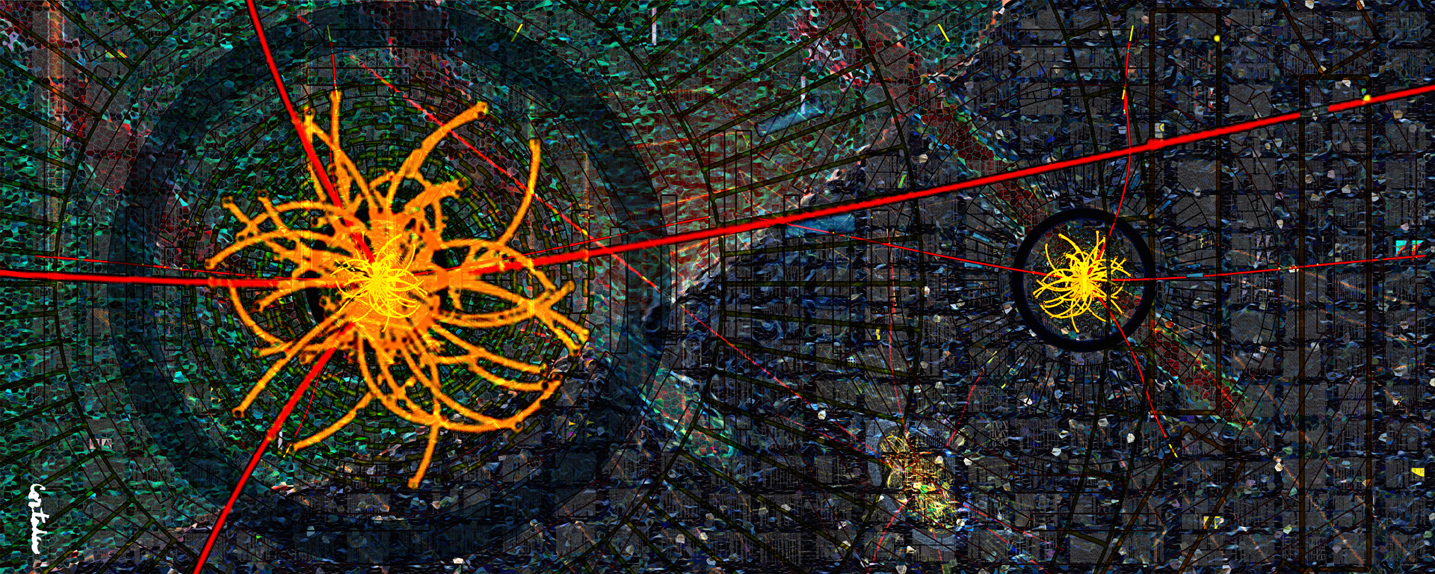

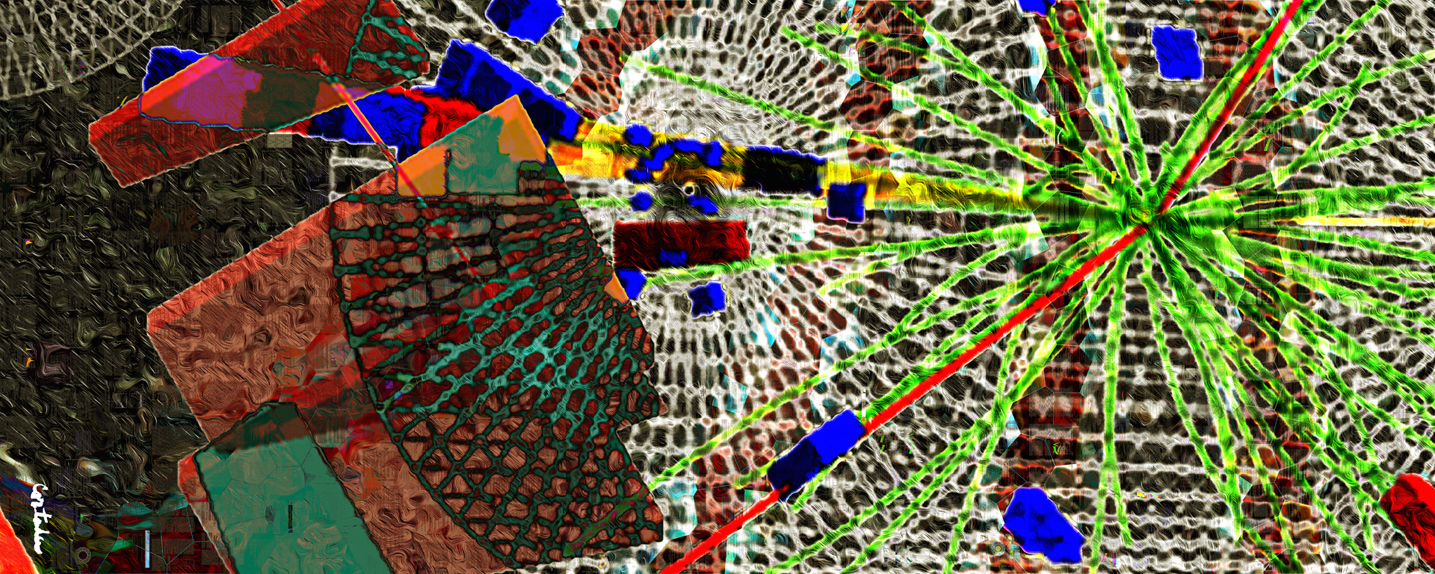

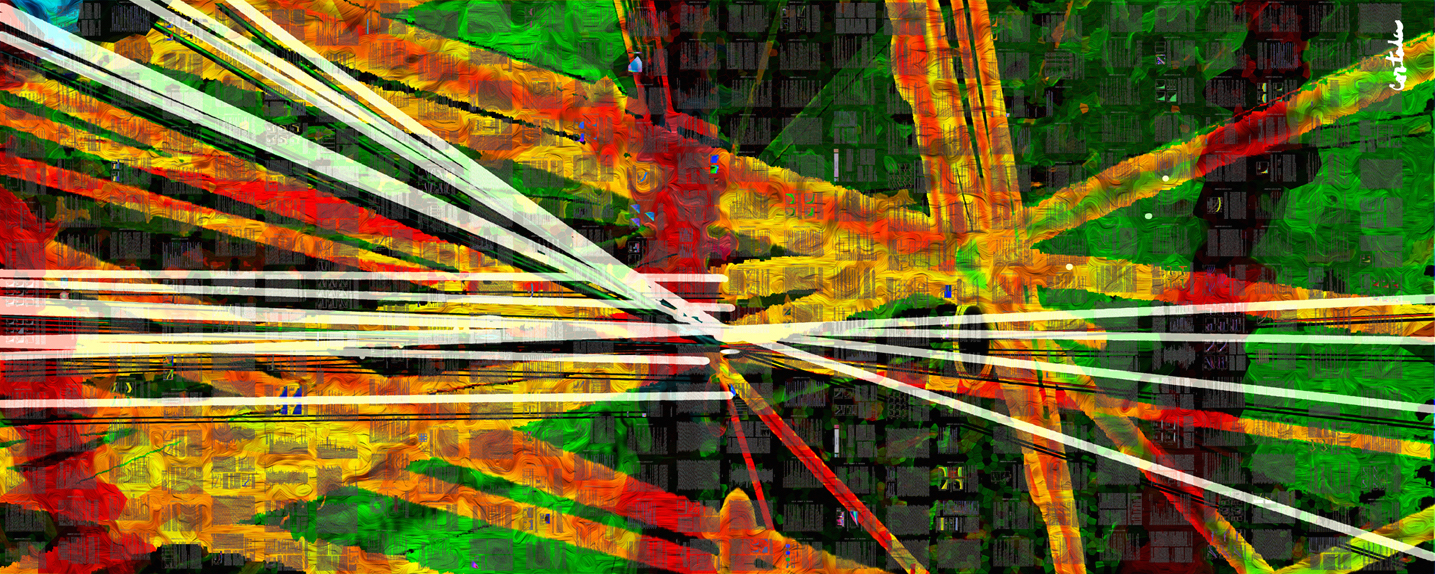

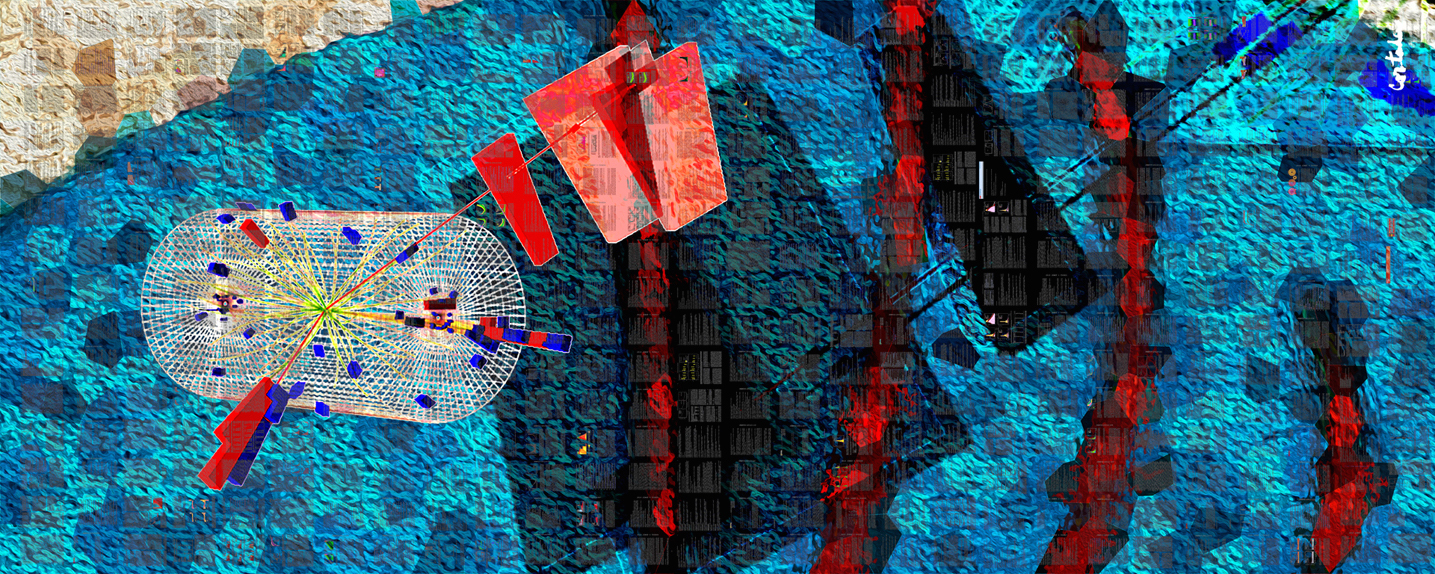

Compact Muon Solenoid

LHC, CERN

| CMS-PAS-MLG-23-002 | ||

| Machine-learning techniques for model-independent searches in dijet final states | ||

| CMS Collaboration | ||

| 2025-07-12 | ||

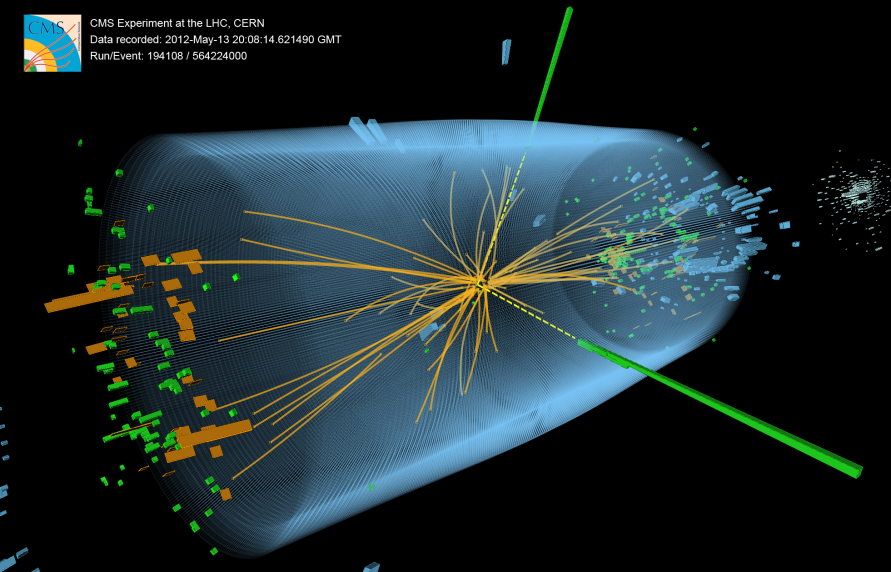

| Abstract: Anomaly detection methods used in a recent search for new phenomena at the CMS Experiment at the LHC are presented. The methods use machine learning to detect anomalous jets produced in the decay of new massive particles. The effectiveness of these approaches in enhancing sensitivity to various signals is studied and compared using data collected in proton-proton collisions at a center-of-mass energy of 13 TeV and amounting to 138 fb$ ^{-1} $. In addition, the capabilities of anomaly detection methods are illustrated by identifying boosted jets corresponding to hadronically decaying top quarks in a model-agnostic fashion. | ||

|

Links:

CDS record (PDF) ;

CADI line (restricted) ;

These preliminary results are superseded in this paper, Submitted to MLST. The superseded preliminary plots can be found here. |

||

|

Compact Muon Solenoid LHC, CERN |

|

|

|

|

|

|