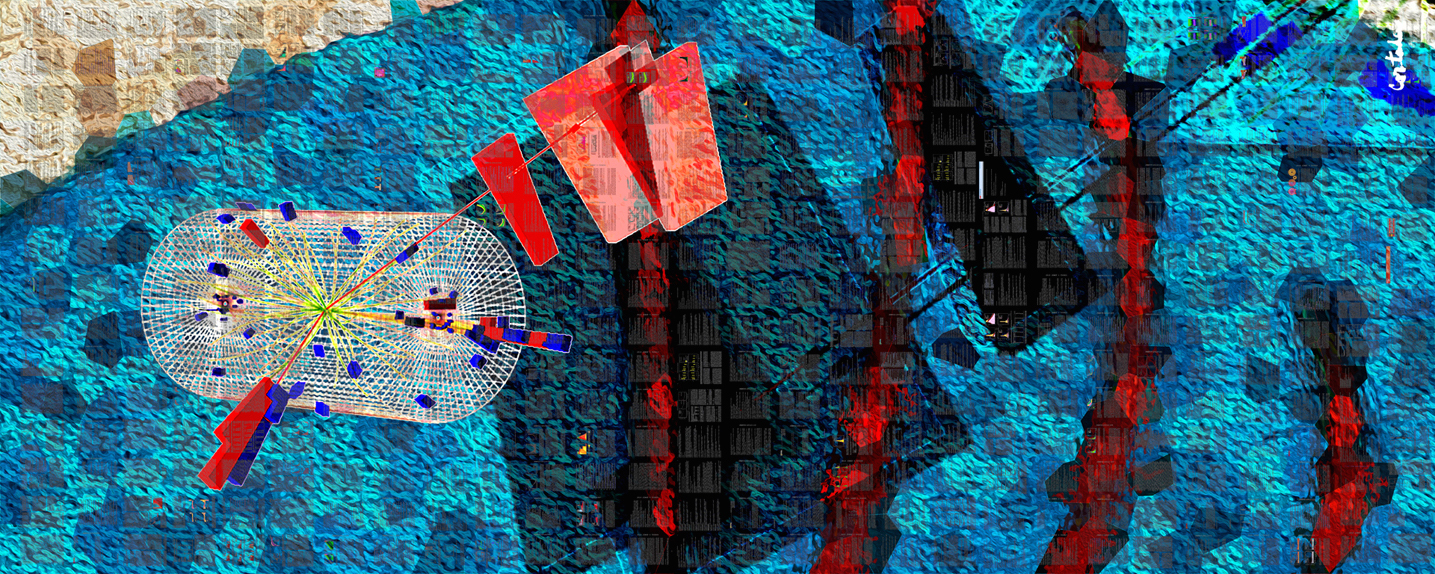

Figure 4:

The particle $ p_{\mathrm{T}} $ (left) and $ \eta $ (right) distributions split by PID for MC particles (Gen), and PF and MLPF candidates in $ \mathrm{t} \overline{\mathrm{t}} $ events. In the forward region, the PF and MLPF algorithms do not attempt to identify particles, but instead reconstruct the deposits as either electromagnetic or hadronic. |

png pdf |

Figure 4-a:

The particle $ p_{\mathrm{T}} $ (left) and $ \eta $ (right) distributions split by PID for MC particles (Gen), and PF and MLPF candidates in $ \mathrm{t} \overline{\mathrm{t}} $ events. In the forward region, the PF and MLPF algorithms do not attempt to identify particles, but instead reconstruct the deposits as either electromagnetic or hadronic. |

png pdf |

Figure 4-b:

The particle $ p_{\mathrm{T}} $ (left) and $ \eta $ (right) distributions split by PID for MC particles (Gen), and PF and MLPF candidates in $ \mathrm{t} \overline{\mathrm{t}} $ events. In the forward region, the PF and MLPF algorithms do not attempt to identify particles, but instead reconstruct the deposits as either electromagnetic or hadronic. |

png pdf |

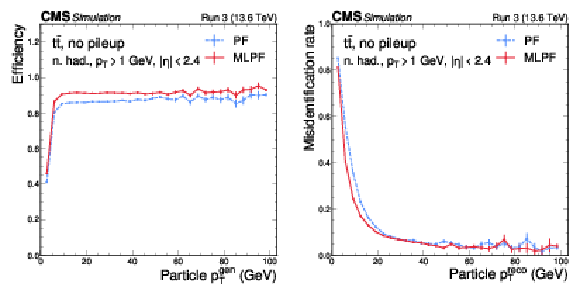

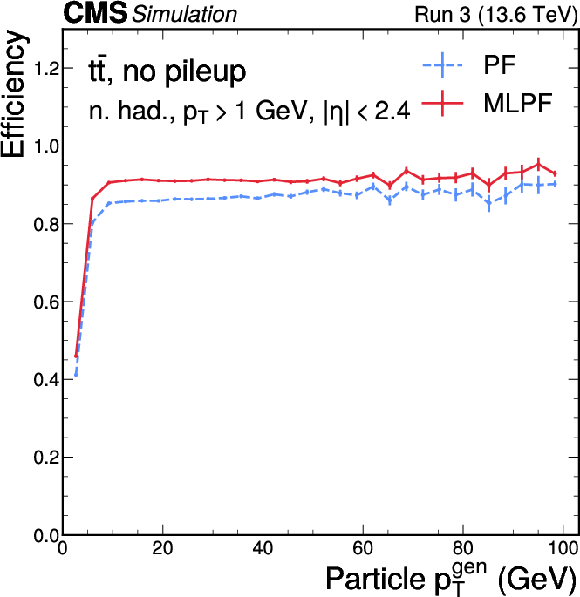

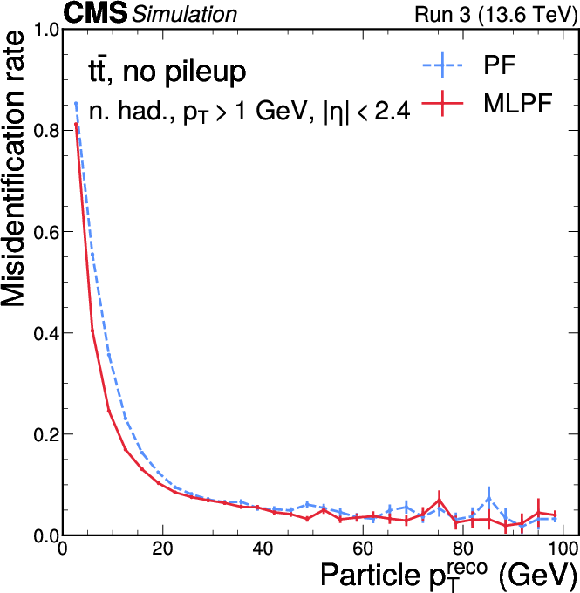

Figure 5:

Neutral hadron efficiency (left) and misidentification rate (right) as functions of $ p_{\mathrm{T}} $ for PF (blue) and MLPF (red) in $ \mathrm{t} \overline{\mathrm{t}} $ events based on $ \Delta R $ matching to generator-level particles. The MLPF algorithm generally has higher efficiency at a lower misidentification rate. The vertical bars indicate the statistical uncertainties on the respective distributions. |

png pdf |

Figure 5-a:

Neutral hadron efficiency (left) and misidentification rate (right) as functions of $ p_{\mathrm{T}} $ for PF (blue) and MLPF (red) in $ \mathrm{t} \overline{\mathrm{t}} $ events based on $ \Delta R $ matching to generator-level particles. The MLPF algorithm generally has higher efficiency at a lower misidentification rate. The vertical bars indicate the statistical uncertainties on the respective distributions. |

png pdf |

Figure 5-b:

Neutral hadron efficiency (left) and misidentification rate (right) as functions of $ p_{\mathrm{T}} $ for PF (blue) and MLPF (red) in $ \mathrm{t} \overline{\mathrm{t}} $ events based on $ \Delta R $ matching to generator-level particles. The MLPF algorithm generally has higher efficiency at a lower misidentification rate. The vertical bars indicate the statistical uncertainties on the respective distributions. |

png pdf |

Figure 6:

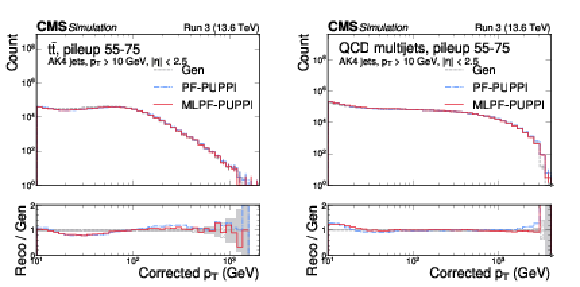

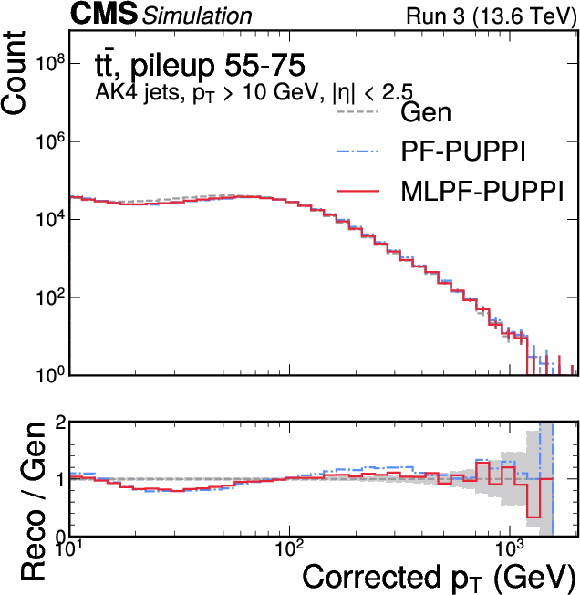

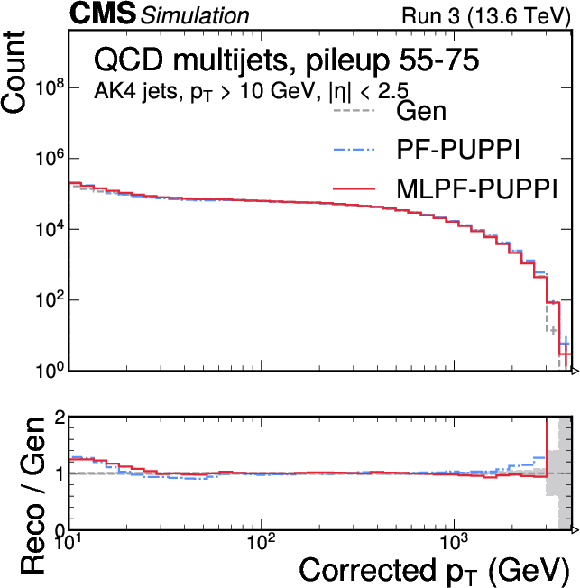

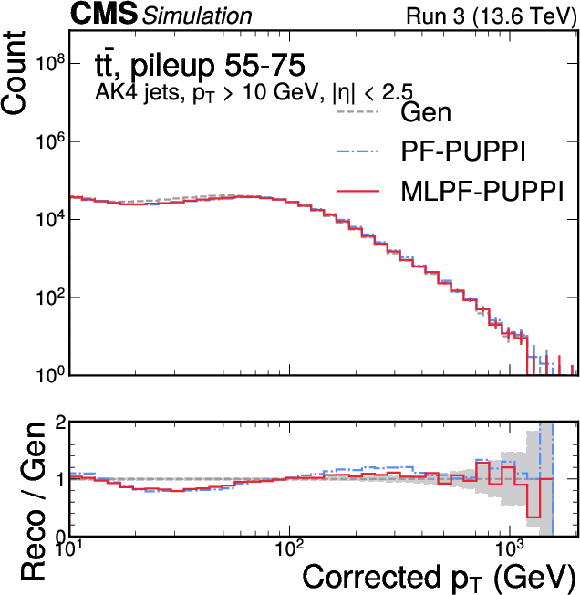

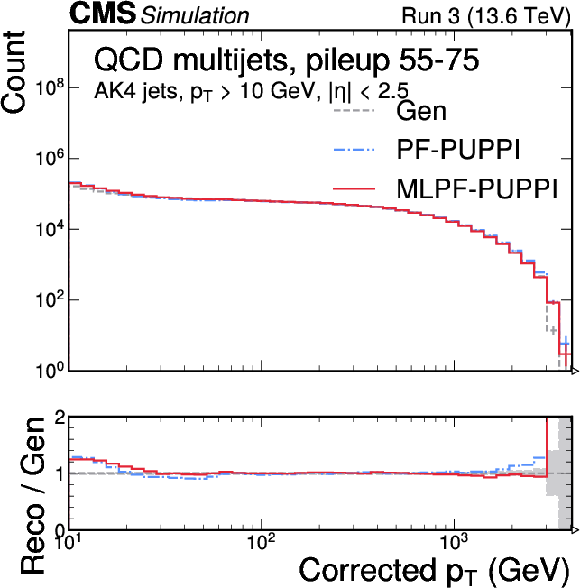

The corrected jet $ p_{\mathrm{T}} $ distribution in $ \mathrm{t} \overline{\mathrm{t}} $ (left) and QCD multijet (right) validation samples with 55--75 pileup interactions. MLPF is only trained to reconstruct particles, and is never explicitly optimized to reconstruct jets. The PUPPI algorithm is applied to both PF and MLPF jets to perform pileup subtraction. We show the jet $ p_{\mathrm{T}} $ distribution after simulated response calibration. The shaded bands indicate the statistical uncertainties on Gen. |

png pdf |

Figure 6-a:

The corrected jet $ p_{\mathrm{T}} $ distribution in $ \mathrm{t} \overline{\mathrm{t}} $ (left) and QCD multijet (right) validation samples with 55--75 pileup interactions. MLPF is only trained to reconstruct particles, and is never explicitly optimized to reconstruct jets. The PUPPI algorithm is applied to both PF and MLPF jets to perform pileup subtraction. We show the jet $ p_{\mathrm{T}} $ distribution after simulated response calibration. The shaded bands indicate the statistical uncertainties on Gen. |

png pdf |

Figure 6-b:

The corrected jet $ p_{\mathrm{T}} $ distribution in $ \mathrm{t} \overline{\mathrm{t}} $ (left) and QCD multijet (right) validation samples with 55--75 pileup interactions. MLPF is only trained to reconstruct particles, and is never explicitly optimized to reconstruct jets. The PUPPI algorithm is applied to both PF and MLPF jets to perform pileup subtraction. We show the jet $ p_{\mathrm{T}} $ distribution after simulated response calibration. The shaded bands indicate the statistical uncertainties on Gen. |

png pdf |

Figure 6-c:

The corrected jet $ p_{\mathrm{T}} $ distribution in $ \mathrm{t} \overline{\mathrm{t}} $ (left) and QCD multijet (right) validation samples with 55--75 pileup interactions. MLPF is only trained to reconstruct particles, and is never explicitly optimized to reconstruct jets. The PUPPI algorithm is applied to both PF and MLPF jets to perform pileup subtraction. We show the jet $ p_{\mathrm{T}} $ distribution after simulated response calibration. The shaded bands indicate the statistical uncertainties on Gen. |

png pdf |

Figure 6-d:

The corrected jet $ p_{\mathrm{T}} $ distribution in $ \mathrm{t} \overline{\mathrm{t}} $ (left) and QCD multijet (right) validation samples with 55--75 pileup interactions. MLPF is only trained to reconstruct particles, and is never explicitly optimized to reconstruct jets. The PUPPI algorithm is applied to both PF and MLPF jets to perform pileup subtraction. We show the jet $ p_{\mathrm{T}} $ distribution after simulated response calibration. The shaded bands indicate the statistical uncertainties on Gen. |

png pdf |

Figure 7:

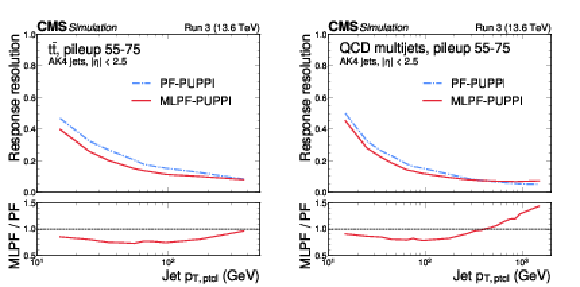

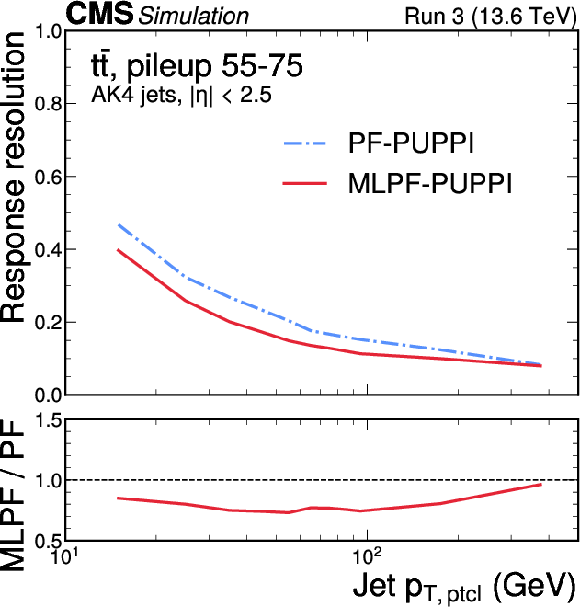

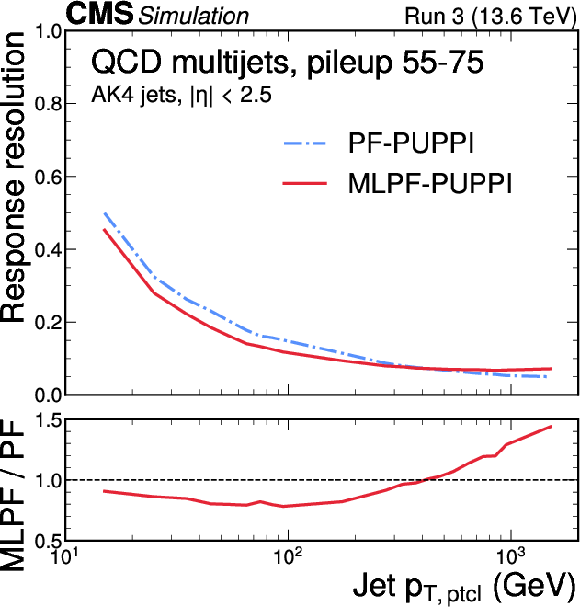

The jet resolution in $ \mathrm{t} \overline{\mathrm{t}} $ (left) and QCD multijet (right) validation samples with 55--75 pileup interactions, after simulated response calibration. The MLPF algorithm is only trained to reconstruct particles, and is never explicitly optimized to reconstruct jets. The PUPPI algorithm is applied to both PF and MLPF jets to perform pileup subtraction. The jet resolution is parameterized by fitting a Gaussian distribution and dividing the best-fit standard deviation by the mean, showing the bin midpoints on the horizontal axis. |

png pdf |

Figure 7-a:

The jet resolution in $ \mathrm{t} \overline{\mathrm{t}} $ (left) and QCD multijet (right) validation samples with 55--75 pileup interactions, after simulated response calibration. The MLPF algorithm is only trained to reconstruct particles, and is never explicitly optimized to reconstruct jets. The PUPPI algorithm is applied to both PF and MLPF jets to perform pileup subtraction. The jet resolution is parameterized by fitting a Gaussian distribution and dividing the best-fit standard deviation by the mean, showing the bin midpoints on the horizontal axis. |

png pdf |

Figure 7-b:

The jet resolution in $ \mathrm{t} \overline{\mathrm{t}} $ (left) and QCD multijet (right) validation samples with 55--75 pileup interactions, after simulated response calibration. The MLPF algorithm is only trained to reconstruct particles, and is never explicitly optimized to reconstruct jets. The PUPPI algorithm is applied to both PF and MLPF jets to perform pileup subtraction. The jet resolution is parameterized by fitting a Gaussian distribution and dividing the best-fit standard deviation by the mean, showing the bin midpoints on the horizontal axis. |

png pdf |

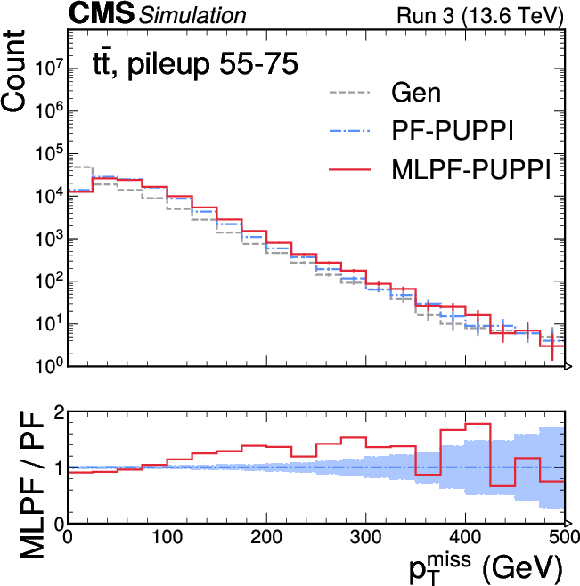

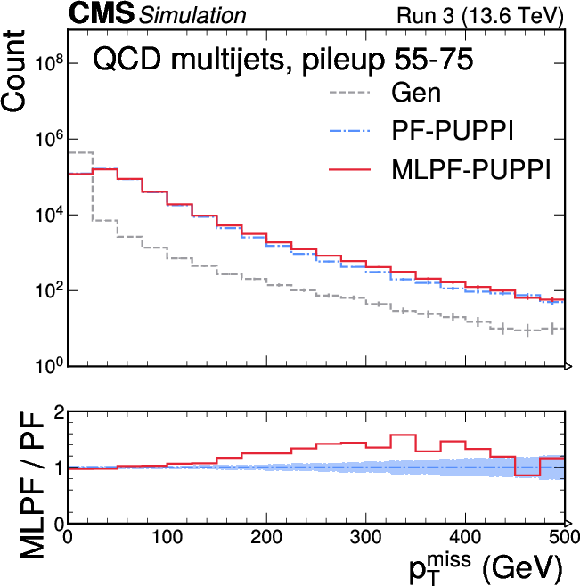

Figure 8:

Uncalibrated $ p_{\mathrm{T}}^\text{miss} $ in $ \mathrm{t} \overline{\mathrm{t}} $ (left) and QCD multijet (right) samples with pileup from offline reconstruction using PF and MLPF. The MLPF algorithm is only trained to reconstruct particles, and is never explicitly optimized to reconstruct $ p_{\mathrm{T}}^\text{miss} $. The $ p_{\mathrm{T}}^\text{miss} $ distributions from PF and MLPF are found to be generally consistent, with MLPF reconstructing a somewhat harder $ p_{\mathrm{T}}^\text{miss} $ spectrum in the tails. The vertical bars indicate the statistical uncertainties on the respective distributions, and the shaded bands in the ratio panel indicate the statistical uncertainties on PF. |

png pdf |

Figure 8-a:

Uncalibrated $ p_{\mathrm{T}}^\text{miss} $ in $ \mathrm{t} \overline{\mathrm{t}} $ (left) and QCD multijet (right) samples with pileup from offline reconstruction using PF and MLPF. The MLPF algorithm is only trained to reconstruct particles, and is never explicitly optimized to reconstruct $ p_{\mathrm{T}}^\text{miss} $. The $ p_{\mathrm{T}}^\text{miss} $ distributions from PF and MLPF are found to be generally consistent, with MLPF reconstructing a somewhat harder $ p_{\mathrm{T}}^\text{miss} $ spectrum in the tails. The vertical bars indicate the statistical uncertainties on the respective distributions, and the shaded bands in the ratio panel indicate the statistical uncertainties on PF. |

png pdf |

Figure 8-b:

Uncalibrated $ p_{\mathrm{T}}^\text{miss} $ in $ \mathrm{t} \overline{\mathrm{t}} $ (left) and QCD multijet (right) samples with pileup from offline reconstruction using PF and MLPF. The MLPF algorithm is only trained to reconstruct particles, and is never explicitly optimized to reconstruct $ p_{\mathrm{T}}^\text{miss} $. The $ p_{\mathrm{T}}^\text{miss} $ distributions from PF and MLPF are found to be generally consistent, with MLPF reconstructing a somewhat harder $ p_{\mathrm{T}}^\text{miss} $ spectrum in the tails. The vertical bars indicate the statistical uncertainties on the respective distributions, and the shaded bands in the ratio panel indicate the statistical uncertainties on PF. |

png pdf |

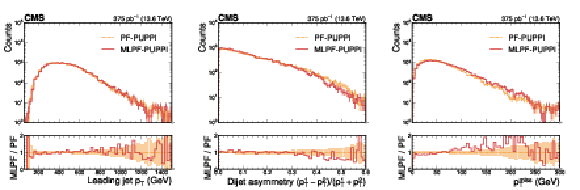

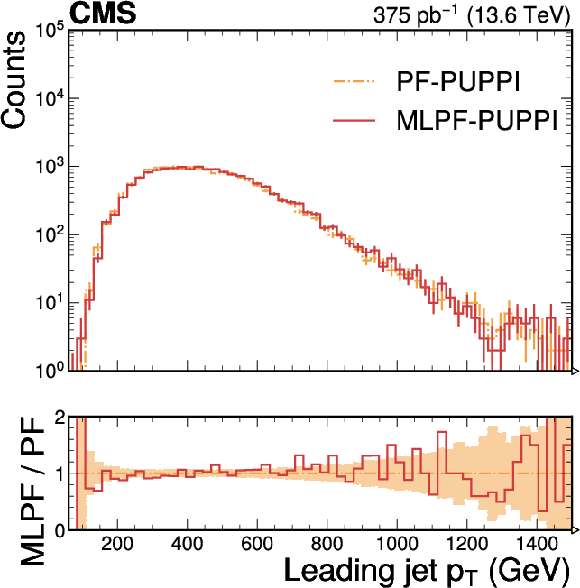

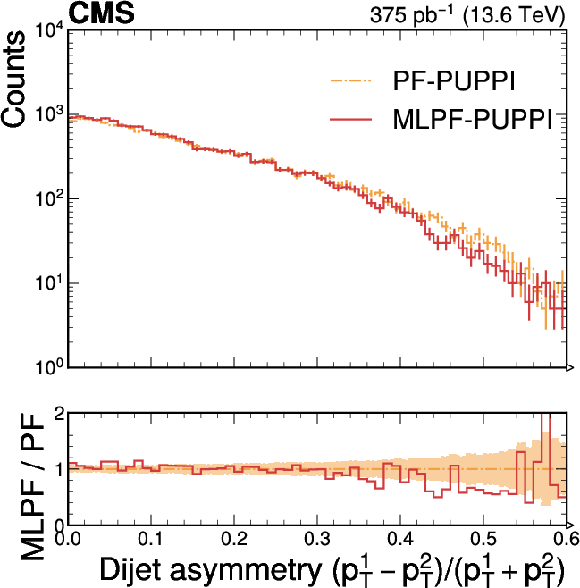

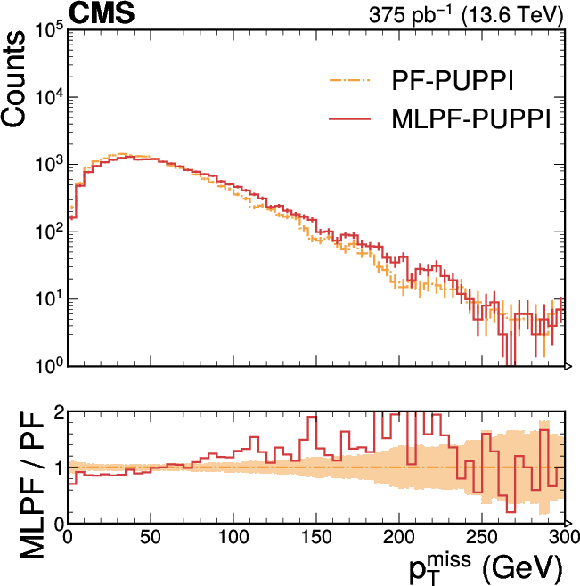

Figure 9:

Distributions of the leading jet $ p_{\text{T,corr}} $ (left), the dijet asymmetry (center), and $ p_{\mathrm{T}}^\text{miss} $ (right) in a small sample of dijet data collected in Run 3. The distributions are largely compatible. The vertical bars indicate the statistical uncertainties on the respective distributions, and the shaded bands in the ratio panel indicate the statistical uncertainties on PF. |

png pdf |

Figure 9-a:

Distributions of the leading jet $ p_{\text{T,corr}} $ (left), the dijet asymmetry (center), and $ p_{\mathrm{T}}^\text{miss} $ (right) in a small sample of dijet data collected in Run 3. The distributions are largely compatible. The vertical bars indicate the statistical uncertainties on the respective distributions, and the shaded bands in the ratio panel indicate the statistical uncertainties on PF. |

png pdf |

Figure 9-b:

Distributions of the leading jet $ p_{\text{T,corr}} $ (left), the dijet asymmetry (center), and $ p_{\mathrm{T}}^\text{miss} $ (right) in a small sample of dijet data collected in Run 3. The distributions are largely compatible. The vertical bars indicate the statistical uncertainties on the respective distributions, and the shaded bands in the ratio panel indicate the statistical uncertainties on PF. |

png pdf |

Figure 9-c:

Distributions of the leading jet $ p_{\text{T,corr}} $ (left), the dijet asymmetry (center), and $ p_{\mathrm{T}}^\text{miss} $ (right) in a small sample of dijet data collected in Run 3. The distributions are largely compatible. The vertical bars indicate the statistical uncertainties on the respective distributions, and the shaded bands in the ratio panel indicate the statistical uncertainties on PF. |

png pdf |

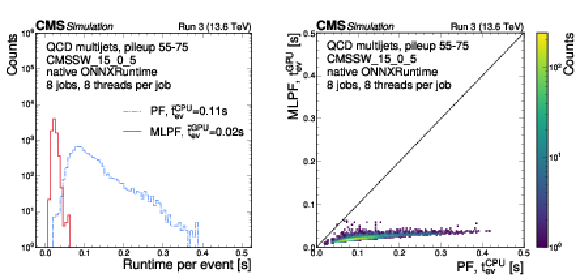

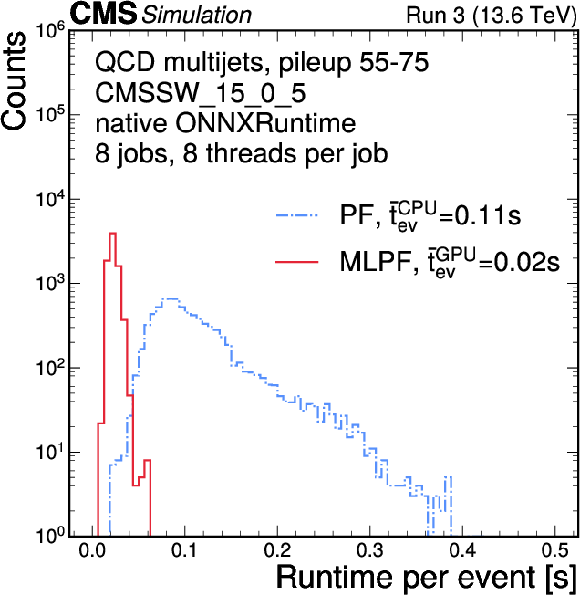

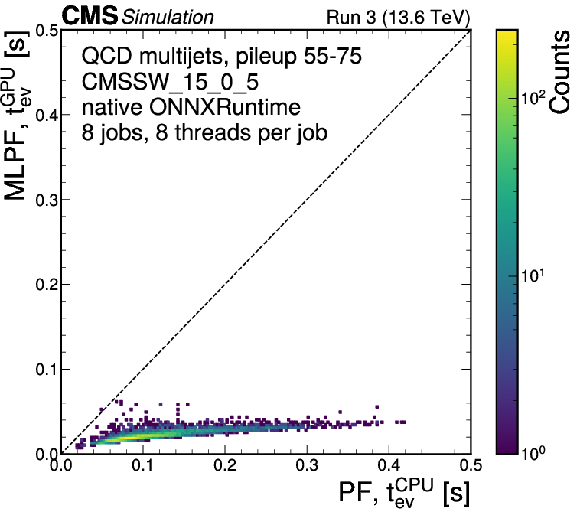

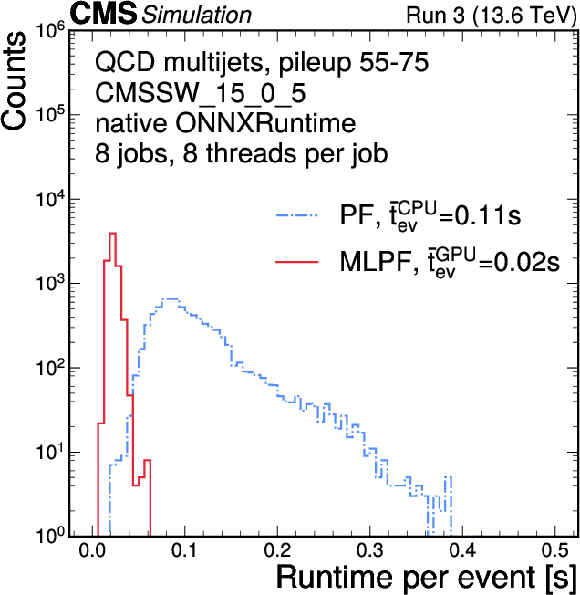

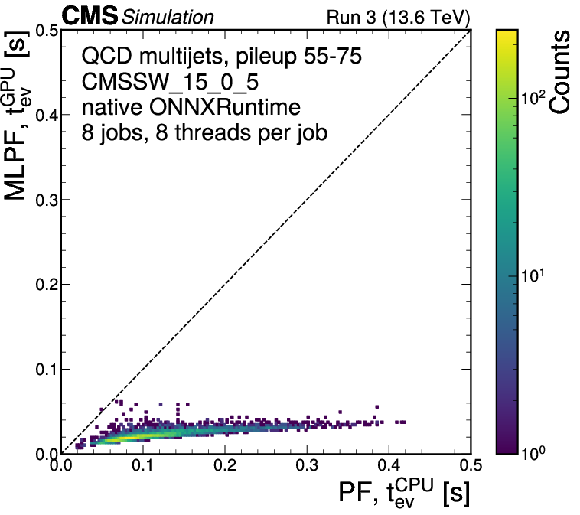

Figure 10:

The runtime of the baseline particle-flow reconstruction compared to the MLPF inference, directly within the CMS offline software using the native ONNXRUNTIME on GPU. |

png pdf |

Figure 10-a:

The runtime of the baseline particle-flow reconstruction compared to the MLPF inference, directly within the CMS offline software using the native ONNXRUNTIME on GPU. |

png pdf |

Figure 10-b:

The runtime of the baseline particle-flow reconstruction compared to the MLPF inference, directly within the CMS offline software using the native ONNXRUNTIME on GPU. |

png pdf |

Figure 10-c:

The runtime of the baseline particle-flow reconstruction compared to the MLPF inference, directly within the CMS offline software using the native ONNXRUNTIME on GPU. |

png pdf |

Figure 10-d:

The runtime of the baseline particle-flow reconstruction compared to the MLPF inference, directly within the CMS offline software using the native ONNXRUNTIME on GPU. |

| Tables | |

png pdf |

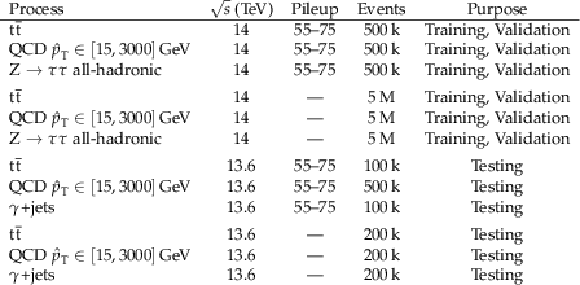

Table 1:

Monte Carlo simulation samples used for optimizing, validating, and testing the model. The training and validation samples are divided using an 80%/20% split, respectively. The symbols $ \text{---} $ in the 3rd column represent samples generated without pileup. |

| Summary |

| A machine-learning (ML)-based algorithm for particle-flow (PF) reconstruction in the CMS experiment has been presented. The algorithm correlates tracks and calorimeter clusters using successive transformer layers, and outputs a list of reconstructed particles with four-momenta and particle identification values. The algorithm is functionally equivalent to the standard PF algorithm currently used in CMS. The model is trained on CMS Run-3 (2023--2024) full simulation data sets that include realistic pileup conditions, and its performance is evaluated in simulated top quark-antiquark ( $ \mathrm{t} \overline{\mathrm{t}} $) and quantum chromodynamics multijet testing samples across different experimental conditions, as well as on data collected using a dijet trigger. To ensure computational efficiency, the model avoids quadratic scaling in runtime and memory by efficiently employing modern graphics processing units (GPUs). The ML-based PF (MLPF) algorithm achieves physics performance comparable to the standard PF algorithm, while enabling GPU acceleration for full event reconstruction within the CMS offline software framework. Specifically, we observe improved neutral hadron efficiency with MLPF while maintaining the same misidentification rate as standard PF. For jets with $ p_{\mathrm{T}} $ between 30--100 GeV in $ \mathrm{t} \overline{\mathrm{t}} $ events, we observe a 10--20% improvement in jet energy resolution compared to standard PF. The algorithm delivers a per-event runtime of approximately 20\unitms on an Nvidia L4 inference GPU, with 64 inference streams running in parallel per GPU. We also observe improved runtime scaling with event size compared to the standard PF algorithm, highlighting the computational robustness of the approach. While the MLPF algorithm has been successfully benchmarked under Run-3 conditions, its primary motivation lies in deployment at the high-luminosity upgrade of the LHC (HL-LHC), where the increased event complexity and pileup conditions demand both high physics performance and computational scalability. To deploy MLPF in production at the HL-LHC, several developments are foreseen. First, the model must be retrained for the upgraded detector and higher pileup conditions. Second, ensuring the portability of the inference across different GPU generations and hardware vendors is essential. Third, the model inference can be further optimized through techniques such as sparse or block attention, quantization, pruning, and asynchronous or batched execution. Finally, the physics performance and robustness can be improved through additional training and extensive cross-checks on a wide variety of simulated and data samples. |

| References | ||||

| 1 | CMS Collaboration | Particle-flow reconstruction and global event description with the CMS detector | JINST 12 (2017) P10003 | CMS-PRF-14-001 1706.04965 |

| 2 | ALEPH Collaboration | Performance of the ALEPH detector at LEP | NIM A 360 (1995) 481 | |

| 3 | ATLAS Collaboration | Jet reconstruction and performance using particle flow with the ATLAS detector | EPJC 77 (2017) 466 | 1703.10485 |

| 4 | A. Bocci, S. Lami, S. Kuhlmann, and G. Latino | Study of jet energy resolution at CDF | Int. J. Mod. Phys. A 16 (2001) 255 | |

| 5 | CDF Collaboration | A search for supersymmetric Higgs bosons in the di-tau decay mode in $ \mathrm{p}\overline{\mathrm{p}} $ collisions at 1.8 TeV | PRD 72 (2005) 112008 | hep-ex/0506042 |

| 6 | CDF Collaboration | Measurement of $ \sigma(\mathrm{p}\overline{\mathrm{p}} \to \mathrm{Z})\mathcal{B}(\mathrm{Z} \to \tau\tau) $ in $ \mathrm{p}\overline{\mathrm{p}} $ collisions at $ \sqrt{s}= $ 1.96 TeV | PRD 75 (2007) 092004 | |

| 7 | CELLO Collaboration | An analysis of the charged and neutral energy flow in $ \mathrm{e}^+\mathrm{e}^- $ hadronic annihilation at 34 GeV, and a determination of the QCD effective coupling constant | PLB 113 (1982) 427 | |

| 8 | D0 Collaboration | Measurement of $ \sigma(\mathrm{p}\overline{\mathrm{p}} \to \mathrm{Z} + \mathrm{X})\mathcal{B}(\mathrm{Z} \to \tau^+ \tau^-) $ at $ \sqrt{s} = $ 1.96 TeV | PLB 670 (2009) 292 | 0808.1306 |

| 9 | DELPHI Collaboration | Performance of the DELPHI detector | NIM A 378 (1996) 57 | |

| 10 | H1 Collaboration | Measurement of charged particle multiplicity distributions in DIS at HERA and its implication to entanglement entropy of partons | EPJC 81 (2021) 212 | 2011.01812 |

| 11 | ZEUS Collaboration | Measurement of the diffractive structure function $ F_2^{D(4)} $ at HERA | EPJC 1 (1998) 81 | hep-ex/9709021 |

| 12 | ZEUS Collaboration | Measurement of the diffractive cross-section in deep inelastic scattering using ZEUS 1994 data | EPJC 6 (1999) 43 | hep-ex/9807010 |

| 13 | FCC Collaboration | FCC-ee: The lepton collider. Future Circular Collider conceptual design report volume 2 | Eur. Phys. J. ST 228 (2019) 261 | |

| 14 | CMSnoop | The International Linear Collider technical design report - volume 1: executive summary | \hrefT. Behnke et al.,, 2013 | 1306.6327 |

| 15 | CEPC Study Group | CEPC conceptual design report: volume 2 - physics \& detector | 1811.10545 | |

| 16 | F. Mokhtar et al. | Fine-tuning machine-learned particle-flow reconstruction for new detector geometries in future colliders | PRD 111 (2025) 092015 | 2503.00131 |

| 17 | F. A. Di Bello et al. | Towards a computer vision particle flow | EPJC 81 (2021) 107 | 2003.08863 |

| 18 | J. Kieseler | Object condensation: one-stage grid-free multi-object reconstruction in physics detectors, graph and image data | EPJC 80 (2020) 886 | 2002.03605 |

| 19 | J. Shlomi, P. Battaglia, and J.-R. Vlimant | Graph neural networks in particle physics | Mach. Learn. Sci. Tech. 2 (2021) 021001 | 2007.13681 |

| 20 | J. Pata et al. | MLPF: Efficient machine-learned particle-flow reconstruction using graph neural networks | EPJC 81 (2021) 381 | 2101.08578 |

| 21 | CMS Collaboration | GNN-based end-to-end reconstruction in the CMS Phase 2 High-Granularity Calorimeter | J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2438 (2023) 012090 | 2203.01189 |

| 22 | CMS Collaboration | Machine learning for particle flow reconstruction at CMS | J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2438 (2023) 012100 | 2203.00330 |

| 23 | F. Mokhtar et al. | Progress towards an improved particle flow algorithm at CMS with machine learning | in st Int. Workshop on Advanced Computing and Analysis Techniques in Physics Research, 2023 Proc. 2 (2023) 1 |

2303.17657 |

| 24 | F. A. Di Bello et al. | Reconstructing particles in jets using set transformer and hypergraph prediction networks | EPJC 83 (2023) 596 | 2212.01328 |

| 25 | J. Pata et al. | Improved particle-flow event reconstruction with scalable neural networks for current and future particle detectors | Commun. Phys. 7 (2024) 124 | 2309.06782 |

| 26 | P. Wahlen and T. Suehara | Particle-flow reconstruction with transformer | Eur. Phys. J. Web Conf. 315 (2024) 03010 | |

| 27 | N. Kakati et al. | HGPflow: Extending hypergraph particle flow to collider event reconstruction | EPJC 85 (2025) 847 | 2410.23236 |

| 28 | D. Kobylianskii et al. | GLOW: A unified particle flow transformer | in Proc. 8th th Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, 2025 Machine Learning and the Physical Sciences Workshop at the 3 (2025) 9 |

2508.20092 |

| 29 | CMS Collaboration | Portable acceleration of CMS computing workflows with coprocessors as a service | Comput. Softw. Big Sci. 8 (2024) 17 | CMS-MLG-23-001 2402.15366 |

| 30 | I. Bejar Alonso et al. | High-Luminosity Large Hadron Collider (HL-LHC): technical design report | CERN Yellow Rep. Monogr. 10 (2020) | |

| 31 | T. Dorigo et al. | Toward the end-to-end optimization of particle physics instruments with differentiable programming | Rev. Phys. 10 (2023) 100085 | 2203.13818 |

| 32 | M. Aehle et al. | Progress in end-to-end optimization of fundamental physics experimental apparata with differentiable programming | Rev. Phys. 13 (2025) 100120 | 2310.05673 |

| 33 | CMS Collaboration | High-precision measurement of the W boson mass with the CMS experiment at the LHC | Accepted by \emphNature, 2024 | CMS-SMP-23-002 2412.13872 |

| 34 | H. Qu and L. Gouskos | Jet tagging via particle clouds | PRD 101 (2020) 056019 | 1902.08570 |

| 35 | H. Qu, C. Li, and S. Qian | Particle transformer for jet tagging | in th Int. Conference on Machine Learning, volume 162, 2022 Proc. 3 (2022) 18281 |

2202.03772 |

| 36 | E. A. Moreno et al. | JEDI-net: a jet identification algorithm based on interaction networks | EPJC 80 (2020) 58 | 1908.05318 |

| 37 | E. A. Moreno et al. | Interaction networks for the identification of boosted $ \mathrm{H} \to \mathrm{b}\overline{\mathrm{b}} $ decays | PRD 102 (2020) 012010 | 1909.12285 |

| 38 | V. Mikuni and F. Canelli | ABCNet: An attention-based method for particle tagging | Eur. Phys. J. Plus 135 (2020) 463 | 2001.05311 |

| 39 | S. Farrell et al. | Novel deep learning methods for track reconstruction | in Proc. 4th Int. Workshop Connecting the Dots, 2018 | 1810.06111 |

| 40 | X. Ju et al. | Graph neural networks for particle reconstruction in high energy physics detectors | in Proc. 2nd rd Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, 2020 Machine Learning and the Physical Sciences Workshop at the 3 (2020) 3 |

2003.11603 |

| 41 | S. Amrouche et al. | The tracking machine learning challenge: Accuracy phase | in The NeurIPS '18 Competition, 2020 link |

1904.06778 |

| 42 | S. Amrouche et al. | Similarity hashing for charged particle tracking | in, 2019 Proc. IEEE International Conference on Big Data 201 (2019) 1595 |

|

| 43 | N. Choma et al. | Track seeding and labelling with embedded-space graph neural networks | in Proc. 6th Int. Workshop Connecting the Dots. 202 (1900) 0 |

2007.00149 |

| 44 | G. DeZoort et al. | Charged particle tracking via edge-classifying interaction networks | Comput. Softw. Big Sci. 5 (2021) 26 | 2103.16701 |

| 45 | S. Van Stroud et al. | Transformers for charged particle track reconstruction in high energy physics | 2411.07149 | |

| 46 | S. Farrell et al. | The HEP.TrkX Project: Deep neural networks for HL-LHC online and offline tracking | in Eur. Phys. J. Web Conf., volume 150, 2017 link |

|

| 47 | X. Ju et al. | Performance of a geometric deep learning pipeline for HL-LHC particle tracking | EPJC 81 (2021) 876 | 2103.06995 |

| 48 | S. Miao et al. | Locality-sensitive hashing-based efficient point transformer with applications in high-energy physics | in st Int. Conference on Machine Learning, volume 235, 2024 Proc. 4 (2024) 35546 |

2402.12535 |

| 49 | J. Shlomi et al. | Secondary vertex finding in jets with neural networks | EPJC 81 (2021) 540 | 2008.02831 |

| 50 | S. Van Stroud et al. | Secondary vertex reconstruction with MaskFormers | EPJC 84 (2024) 1020 | 2312.12272 |

| 51 | X. Ju and B. Nachman | Supervised jet clustering with graph neural networks for Lorentz boosted bosons | PRD 102 (2020) 075014 | 2008.06064 |

| 52 | J. Li, T. Li, and F.-Z. Xu | Reconstructing boosted Higgs jets from event image segmentation | JHEP 04 (2021) 156 | 2008.13529 |

| 53 | J. Guo, J. Li, T. Li, and R. Zhang | Boosted Higgs boson jet reconstruction via a graph neural network | PRD 103 (2021) 116025 | 2010.05464 |

| 54 | M. J. Fenton et al. | Permutationless many-jet event reconstruction with symmetry preserving attention networks | PRD 105 (2022) 112008 | 2010.09206 |

| 55 | A. Shmakov et al. | SPANet: Generalized permutationless set assignment for particle physics using symmetry preserving attention | SciPost Phys. 12 (2022) 178 | 2106.03898 |

| 56 | M. J. Fenton et al. | Reconstruction of unstable heavy particles using deep symmetry-preserving attention networks | Commun. Phys. 7 (2024) 139 | 2309.01886 |

| 57 | H. Li et al. | Reconstruction of boosted and resolved multi-Higgs-boson events with symmetry-preserving attention networks | JHEP 11 (2025) 119 | 2412.03819 |

| 58 | S. R. Qasim, J. Kieseler, Y. Iiyama, and M. Pierini | Learning representations of irregular particle-detector geometry with distance-weighted graph networks | EPJC 79 (2019) 608 | 1902.07987 |

| 59 | P. T. Komiske, E. M. Metodiev, B. Nachman, and M. D. Schwartz | Pileup mitigation with machine learning (PUMML) | JHEP 12 (2017) 051 | 1707.08600 |

| 60 | J. Arjona Mart \'\i nez et al. | Pileup mitigation at the Large Hadron Collider with graph neural networks | Eur. Phys. J. Plus 134 (2019) 333 | 1810.07988 |

| 61 | T. Li et al. | Semi-supervised graph neural networks for pileup noise removal | EPJC 83 (2023) 99 | 2203.15823 |

| 62 | CMS Collaboration | The phase-2 upgrade of the CMS tracker | CMS Technical Design Report CERN-LHCC-2017-009, CMS-TDR-014, 2017 link |

|

| 63 | CMS Collaboration | A MIP timing detector for the CMS phase-2 upgrade | CMS Technical Design Report CERN-LHCC-2019-003, CMS-TDR-020, 2019 CDS |

|

| 64 | CMS Collaboration | The phase-2 upgrade of the CMS level-1 trigger | CMS Technical Design Report CERN-LHCC-2020-004, CMS-TDR-021, 2020 CDS |

|

| 65 | CMS Collaboration | The phase-2 upgrade of the CMS data acquisition and high level trigger | CMS Technical Design Report CERN-LHCC-2021-007, CMS-TDR-022, 2020 CDS |

|

| 66 | CMS Collaboration | The phase-2 upgrade of the CMS beam radiation instrumentation and luminosity detectors | CMS Technical Design Report CERN-LHCC-2021-008, CMS-TDR-023, 2021 CDS |

|

| 67 | CMS Collaboration | The phase-2 upgrade of the CMS barrel calorimeters | CMS Technical Design Report CERN-LHCC-2017-011, CMS-TDR-015, 2017 CDS |

|

| 68 | CMS Collaboration | The phase-2 upgrade of the CMS endcap calorimeter | CMS Technical Design Report CERN-LHCC-2017-023, CMS-TDR-019, 2017 CDS |

|

| 69 | CMS Collaboration | The phase-2 upgrade of the CMS muon detectors | CMS Technical Design Report CERN-LHCC-2017-012, CMS-TDR-016, 2017 CDS |

|

| 70 | CMS Collaboration | The CMS experiment at the CERN LHC | JINST 3 (2008) S08004 | |

| 71 | CMS Collaboration | Development of the CMS detector for the CERN LHC Run 3 | JINST 19 (2024) P05064 | CMS-PRF-21-001 2309.05466 |

| 72 | CMS Collaboration | Performance of the CMS Level-1 trigger in proton-proton collisions at $ \sqrt{s} = $ 13 TeV | JINST 15 (2020) P10017 | CMS-TRG-17-001 2006.10165 |

| 73 | CMS Collaboration | The CMS trigger system | JINST 12 (2017) P01020 | CMS-TRG-12-001 1609.02366 |

| 74 | CMS Collaboration | Performance of the CMS high-level trigger during LHC Run 2 | JINST 19 (2024) P11021 | CMS-TRG-19-001 2410.17038 |

| 75 | CMS Collaboration | Electron and photon reconstruction and identification with the CMS experiment at the CERN LHC | JINST 16 (2021) P05014 | CMS-EGM-17-001 2012.06888 |

| 76 | CMS Collaboration | Performance of the CMS muon detector and muon reconstruction with proton-proton collisions at $ \sqrt{s}= $ 13 TeV | JINST 13 (2018) P06015 | CMS-MUO-16-001 1804.04528 |

| 77 | CMS Collaboration | Description and performance of track and primary-vertex reconstruction with the CMS tracker | JINST 9 (2014) P10009 | CMS-TRK-11-001 1405.6569 |

| 78 | P. Billoir and S. Qian | Simultaneous pattern recognition and track fitting by the kalman filtering method | NIM A 294 (1990) 219 | |

| 79 | CMS Collaboration | Heterogeneous reconstruction of hadronic particle flow clusters with the Alpaka portability library | Eur. Phys. J. Web Conf. 337 (2025) 01171 | |

| 80 | M. Cacciari, G. P. Salam, and G. Soyez | The anti-$ k_{\mathrm{T}} $ jet clustering algorithm | JHEP 04 (2008) 063 | 0802.1189 |

| 81 | M. Cacciari, G. P. Salam, and G. Soyez | FastJet | EPJC 72 (2012) 1896 | 1111.6097 |

| 82 | CMS Collaboration | Jet energy scale and resolution in the CMS experiment in pp collisions at 8 TeV | JINST 12 (2017) P02014 | CMS-JME-13-004 1607.03663 |

| 83 | CMS Collaboration | Pileup mitigation at CMS in 13 TeV data | JINST 15 (2020) P09018 | CMS-JME-18-001 2003.00503 |

| 84 | D. Bertolini, P. Harris, M. Low, and N. Tran | Pileup per particle identification | JHEP 10 (2014) 059 | 1407.6013 |

| 85 | CMS Collaboration | Technical proposal for the Phase-II upgrade of the Compact Muon Solenoid | CMS Technical Proposal CERN-LHCC-2015-010, CMS-TDR-15-02, 2015 CDS |

|

| 86 | CMS Collaboration | Performance of missing transverse momentum reconstruction in proton-proton collisions at $ \sqrt{s} = $ 13 TeV using the CMS detector | JINST 14 (2019) P07004 | CMS-JME-17-001 1903.06078 |

| 87 | C. Bierlich et al. | A comprehensive guide to the physics and usage of PYTHIA8.3 | SciPost Phys. Codeb, 2022 link |

2203.11601 |

| 88 | CMS Collaboration | Extraction and validation of a new set of CMS PYTHIA8 tunes from underlying-event measurements | EPJC 80 (2020) 4 | CMS-GEN-17-001 1903.12179 |

| 89 | GEANT4 Collaboration | GEANT 4---a simulation toolkit | NIM A 506 (2003) 250 | |

| 90 | GEANT4 Collaboration | GEANT 4 developments and applications | IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 53 (2006) 270 | |

| 91 | GEANT4 Collaboration | Recent developments in GEANT 4 | NIM A 835 (2016) 186 | |

| 92 | A. Vaswani et al. | Attention is all you need | in Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, I. Guyon et al., eds., volume 30, Curran Associates, Inc, 2017 link |

1706.03762 |

| 93 | T.-Y. Lin et al. | Focal loss for dense object detection | IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 42 (2020) 318 | 1708.02002 |

| 94 | D. Holmberg | Jet energy corrections with graph neural network regression | PhD thesis, Master's thesis, University of Helsinki, 2022 link |

|

| 95 | T. Dao et al. | FLASHATTENTION: Fast and memory-efficient exact attention with IO-awareness | in Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, S. Koyejo et al., eds., volume 35, Curran Associates, Inc, 2022 link |

2205.14135 |

| 96 | R. Xiong et al. | On layer normalization in the transformer architecture | in Int. Conference on Machine Learning, H. Daumé III and A. Singh, eds., volume 119, PMLR, 1052 Xiong in Proc. 3 (1052) 4 |

2002.04745 |

| 97 | J. Pata et al. | jpata/particleflow: v2.5.0 | link | |

| 98 | A. Paszke et al. | PYTORCH: An imperative style, high-performance deep learning library | in Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, H. Wallach et al., eds., volume 32, Curran Associates, Inc, 2019 link |

1912.01703 |

| 99 | CMS Collaboration | A unified approach for jet tagging in Run 3 at $ \sqrt{s}= $ 13.6 TeV in CMS | CMS Detector Performance Note CMS-DP-2024-066, 2024 CDS |

|

| 100 | CMS Collaboration | Flavour tagging performance of the updated unified particle transformer algorithm with the CMS experiment at $ \sqrt{s}= $ 13.6 TeV | CMS Detector Performance Note CMS-DP-2025-081, 2025 CDS |

|

| 101 | CMS Collaboration | Jet energy scale and resolution of jets with ParticleNet $ p_{\mathrm{T}} $ regression using Run 3 data collected by the CMS experiment in 2022 and 2023 at 13.6 TeV | CMS Detector Performance Note CMS-DP-2024-064, 2024 CDS |

|

| 102 | CMS Collaboration | DeepMET: Improving missing transverse momentum estimation with a deep neural network | Submitted to Phys. Rev. D, 2025 | CMS-JME-24-001 2509.12012 |

| 103 | CMS Collaboration | Jet algorithms performance in 13 TeV data | CMS Physics Analysis Summary, 2017 CMS-PAS-JME-16-003 |

CMS-PAS-JME-16-003 |

| 104 | CMS Collaboration | Open neural network exchange ( ONNX ) | \href{ONNX}\url{https://github.com/onnx/onnx. Accessed: -11-02, 2025} | |

|

Compact Muon Solenoid LHC, CERN |

|

|

|

|

|

|